Some 30 students, teachers, and activists emerged from the bus carrying boxes of books. As they stepped onto the pavement Saturday and into the bright Tucson sun, they chanted in unison, “What do we want? Books! When do we want them? Now! Who are we? Librostraficantes!”

The Spanish term, which means “book smugglers,” is the brainchild of Houston Community College professor and author Tony Diaz, who with a few dozen supporters set out March 12 for Arizona to protest a 2010 state law that prohibits certain types of ethnic studies in public schools. In January officials shut down the Tucson Unified School District’s Mexican-American-studies curriculum. The Librotraficante Caravan traveled through Texas and New Mexico, stopping in cities along the way to hold literary readings, collect donated books, and establish “underground libraries” filled with titles from Tucson’s banned courses. Several authors whose works were discontinued participated—Rudolfo Anaya, widely considered the godfather of Latino literature in the Southwest, even invited the caravan into his Albuquerque home for posole, traditional pork stew.

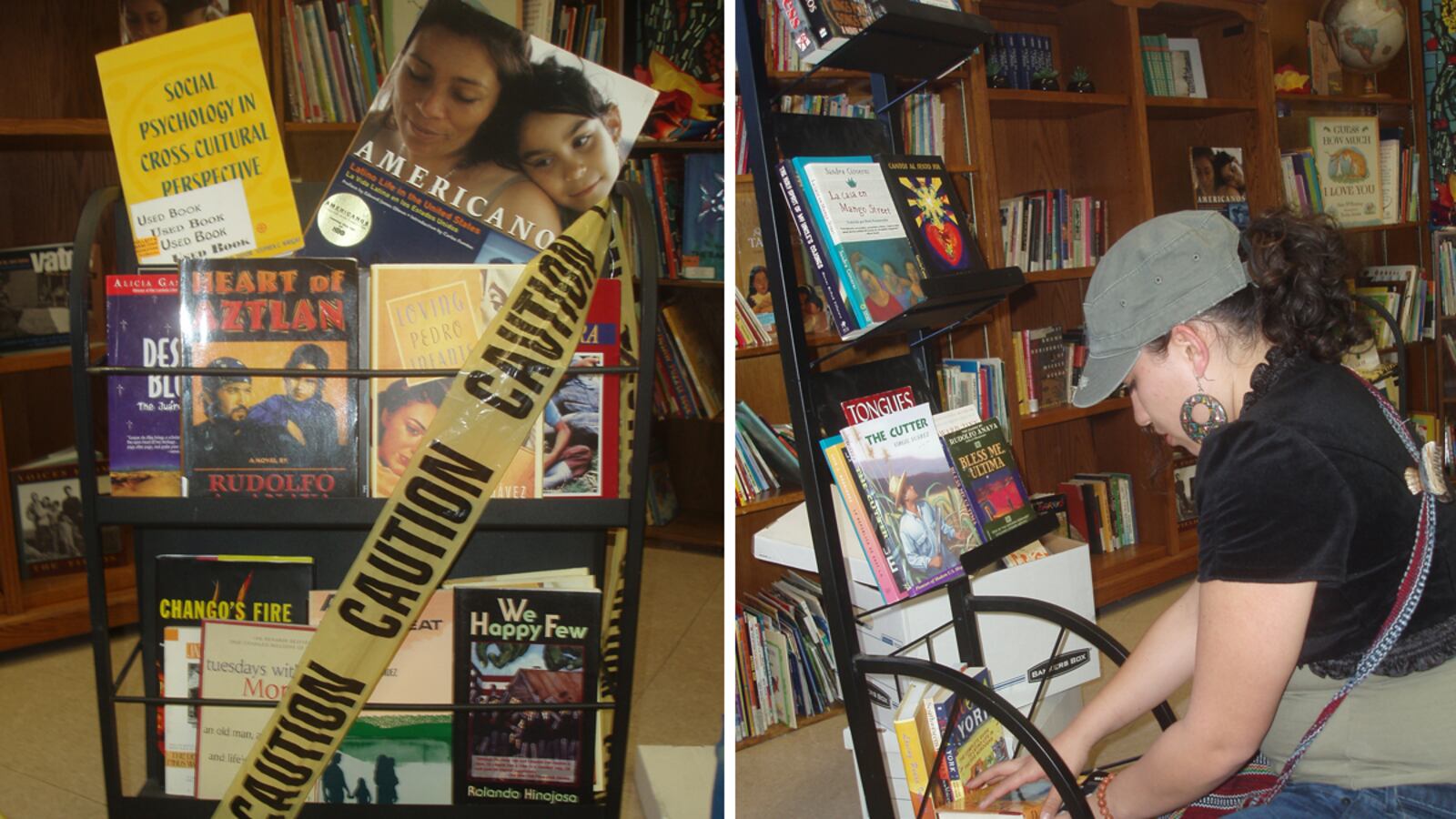

“I’m much obliged to the Tucson Unified School District for creating this little book club,” Diaz said after arriving at a youth center that will be the site of Tucson’s “underground library,” home to copies of some 80 books taught in the now-defunct program, including The House on Mango Street by bestselling author Sandra Cisneros, Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years, and The Devil’s Highway by Luis Alberto Urrea. “When Arizona legislators decided to erase our history, we decided to make more!”

