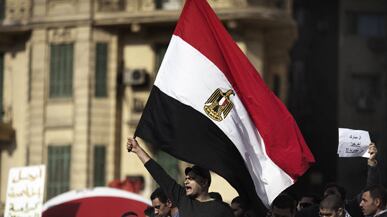

Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak has appointed a new vice president and prime minister but the cabinet reshuffle has done little to quell revolt on the streets. Plus, full coverage of the Egypt uprising.

The standoff between Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and the hundreds of thousands of his countrymen who say they are tired of his 30-year-long rule continued Sunday. The speed and scope of the upheaval in Egypt—the largest country in the Middle East, and one of the U.S.’ strategic partners in the region—has stunned the world.

Army helicopters and fighter jets swooped over tens of thousands of protesters gathered in the city’s central square late Sunday afternoon. Nobel laureate Mohamed ElBaradei—who has been chosen as the leader of an opposition coalition here—joined the protesters and told them there was no turning back.

Photos: Egypt Protests

On Saturday, Mubarak announced the appointment of intelligence chief Omar Suleiman as his vice president (a position Mubarak has never filled before) and former air force chief of staff Ahmed Shafik as prime minister. But protests—whose main demand remains that Mubarak step down—continued. “Mubarak, wake up!” protesters chanted Sunday. “It’s your last day!”

Meanwhile, as the country passed through this moment of exceptional instability, foreign tourists were trying frantically to leave the country, and the American Embassy is considering evacuating some of its personnel.

“I’ve been here four days. I won’t go home until Mubarak leaves or I die.”

Osama Ahmed, 40, stood in an intersection in the upscale neighbourhood of Zamalek, where he owns a shop. He and three other men from the neighbourhood waved cars through. “The police isn’t there,” Ahmed said. “We’re the alternative, till the situation stabilizes.”

Nagwa, a 24-year-old human-rights activist, who has been attending the protests, said there was looting of shops and ATMs in her neighbourhood Saturday night.

“We think the ministry of interior is doing this just to intimidate and terrorize the people,” she said. “So many people caught… turned out to be police or police informants. The fact that absolutely in every neighbourhood in Egypt this is happening, shows that it’s somehow organized.” Her friend Magda, 29 added: “It’s as if the ministry is sending the message to the people: See what you can do without us. We will step back from your lives and you will have no one to protect you.”

Ahmad Ibrahim, 27, a resident of the central Mounira neighborhood in Cairo, said men who showed state security IDs came through the roadblock he was manning early this morning. Further down the street, Ibrahim and others saw a minivan dump the dead body of a man who had been shot.

With the police absent and the security forces inspiring greater fear and distrust than ever, many here are looking to the Egyptian army, which is currently protecting major buildings but not clashing with protesters. On the contrary, army tanks are covered with anti-Mubarak graffiti and citizens regularly approach soldiers to offer them snacks or shake their hand.

Some military men have even joined the protests. Captain Ehab Fathi did so yesterday, wearing his army uniform. “I didn’t come as a member of the army,” he said. “I came as an Egyptian citizen who is suffering and expressing his views.”

The protestors’ demands, said Fathi, are “the removal of Mubarak’s regime, starting with him and all the way down. The organization of a transitional government that will write a new constitution; the holding of clean elections in which we’ll chose someone to lead us for the next period—for a fixed period, like any advanced country. No one will govern us for his whole life.”

But the intentions of the higher-ups in the Egyptian military—all of whom are implicated in Mubarak’s regime, and benefit from the large privileges and commercial interests the army has here—remain unclear.

In Tahrir Square on Sunday, Ayman Ragab had nearly lost his voice from chanting but was still eager to talk to a foreign journalist. The young man said when he heard of the first protest last Tuesday; he took a train from southern Egypt. “I travelled 450 kilometres,” about 280 miles. “I’ve been here four days. I won’t go home until Mubarak leaves or I die.”

Ursula Lindsey is a Cairo-based reporter and writer.