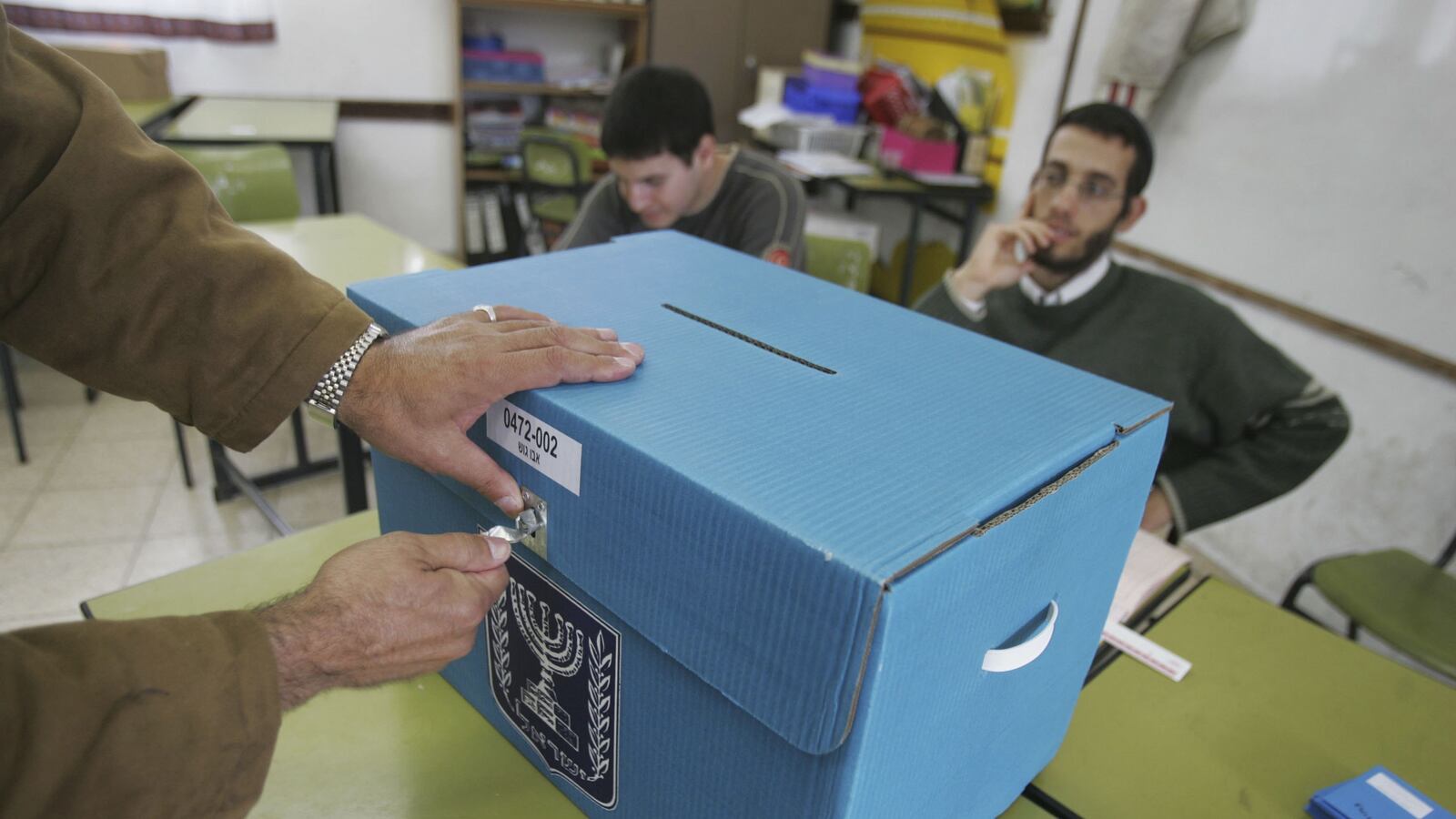

A fight is brewing within the Israeli government coalition, between those who want to hold a referendum on any final peace deal with the Palestinians (Naftali Bennett, Benjamin Netanyahu) and those who don’t (Tzipi Livni, Yesh Atid, and Avigdor Lieberman). The idea is to have the Israeli public vote on whether giving up land under Israeli control is acceptable or not.

