When the news broke this week that National Security Staff official Jofi Joseph had been fired for his acerbic, anonymous tweets as @natsecwonk, it was heralded as a new low in the annals of diplomatic privacy. It was just the latest confirmation, the thinking went, that the secretive world of international statecraft has been forever turned upside down—a small-but-telling postscript in the Age of Snowden.

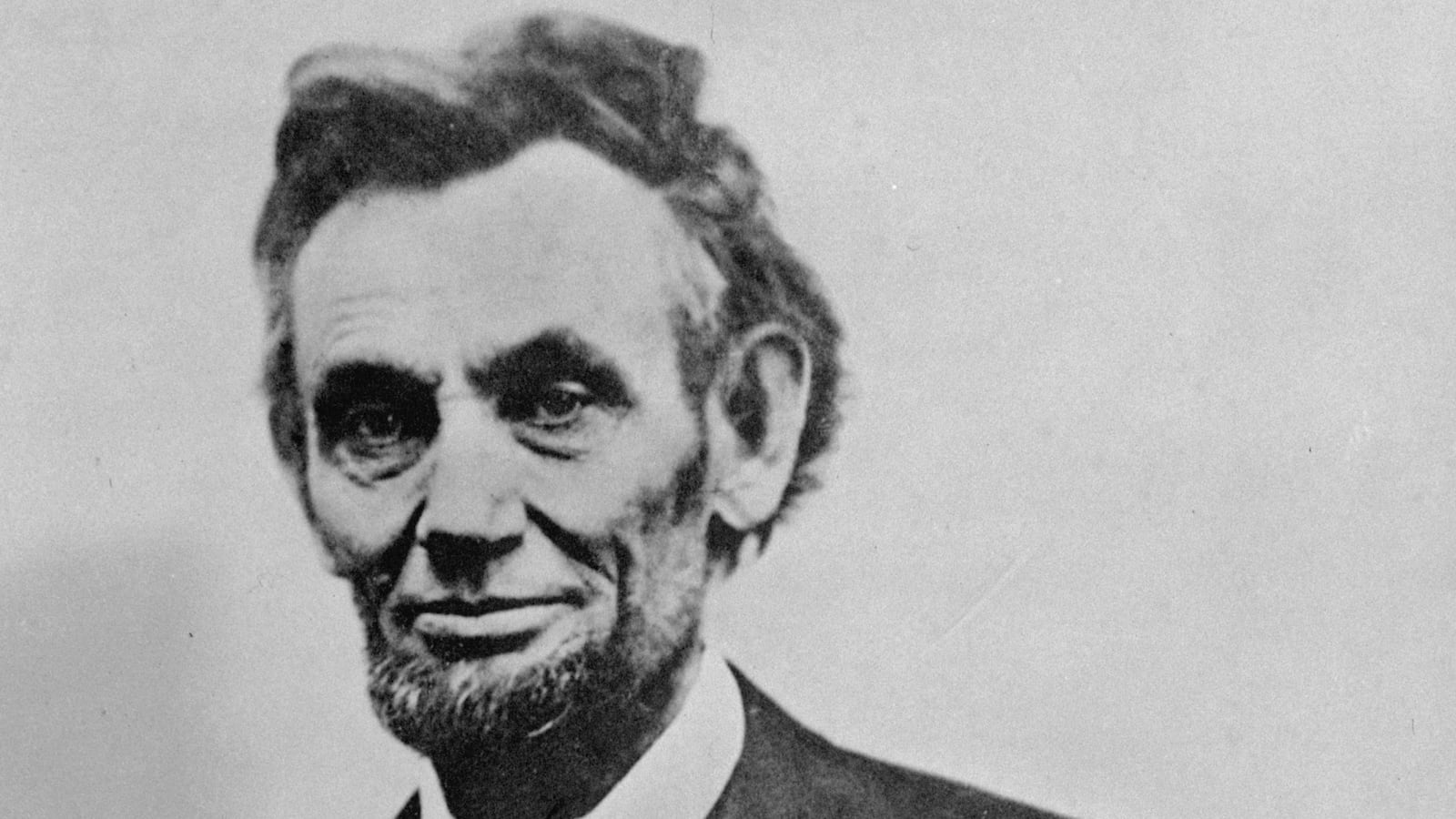

It is worth remembering, however, that diplomats in all eras have struggled with the question of privacy. Even Abraham Lincoln—preoccupied with the Civil War at home and not often remembered for his role in international affairs—had to flush out a mole in his State Department. In 1862 Adam Gurowski, an abrasive Polish count who was working as a translator at State, was fired after he published his tell-all diary. Gurowski, an eccentric and colorful character who liked to greet visitors in the nude, took pointed swipes at all kinds of top Lincoln Administration officials in his journal and letters—including the president, whom he referred to as “pighead Lincoln.” Gurowski labeled Secretary of State William Henry Seward (his boss) an “ass,” and described his job as trying to “keep Seward from making a fool of himself.”

Gurowski’s story is fun, but it is more than just a novelty. Lincoln’s America, like our own, was filled with an increasingly dizzying array of news sources. The telegraph and steamships, meanwhile, were dramatically shrinking distances. Lincoln, like President Obama, struggled with the question of how to conduct sensitive diplomacy on a globe in which nothing was private. (“Diplomacy has so few secrets nowadays,” observed one of Lincoln’s contemporaries, the French Empress Eugénie.) Taking a closer look at the tale of Lincoln’s “Twitter mole” yields some important lessons for diplomacy in our own times.

A European nobleman with strong antislavery views, Gurowski had immigrated to the United States in the years before the Civil War, working as an author and journalist. His job allowed him to develop powerful connections in the U.S. capital; Gurowski, like Joseph, was an insider. “He did not need to use a keyhole for collecting information,” writes Gurowski’s biographer, LeRoy Fischer, “because he knew everyone of political and military significance in wartime Washington. He simply walked in, sat at other men’s desks, openly rummaged through their papers, and at other times extended unsolicited advice or impetuously broke into statesmen’s conferences.”

