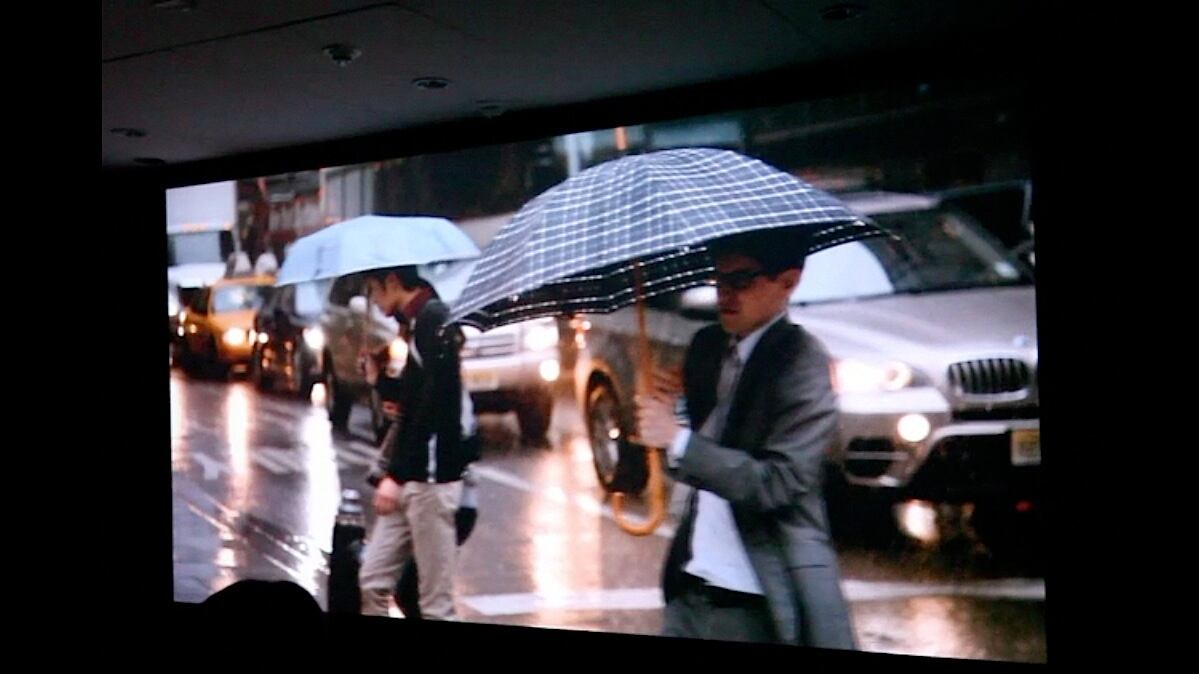

It’s video week at the DP, and this is a still from “Street”, an utterly engrossing projection by James Nares that’s now drawing crowds at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. (Click on the image to view a clip that was shot in situ, or go to Nares’s Web site for a different one.) “Street” is nothing more than one hour’s worth of footage culled from 16 hours spent riding a car through the streets of Manhattan, with a video camera pointed out at the pedestrian flow.

What seems to account for the video’s almost magic, irresistible attraction is that it is shot in extreme slow motion and at very high definition. Nares has taken the slow-mo technology usually used to capture the flight of a hummingbird and trained it on his own species, as it too goes about its normal business.

Today’s very extended Daily Pic looks at how that tech causes the video’s entrancing effects, and it includes some guesses from a couple of experts: Alvy Ray Smith, the computer scientist who co-founded Pixar (and who happens to be my brother-in-law) and the Berkeley psychologist Arthur Shimamura. Click “Read Full Story” below to see our dissection of the video’s effects.

– A Slow Trip Through A World Slowed Down: Although it’s clear that the figures that we see on the sidewalks have been artificially slowed – it takes 12 seconds for an umbrella to pop open – we don’t feel as though the progress of Nares’s car has been equally decelerated. Even though that car must have been traveling the streets at a fair clip, to keep up with other traffic, we feel that it is (and we viewers are) moving at a real and normal snail’s pace. In other words, we feel that we are moving at a slow, stately rate through a universe whose contents have been abnormally slowed. At a guess, that could be because we identify completely with the lens of the camera, so that anything it sees feels like it has been seen with our own, untroubled, unmanipulated vision. The effect may also depend on the fact that there aren’t many cues in the scene to tell us how fast our car is really going (a car going 5 and a car going 30 witness basically the same streetscape, though passing by at different rates) whereas the pedestrians’ gait and actions – such as unfurling that umbrella – have a standard duration that we recognize as having been lengthened in Nares’s video. Slow motion filming almost always involves a static camera pointed at a moving subject, which may be why Nares’s use of a moving slow-mo camera seems to produce such novel effects.