The law originated amid Arizona’s heated debates over the immigration crackdown spearheaded by Republican legislators, Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, and Gov. Jan Brewer. The governor signed the ethnic-studies measure in May 2010, just weeks after signing into law the country’s toughest immigration bill in generations. (That measure, S.B. 1070, is heading to the Supreme Court in April.) Soon after, officials declared the Tucson program illegal, and a group of teachers sued the state in federal court. In January an administrative judge approved the courses’ elimination, and the classes’ books were boxed up and taken to storage facilities and school libraries. A district-court judge is scheduled to hear motions in the case today.

Arizona Attorney General Tom Horne wrote the ethnic-studies law while he was the state’s superintendent of public instruction. Banning courses that promote the overthrow of the U.S. government, encourage resentment against a group of people, or are created specifically for one group, the law was aimed squarely at the Tucson Mexican-American-studies program. Its teachers, Horne claims, taught Chicano history and literature through a racist and politicized filter that wrongly informed students that they’re oppressed by white people. (He says he began looking into the program in 2007 after labor leader Dolores Huerta told Tucson students that Republicans hated Latinos, and when he sent a Latina Republican aide to the school to counter that view, some students turned their backs and raised their fists in the air.)

“It’s a fundamental American value that what matters about us is what we know, what we can do, and what is our character—and that what race we were born into is irrelevant,” Horne says. “This program is teaching students the opposite—that what matters about people is their race.” In a recent court brief, he cites former district teachers who claim students became resentful and mistrustful of authorities after taking the classes, as well as a white student who said Hispanic students ceased speaking to her because of her race.

The program’s teachers and many of its students dismiss such accusations. Alfonso Chavez, 20, says the classes helped him understand his culture and history while getting an education that included the state-mandated core curriculum. “These classes are very relevant, especially here in the Southwest,” he said at a Librotraficante breakfast hosted by a Tucson gallery. “It helped me grow as a person, and my grades started improving.”

Erin Cain-Hodge, a 19-year-old University of Arizona student, says being one of three white pupils in one of the now prohibited courses was valuable. “I took the classes because I was constantly hearing from the same white male authors,” she says. “I thought, ‘There has to be more.’” Horne says the state’s standard courses include Chicano authors and even instances of historical oppression, but Mexican-American-studies supporters say Latino history and literature are underrepresented.

“Many of my students would come in and say they’d never read any Chicano literature before,” said Curtis Acosta, a plaintiff in the case who has taught in the Tucson schools since 2003. In a district that’s more than 60 percent Latino, teaching Chicano history and literature is crucial for students’ sense of belonging and academic development, he said. As for claims that he taught students to resent white people? “I think Horne needs to take credit for his own work,” Acosta said. “If he feels that anger, we definitely didn’t have to teach it, because he’s teaching it to them.”

The immigration debate was front and center at Anaya’s Albuquerque home last Friday. In his adobe house overlooking the Rio Grande, the acclaimed author of Bless Me, Ultima and Tortuga sat in his dining room with Diaz and Dagoberto Gilb, an award-winning Texas author whose book Woodcuts of Women was in the banished curriculum. Anaya recalled that decades ago certain New Mexico schools banned Bless Me, Ultima, whose protagonist is a curandera, or healer. (The bans were eventually overturned.) “It’s even worse now, because the political ideology is more extreme,” Anaya said. “It’s dangerous for our community—we’re the scapegoats for all of the country’s problems.”

The authors joked that you haven’t succeeded as a writer until your books have been banned, but the overall tone was serious. “This isn’t about ethnic studies, it’s about the anti-immigrant fervor in this country, and in Arizona in particular,” Gilb said. “You meet Mexican-American kids who don’t even know their literature, their history—in that respect I’m grateful to Tucson for opening this up so we can talk about it.”

The next morning the Librotraficantes filed back onto the bus and into a few cars, their collection of books now totaling more than 500. Their ranks included members of Nuestra Palabra, a Houston group that promotes youth literacy and Latino authors; a Mexican-American-studies teacher and school board member from Baytown, Texas; and a handful of college students.

Zelene Pineda, a 23-year-old poet and first-generation Mexican immigrant who says the work of bestselling author Cisneros inspired her to write and live authentically, was active in the 2006 student Mega Marchas in support of comprehensive immigration reform and now works at the New York Immigration Coalition. She traveled to Houston to be part of the weeklong journey and share her poems at readings along the way. Antonio Maldonado, 33, said that after enduring epithets like “coconut” and “gabacho” while growing up half white and half Mexican, Chicano studies helped him accept himself. “It didn’t make me racist or anti–white people,” he said on the bus, “it just made me embrace my heritage and culture and be proud of who I was.”

In Tucson, after a press conference and breakfast with local students and teachers, the Librotraficantes separated donated books to be sent to the “underground libraries” at nonprofits in San Antonio, Albuquerque, Houston, and Tucson. That evening, they would hold a banned-book bash, featuring readings from authors such as Pulitzer finalist Luis Alberto Urrea.

Horne, the attorney general, has taken pains to point out that the books on the curriculum were not actually banned, and that more than 100 copies are available at school libraries. But for those converging on Tucson over the weekend, the events were about more than what happened to the books after they were taken off class reading lists and removed from classrooms. For Luis Zamarripa, 21, a University of New Mexico student, it’s about taking action to protect something he believes in. “First Arizona passed S.B. 1070, and I was really upset about it,” he said outside the bus. “And now this—I felt I needed to get involved.”