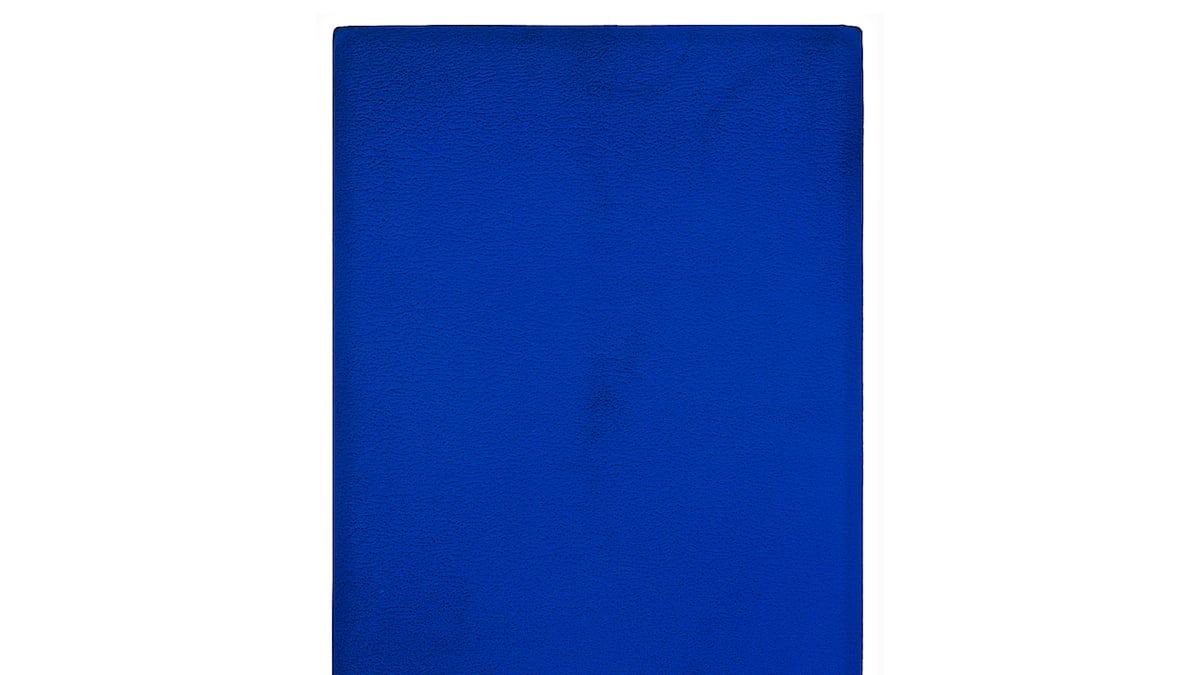

This untitled blue monochrome, painted by Yves Klein in 1956, is just a stand-in for another, unreproducible Klein that I had the luck to experience last night in New York. Dominique Levy’s new gallery, where the monochrome is now on view in her inaugural show, also organized the first American presentation of Klein’s “Monotone-Silence Symphony”, in which a full orchestra, with chorus, hold a single chord for 20 long minutes then rests for another 20, during which the audience is also expected to maintain silence.

I had thought the work would be a clever piece of absurdist conceptualism, as I’ve insisted that many Kleins really are. Instead, it turned out to be richly perceptual and affective.

The 20-minute single chord leads you to notice every minute variation in its sound: One bass-player’s bowing; one soprano’s warble; the pulse of the orchestra’s thrum. It seems you can be far more immersed in a single sound, and more attentive to it, than you can ever be in a sight. It’s very unlikely that you’ll ever attend to a monochrome painting for the twenty minutes that you attend to Klein’s monotone; as is often said, and as Klein proves, you can turn your eyes from a sight as you can’t turn your ears from a sound.

In fact, Klein’s sound attracts your eyes as much as your ears. Looking intently at the endlessly open mouths of Klein’s choristers, I couldn’t help comparing them to the mouths of the chorus of angels in a Renaissance altarpiece, open for all eternity. And the aural evocations are similar: Klein’s piece calls to mind the crashing opening chords and fanfares of Monteverdi’s celebratory vespers of 1610, but with the celebration dragged out for the length of his piece.

Klein’s silence proves just as eventful, and even harder to ignore. As you attend to the musicians’ non-playing, every tiny break in the silence – each creak of a chair or honk of a distant horn, or even the sound of your own gut – attains a presence it would not normally have. As a rest in an orchestral score, no different in essence from a rest that might last the length of a note or a bar, Klein’s silence achieves a state of indefinite yet specified duration that’s almost magical. The instant when it ends, and the conductor lowers his arms, becomes more fraught than it has any right to be. (In this, that closing moment reminds me of how the ultra-slowed motion of Douglas Gordon’s “24 Hour Psycho” contrasts to the unslowable instant of each cut in that film.) I can honestly say that I could have used another 20 minutes each of sound and silence.

A piece that I expected to be done the moment I’d absorbed its conceptual premise still resonates with me now, as I write.

For a full visual survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.