As you enter the exhibition space at New York City’s Museum of Sex, you’re immediately aware of a pungent odor.

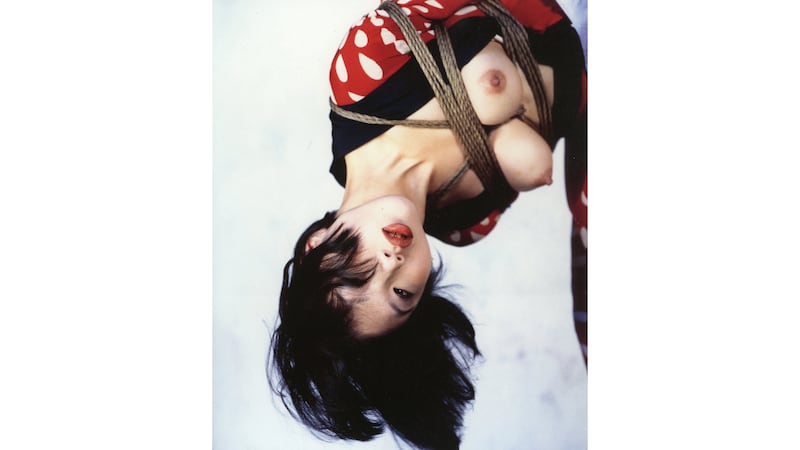

The smell comes from multiple pieces of hemp rope intricately lining the walls of a dark hallway, hinting at what is to come. At the end of the hemp jungle you are greeted by a large photograph of a woman, completely naked with the exception of a kimono dangling from behind.

The obscene, yet strange photo comes from Nobuyoshi Araki, infamously known as being Japan’s most controversial photographer, and this is the opening picture in the Museum of Sex’s retrospective devoted to him, The Incomplete Araki: Sex, Life, and Death in the Work of Nobuyoshi Araki,

In the picture, the woman is suspended in the air by rope which is tied behind her thighs, across her chest, and around her breasts. A flower delicately sits in front of her vagina, while a toy dinosaur adjacent to the model stomps away on the ground.

Often referring to his camera as a kamara (mara being a Japanese slang term for penis), Araki “has been labelled a pervert, a madman and a genius,” according to some text at the entrance of the exhibit.

The retrospective consists of hundreds of explicit photographs, and spans several decades. The exhibit was co-curated by Maggie Mustard, a Riggio fellow in art history and an expert on post-war Japanese photography, and Mark Snyder, the director of exhibitions at the Museum of Sex.

Nobuyoshi Araki, 2007 Sumi Ink on Black and White Photograph

Courtesy of Yoshii Gallery, New York“His photos are really shocking, especially his most explicit work that incorporates bondage,” Mustard told The Daily Beast. “It’s these photos that really push up against the boundaries of acceptability within Japanese legal and social society, as well as our own in society in the West.”

Having published over 500 photobooks since the start of career during the 1970s, many of Araki’s photos have been criticized in Japan and abroad. Due to obscenity laws in Japan that censor genitals or pubic hair, Araki’s work has been often confiscated by Japanese authorities. In the West, the photos were viewed as extremely sexist, but were never legally seized.

