Perhaps the only bothersome byproduct of the Great Golden Age of Television we're currently living in is the fact that all of us now feel compelled to evangelize—incessantly—on behalf of our most beloved shows. How many times has a friend or coworker insisted that You.Have.To.See [Insert Critically Acclaimed Series Here]? (No, seriously—you have to.) Try sidling up to a bar in Brooklyn and announcing that you've never seen a single second of The Wire or Friday Night Lights. Watch what happens next.

And so I'm well aware that when I say You.Have.To.See True Detective, the new hour-long HBO drama debuting this Sunday, January 12, your defenses will automatically go up, and that when I begin to elaborate—It's a crime show about two cops! One is an Average Joe! The other is an Intellectual Weirdo! Surprise! They're mismatched! But despite their differences they have to solve a satanic murder mystery together! In Louisiana, a land rich with swampy Gothic crime stories and compelling motion-picture tax incentives! Oh, and it stars Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson!—you will probably shut down completely. I get it. On paper, True Detective sounds like yet another celebrity-studded CBS crime procedural—CSI: Baton Rouge—or even worse, The New Series from the People Who Brought You Homefront.

But I don't care. I'm going to evangelize anyway. True Detective may very well be the best show of 2014. Yes, the year is only 11 days old. And yes, I've only seen the first four episodes (of eight). But I'm willing to bet that when I compile my Top Ten list next December, True Detective will still reign supreme. Judging by the initial installments, it's not only one of the most riveting and provocative series I've seen in the last few years; it's one of the most riveting and provocative series I've ever seen. Period. And despite—or perhaps because of—the somewhat cliched premise, it has the potential, in its own quiet way, to be one of the most revolutionary as well.

ADVERTISEMENT

Here's what you need to know about the plot. It's 1995. Martin Hart (Harrelson) and Rust Cohle (McConaughey) have been partners in Louisiana's Criminal Investigation Division for three months. Hart's the good ol' boy type: wife, kids, mistress, no-nonsense demeanor, the beginnings of a paunch. Cohle is different. Whip-smart, whippet-thin, and boyishly clean-cut, he's a haunted, misanthrophic former undercover narcotics detective from Texas who lives alone in an unfurnished room and takes so many notes on his oversized legal pad that colleagues begin to refer to him as "The Taxman." No one seems to notice that he resembles a young Harry Dean Stanton.

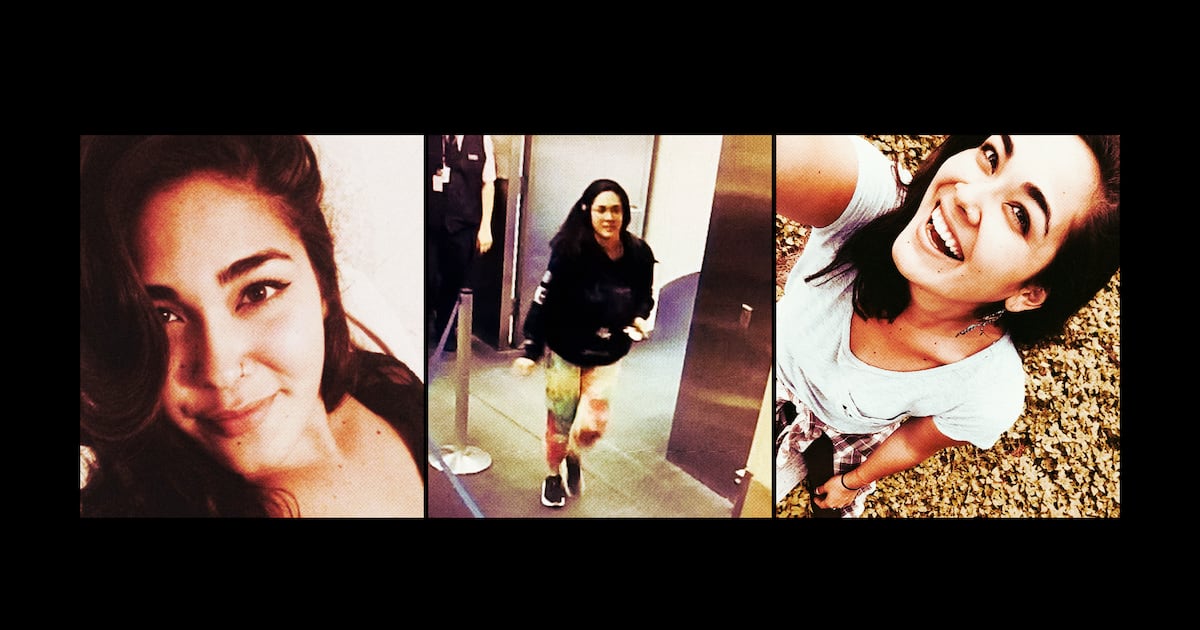

One day, Cohle and Hart catch a new case in rural Vermillion Parish: the murder of an underage prostitute named Dora Lange. Apparently she was dosed with crystal meth and LSD, stripped, raped, blindfolded, strangled, stabbed several times in the belly, adorned with a crown of twigs and a pair of deer antlers, and then bound and posed in a prayerful position at the base of a large oak tree hung with handmade "devil catchers." Cohle is certain that a serial killer did it. "Her body is a paraphilic love map," he mutters. Hart isn't so sure. "Once you attach an assumption to a piece of evidence," he retorts, "you start to bend the narrative to support it."