Most would probably say that talking about a referendum now is getting way ahead of ourselves; there isn’t even a real peace process at this point in time. Even still, it’s important to think broadly and long term, particularly about the way that the Israeli and Palestinian governments can bring their peoples along with them in any final resolution. But a referendum is not the right policy to do that.

In point of fact there is currently a law on the books that requires a referendum on withdrawal from areas subject to Israel law—which includes all of Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, but not the West Bank. At the moment the idea seems to be to require a referendum on giving up lands under Israeli “sovereignty,” which means any land swaps (territory in Israel for settlements) that are part of a final agreement would need public approval. Naftali Bennett's Jewish Home party wants to make this law a Basic Law, and there’s some uncertainty whether the party would want to extend the jurisdiction of the law (i.e., to all of the West Bank).

In effect, though, including land swaps in the law would tie a final peace treaty to a public referendum, since any agreement will almost certainly include land swaps. Both official negotiations and track-two diplomacy between Israelis and Palestinians have by now entrenched the idea that at least some settlements will be annexed to Israel, in return for some Israeli territory being annexed to the Palestinian state.

There are some plausible arguments for a referendum. It would provide any final agreement with the support of a majority of the population, which is useful for the success of such a treaty; it could provide a sense of national unity at a moment of dramatic change; and it would provide cover for those who oppose land withdrawals, allowing them to accept the “will of the people,” while undermining the ability of spoilers by demonstrating broad support for the agreement.

But the counter-arguments are even stronger. In democracies, populations elect leaders to make decisions on national security (among other things). It is not more democratic to run back to the public for approval of specific government policies. If segments of the population oppose a decision, they have the right to protest against it in a variety of (legal and legitimate) ways, including threats of removal from office at the next election. Israeli leaders will certainly be aware of the importance of a decision on a final peace treaty, and if they decide it is important enough to go ahead with even in the face of opposition, that is simply what leaders do.

In addition, there are many other ways that governments can speak to their populations. And in this case, there is already plenty of polling data that a majority of Israelis support leaving most of the West Bank. A referendum seems to be redundant.

At the same time, there was no referendum on the 1947 Partition Plan, the decision to accept the 1949 armistice lines, the 1979 treaty with Egypt, 1981’s annexation of east Jerusalem and the Golan, the Oslo Accords in 1993, the agreement with Jordan in 1994, the 2000 withdrawal from Lebanon, or the Gaza withdrawal in summer 2005. In short, on none of the big issues of peace and security—all of which directly impacted on the personal safety of individuals as well as the security of the state itself—was the public asked to decide.

There is also the question of legitimacy. Approximately 20 percent or so of Israel’s population is Arab, and it’s not clear how this would be incorporated into any law on referenda. Of course no distinctions between citizens should be made at all, but one can imagine a scenario in which large numbers of the Arab community vote for a peace treaty and carry the percentage of supporters into the majority. Would the referendum be dismissed by rightwing parties because it wasn’t “Jewish” enough? Would those pushing for such a law—namely, the religious Zionists and secular nationalists—try to incorporate stipulations about how many of which group must vote for the referendum to count? This would undermine the whole point about referenda being “democratic,” and, worse, undermine the communal and individual rights of both Jews and Arabs and Israeli democracy as a whole.

Perhaps most importantly, given that developments in security and foreign affairs are often fluid and context-dependent, tying the hands of future governments on such critical issues is short-sighted, foolhardy, and counter-productive.

In short, the very discussion of such a referendum represents an effort to impose specific ideological ideas on the entire country and ties the hands of government. Indeed, the existing law on referenda should be scrapped entirely.