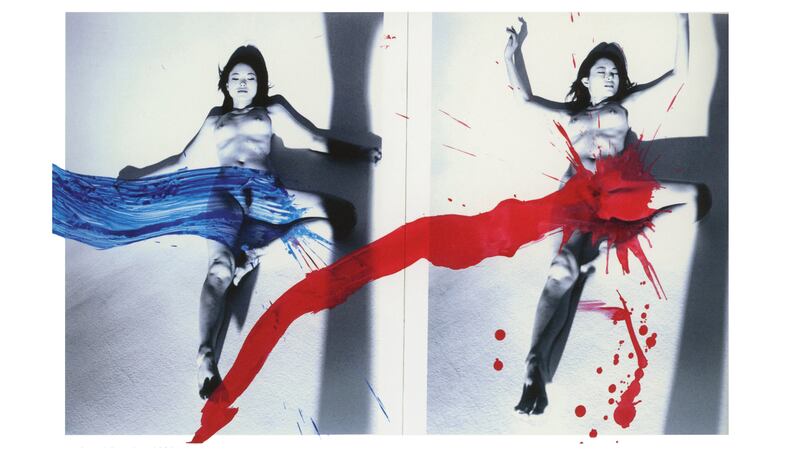

Nobuyoshi Araki, 2007 Acrylic paint on two B & W prints

Courtesy of Yoshii Gallery, New YorkAraki typically depicts his subjects, mainly women, in suggestive poses, and more often than not, tied up, and suspended in the air by ropes. In a post-Harvey Weinstein world where issues of sexual abuse and consent are so central to the #MeToo movement and conversation, Araki’s photos and the retrospective exhibit can certainly be seen as teetering on the line that separates art and exploitation. As HuffPost reported, Araki has himself been accused of improper behavior, although his accuser did not pursue the matter with the authorities, fearing professional repercussions.

Nobuyoshi Araki,1985 B & W Print

Courtesy of Yoshii Gallery, New YorkThe photo at the beginning of the exhibit comes from Araki’s 1997 photobook, Tokyo Comedy, a series of explicit and contentious images that helped cement his career. The photos in this series are known for “the collision of playfulness” (which can be seen with the flower and dinosaur), and makes heavy use of kinbaku-bi, a Japanese style of bondage that literally translates to “the beauty of tight binding.”

“The conversation in the West becomes not necessarily if this art is pornography or not, but rather if it’s sexist,” Mustard explained. “There’s a sort of language of bondage in the photos that depicts a heterosexual power dynamic.”

Araki’s kinbaku-bi photographs have been the center of controversy for most of his career. The bondage photos that show a woman helplessly hanging upside-down while she is sexually exposed have been often criticized as being offensive and demeaning.

Nobuyoshi Araki, 2007 C-print

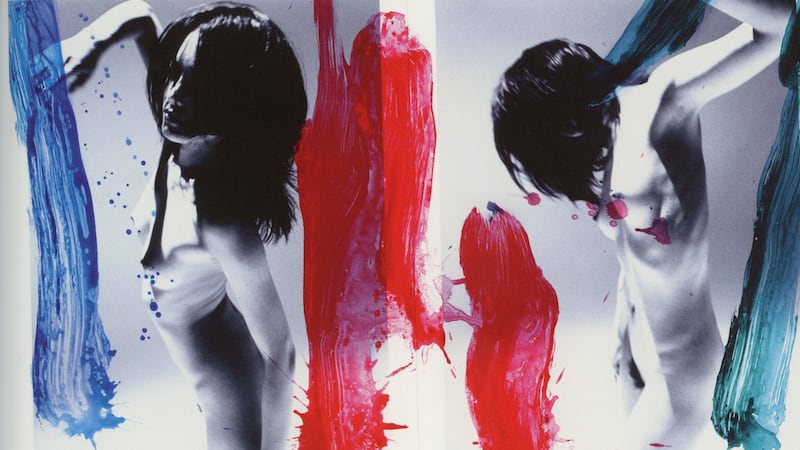

Courtesy of Yoshii Gallery, New YorkAs Araki’s popularity begins to grow in the ’90s, especially in the West, art critics begin to theorize that his work was gaining traction because the women in the photos were not white.

In 1999 art historian and curator, Christian Kravagna, discussed that Araki’s bondage photos were tolerated in the West due to “unresolved racism towards the imagery of East Asian women.”

“Araki’s kinbaku-bi photography is particularly popular in the West precisely because it exploits outdated and racist Eurocentric notions about East Asian women: ‘obedient and erotic at the same time,’” a portion of text at the exhibit reads.

Nobuyoshi Araki, 2007 Acrylic paint on 2 B & W prints

Courtesy of Yoshii Gallery, New YorkDuring an interview with South China Morning Post in 2017, Araki discussed the kinbaku-bi photos in depth, explaining that the models (including Lady Gaga in 2011) had consented to being tied up and suspended. The artistic value in tying up the models revolves around the idea of the heart being untethered to the physical world, he said.