The Lange murder—who's the culprit? how do we nab him?—would be narrative enough for most shows. But True Detective isn't most shows. Only part of the story is set in 1995. The rest takes place 17 years later, as Cohle and Hart separately tell investigators (who've stumbled upon a new, uncannily similar killing) the story of how they cracked the Lange case and why their partnership ended. Hart, now besuited and bald, still works at CID; presumably he's been promoted. Meanwhile, Cohle—graying Deadhead ponytail, menacing Fu Manchu mustache—tends bar and spends his days off drinking "Milwaukee's Best or Lone Star. Nothing snooty." As the interviews unfold, we begin to catch little clues about what happened to Cohle and Hart after 1995—Hart is divorced; Cohle seems to have contributed—and True Detective methodically reveals its actual ambitions. The Lange murder is just a Trojan Horse. The real story here is much richer and stranger: who are these men, and how did this murder change their lives?

Capitalizing on the hackneyed conventions of the CSI genre to investigate character—as opposed to just another creepy murder—is a brilliantly subversive move, and it transforms True Detective into a much finer show than it would seem, at first, to have any right to be. But what makes the series potentially revolutionary, I think, is its format. Like American Horror Story, but unlike pretty much every other program on television these days, True Detective is designed to tell one story per season. When the eighth episode airs on HBO later this winter, the tale of Russ Cohle and Martin Hart will be over; Season Two will track different detectives on a different case. Even more unusual is the fact the all eight episodes were written by a single writer (Louisiana novelist Nic Pizzolatto, who also served as showrunner) and directed by a single director (Cary Fukunaga, who previously helmed 2011's atmospheric Jane Eyre adaptation).

This is a big deal. For more than a decade now, the best TV shows have been routinely surpassing their cinematic equivalents in terms of quality and impact. It's hard to name a movie character who made a stronger impression on viewers recently than Tony Soprano, or a big-screen plot that was more engrossing than Breaking Bad's.

But television still has some handicaps. Despite the rise of the all-powerful showrunner, it's largely unheard of for a lone auteur to exercise as much control over the look, tone, and language of a cable drama as say, Martin Scorsese (collaborating with screenwriter Terrence Winter) did over The Wolf of Wall Street; the vast majority of TV shows are still created by rotating crews of writers and directors. Meanwhile, every movie is finite (as interminable as Wolf might have felt): they all come equipped with both a beginning and an ending. But television is the opposite; theoretically, a series could go on forever. Even if a showrunner knows how he wants to wrap up his series from the second he sits down to write the pilot, he almost never knows how many seasons he'll have to fill with story before he gets there. And so even the greatest TV series tend to be bogged down by endless—and endlessly convoluted—second acts.

Which isn't always a bad thing: Anyone who wishes The Sopranos had conformed to a more linear storyline probably deserves to swim with the fishes. Even so, the True Detective model—one writer and one director telling a story with a beginning, middle, and end—is a valuable alternative, because not every narrative is best created by committee or best told as an open-ended epic. Imagine, for instance, if Homeland had adopted the auteurist-anthology template and killed Brody at the end of Season One—then moved on. It would be a vastly superior show at this point. For a certain kind of plot-centric series, the True Detective model could alleviate some of television's muddling structural issues and liberate showrunners to take full advantage of the medium's greatest asset: time. Some characters deserve eight hours on screen. In a theater, you can't do that. On TV, you can.

The problem, of course, is that some characters deserve more than eight hours on screen—including Martin Hart and Rust Cohle. It's going to be particularly painful to bid Cohle adieu at the end of True Detective's debut season. In part that's because of McConaughey's remarkable performance: a coiled, intelligent, perfect thing that should once and for all erase his hard-earned image as a shirtless stoner drawling his way through a perpetual string of interchangeable romantic comedies. It is some of the finest screen acting I've seen in a long time.

But I'll miss Cohle the character as well. For years, cable dramas have subjected us to antihero after antihero—bad guys, like Deadwood's Al Swearengen or Breaking Bad's Walter White, with whom we can't help but sympathize. At least so far, however, Cohle seems to be something else entirely: a heroic guy who's nonetheless deeply unsympathetic. (This is an agent of justice, after all, who refers to Earth as "a giant gutter in outer space" and considers "human consciousness" "a misstep in evolution.") Initially, we're meant to identify with Hart, who objects whenever Cohle's highfalutin Satre-isms get out of hand. "Stop saying weird shit like you 'smell the psychosphere,'" Hart snaps at one point. "It's unprofessional." But gradually Hart's more conventional ethics—he's a self-described Christian, just like "everyone else in a 1,000-mile radius"—start to fail him, and Cohle's antisocial moral code begins to emerge, improbably, as the more honorable approach. In the third episode, Hart and Cohle visit a tent revival in Cajun country. Cohle can't hide his disgust. “If the only thing keeping a person decent is the expectation of divine reward," Cohle says, "then brother, that person is a piece of shit and I’d like to get as many of them out in the open as possible.” True Detective is the rare show that's brave enough to make viewers so uncomfortable—and brave enough not to overstay its welcome once it has.