Like Joseph, Gurowski displayed a relentless superiority complex, eviscerating pretty much everyone in the Federal government. (And their wives—he likes to refer to Mary Lincoln as “that Springfield bitch.”) The president, he wrote, possessed “a rather slow intellect.” The count considered Lincoln an “honest man of nature, perhaps an empiric, doctoring with innocent juices from herbs.” Still, he believed, the men around the president were “quacks of the first order.” It is worth noting, too, that for all Gurowski’s vitriol, he sometimes identified genuine weaknesses in Lincoln’s foreign policies. While the president persistently favored sending free black Americans to colonies in Africa or Central America, Gurowski rightly thought that policy absurd: “As stupid as it is recklessly cruel.” Nevertheless, when Gurowski publicly aired his grievances, Lincoln and Seward had no choice but to cashier him.

What, then, can we learn from Gurowski’s story? American statesmen for decades have been performing a kind of high-wire act—single-mindedly pursuing U.S. national interests while at the same time appealing to universal values. That approach, for all its flaws, has served the country well enough in the international arena. Now, some scholars are beginning to argue, the end of diplomatic secrecy is leading to the “end of hypocrisy”—an inability of American statesmen to square their narrow interests with common liberal values. In their brilliant short essay in the most recent issue of Foreign Affairs, titled “Foreign Policy in the Age of Leaks,” Henry Farrell and Martha Finnemore argue that U.S. leaders will increasingly need to make a choice: either unapologetically pursue their interests—a la Vladimir Putin—or make a genuine effort to act in accordance with American values.

Lincoln, however, proved that it was possible to do both, even in an information age. The sixteenth president was “the quintessentially American practical idealist,” as one modern diplomatic scholar puts it, skillfully pursuing both humanitarian values and the national interest as he saw it. Lincoln ended slavery—partly in an effort to appeal to European liberals—but he took his time in doing it, unwilling to upset the sectional balance or violate the law in the process.

Gadflies like Gurowski and Joseph who thrill in pointing out the inevitable hypocrisies of powerful men will always exist—and have their role in a democratic society. Still, 150 years later, it is Lincoln who is remembered as the president who saved the Union; the cynical Polish count has been all but forgotten.