– A World Of Statues: Another odd effect of “Street” – and a central part of its fascination – involves the strangely artificial, crystalline quality that its figures take on, as though they have been carved from plastic rather than made of living flesh. (This is really only visible in the full-scale projection at the Met; the effect reminds me of how people describe the world they see – or feel – while tripping on LSD.) The pedestrians register as more like Duane Hanson’s utlra-realistic Pop Art statues, with added animatronics, than like real human beings captured on film. I thought at first that this might be because of the lack of “motion blur” in Nares’s footage: slow-motion cinema requires a very high shutter speed for each frame, so that the blur you get in each frame of a normal video or film (and which is necessary for the projected motion to look smooth) is lacking in “Street”. Shimamura agrees that this could be central (see his blog posting about the issue) but Smith isn’t so sure: He was one of the people who first learned to add motion-blur to digital animation, to take the jitters out of its figures’ movements, but he says he doesn’t remember any excess, artificial-looking sharpness being an issue. On the other hand, he notes that there isn’t any motion blur in natural vision: “When we fix on a moving object and track it, it has perfect edges; We’ve essentially stopped it”. So it could be that our ability to see crisp edges in a moving object in “Street” reads to us as un-cinematic, and therefore trippy and artificially hyperreal. Then again, it’s not as though sharpness normally makes figures look artificial, say in a still photo – quite the opposite, sharper figures in still photos look more real and natural, not less so. Maybe the hyperreal effect in “Street” has something to do with the slow-mo: Only some kind of machine could move as slowly as these figures do, so we read them as mechanical and therefore “feel” them to be artificial. Or maybe slow-mo always seems too “crisp”, because it lets us recognize features (moving cloth, flying hair) that would normally go by literally “in a blur” in real vision. So we assimilate those un-blurred features to the realistic sculptures where they have been made available in the past – or simply to real static figures where those features could be inspected. That is, we imagine Nares’s figures to be static (“carved”) rather than real, because only if they were static could we read their features so clearly. Whatever the cause, the artificial feel of Nares’s figures – their clear sense of being the product of illusionistic craft – gives them the fascination that trompe-l’oeil always has. Weirdly, if we could fully lose ourselves in the scene, the way we normally do with movies, what we see would seem so transparently real that it wouldn’t be recognized as “real-istic”. That is, because Nares’s figures don’t read as fully real – because they read as somehow artificial – they impress us with their striking real-ism, and keep us glued to his piece!

– Rounded Cutouts: Here’s what’s even weirder: The figures in “Street” look excessively crisp and sculptural, but they also, and paradoxically, register as looking like cutouts. It’s almost as though their edges are so sharp, we think of them as having been cut and embossed in full relief from tin – as though we don’t imagine that they have equally rounded rear sides. Each cutout figure could almost be sliding along in a little track of its own, without much distance between it and the smaller figures behind, also moving on their own little tracks. (This, in fact, was how depth could be enhanced in some cel-based animation, thanks to “multiplane” cameras.) Alvy Ray Smith wonders if that couldn’t in part be because of the extra time we have to observe these moving figures – we expect them to pass quickly into the blurring of peripheral vision, and since they don’t, we can only think that they must be flat photographs. That is, the only time that we normally get to witness a moving figure that also remains crisp wherever it is in our field of vision is when that figure has been slowed right to zero in a still, flat photograph – so we attribute the same flatness to each of the “cut-out” figures in Nares’s video, as they proceed in independent motion through his cityscape.

Another contributing factor might be the shallow depth of field in Nares’s video, necessitated by his fast shutter speed. Foreground figures in “Street” are wildly out of focus, which is normally a feature that we only see in still photographs. (Depth of field is essentially irrelevant in human vision, because we refocus our eyes on anything that we’re attending to; it takes great effort to “see” the blurring of objects in front of or behind the one we have focused on.) Filmmakers rarely keep an out-of-focus figure on the screen for long, so when we see one lingering in our vision in “Street”, it reminds us of similar figures seen in still photos – and the photographic flatness perceived in those figures then has a contagious effect of “photofacticity” across Nares’s entire scene, leading to that cutout feeling. (Actually, I don’t think any of these explanations of Nares’s “flatness effect” are quite right. I’m hoping that some psychophysicist weighs in with a better one.)

– One final thought, and worry: I must have spent well over an hour with the piece, and enjoyed it as much as the rest of the crowd. But I wonder if any piece whose pleasures seem so much built around its technical effects, rather than its content, risks losing steam and appeal over time. If I imagine the same view of New York seen without the HD slow-mo, I can’t quite believe it would mean as much. Nares’s technique reminds me of the first pictures to use systematic perspective in the Italian Renaissance, and how technophilic they seem. Come to think of it, that would make Nares our modern Uccello, about which I can hardly complain.