“Kinbaku is different from bondage,” Araki explained. “I only tie up a woman’s body because I know I cannot tie up her heart. Only her body can be tied up. Tying up a woman becomes an embrace.”

Nobuyoshi Araki, 2007 Acrylic paint on 2 B & W prints

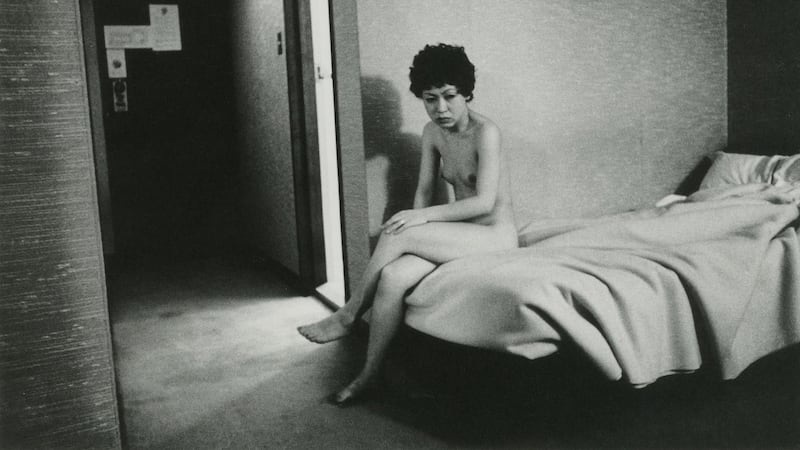

Courtesy of Yoshii Gallery, New YorkWhile his sexually explicit photographs is the most discussed part of Araki’s work, other photobooks in the exhibit display a wide variety of photos that depict a different side of Araki. For example, the photobooks Sentimental Journey and Winter Journey focus on Araki’s wife, Yōko, and entirety of their relationship.

The photo series begins with their honeymoon and ends with Yōko’s death from ovarian cancer in 1990. Photos include pictures of Yōko sitting on a train, and an intimate photo of her curled up in a boat in fetal position on the Sanzu River in Japan.

Nobuyoshi Araki, 1971/2017 Gelatin Silver Print

Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo“She was exhausted from all the sex,” Araki had said during interview according to a small bit of text next to the image. “I had no intention of taking a picture like that so I feel like maybe God or someone made me take that picture.”

The photos in this set definitely show a quieter side of Araki. While nudity is still present, the photos of his wife sitting naked at the edge of the bed after having sex, evoke a sense of tenderness, rather than shock. Araki also manages to capture the loss of this affinity when he takes a photo of his wife in her casket during her funeral in the second part of the book, Winter Journey, which followed Yōko’s struggle with ovarian cancer.

Nobuyoshi Araki, 1989-90/2005 Gelatin Silver Print

Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo“It’s such an evocative photo,” Mustard said. “Sentimental Journey and Winter Journey are really great examples of the idea of the mundane. The simplest of photos are so infused with emotion. There’s this sort of shamelessness in how open he is to making moments that should be intimate and private available to the rest of the world.”

Other photographs capture Tokyo nightlife. During the ’80s and ’90s, Araki spent time taking photos in the city’s red light district.

Nobuyoshi Arak, 1971/2012 Gelatin Silver Print

Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, TokyoThe photos during this period include images of Yakuza (Japanese mobsters) men having sex with prostitutes, and other sexual situations at karaoke bars and clubs. Fearing that his photos of seedy bars and prostitution rings would ruin Japan’s image, Araki was repeatedly arrested and fined by Japanese law enforcers.

“Araki documented this oppositional side of Tokyo as a reality,” Mustard explained. “It wasn’t just about the ‘obscenity’ of his work, but it was more about him showing this part of Tokyo that people would prefer not to be shared.”

Nobuyoshi Araki, 1971/2012 Gelatin Silver Print

Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, TokyoMustard hopes that topics that Araki explores in his work will spark discussions among Museum of Sex visitors.

“We want to be really upfront about the way his work has been debated and criticized,” Mustard said. “We hope that visitors have these kinds of conversations in the gallery, and afterwards.”

The exhibit runs until Aug. 31. More details here.