New arrivals to St. Kitts in the Caribbean can pay for a plot of land or even a passport to obtain citizenship, but not even long-term residents can buy their way into the island’s past. So when Maurice Widdowson, a boyish, Paul McCartney-type expat, wanted to know what was underneath his land on the island’s oldest plantation, Wingfield Estate, he began the laborious process of digging through time, unearthing layers of soil and debris hoping to expose overgrown physical structures, and maybe reveal some long-buried secrets.

Widdowson, a dapper businessman clad in the crisply pressed shirts and perfectly creased pants that hint at the past he walked away from as an executive in a fashionable London department store in the swinging ’60s, brought in strangers to do the heavy lifting. They’ve uncovered evidence suggesting the estate is one of the oldest, if not the oldest, rum distilleries in the Caribbean.

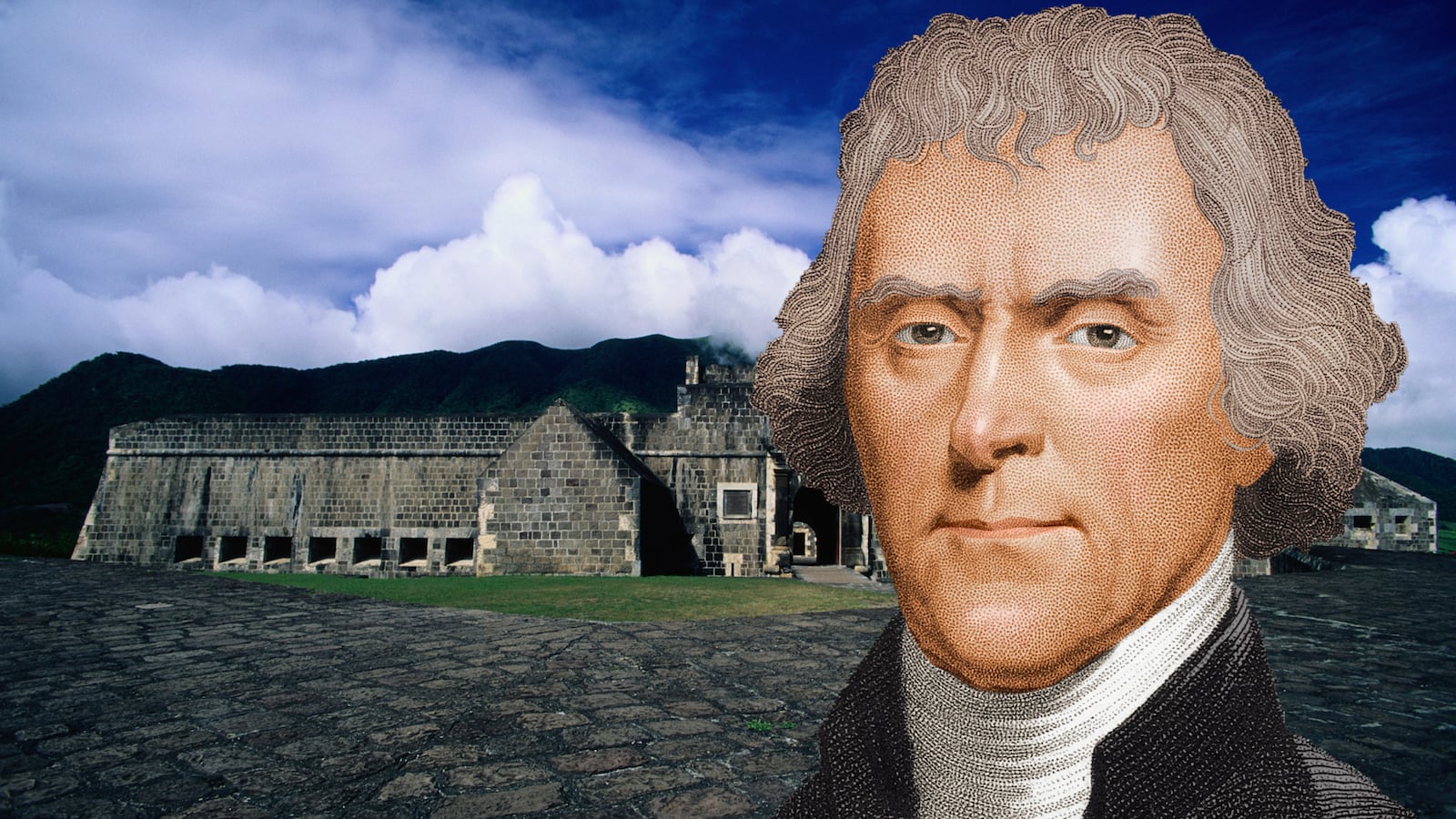

But there is other dirt here: this estate, the first plantation in the Caribbean, was once owned by the man islanders accept as an ancestor of Thomas Jefferson, and it was ground zero for the start of the region’s African slave trade. It was also the setting of a one-woman slave revolt that serves as a symbol of the anti-slavery movement on the island. That woman, an island hero, Betto Douglas, may have been a relative of the famous American abolitionist, Frederick Douglass. Like many things on the island, it’s still not clear.

While we’ve all heard about Thomas Jefferson being a slave owner himself, St. Kitts is where locals on the island say his ancestors learned the family trade. It’s accepted as fact in St. Kitts, but still not proven, that Jefferson’s forefathers, last name spelled Jeaffreson, boarded a ship called “Hopewell” in 1624, along with other émigrés, to start the first British colony in the Caribbean. These early British settlers soon established tobacco then sugar cane plantations and started importing workers to toil on them.

According to the Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, Samuel Jeaffreson—the one on the ship—had a son, Thomas, who was born in St. Kitts and eventually settled in Virginia, seemingly making him the same Thomas who was the president’s ancestor. Maybe. Record keeping was apparently not a priority then. “We just don’t know, I wish we did,” Anna Berkes a research librarian at Monticello says of the unproven lineage.

What we do know is this: No nation transported more African slaves to the Americas than Britain in a trade triangle that started in either London, Liverpool, or Bristol. Ships carried weapons and gunpowder to Africa, then loaded on human beings. From the Caribbean they brought island sugar and rum up to the colonies and sent it all back across the ocean to start the cycle again.

St. Kitts even played a role in the original white slavery—Irish nationals banished for political crimes and religious cleansing in the 17th century. Tens of thousands were sent here and to Barbados, Virginia, and New England following the ethnic cleansing of the Confederation War in the mid-1600s. The nearby island of Montserrat was nearly 70 percent Irish slaves at one time, earning it the nickname “The Emerald Isle of the Caribbean,” not only for its geographic resemblance to Ireland, but also because of the populace’s ancestry.

Reports at the time indicate Irish lives were cheap, literally: they cost one-tenth the price of Africans. They were burned alive and their heads put on stakes when they “misbehaved.”

There’s no evidence of the generations of misery slaves endured on site today. For the past 200 years, the Jeaffreson-owned Red House Plantation together with the Wingfield estate have been called Romney Manor (no relation to the presidential candidate). That’s where I joined a group of volunteers to look for answers in the soil about what may have happened here.

Unlike every other island in the region that abandoned sugar production generations ago, St. Kitts clung to it until recently. The last sugar factory shut down in 2005, and now the island is playing catch-up to embrace last century’s tourism boom, hastily paving roads and building up condos and hotels on beachfronts that have remained as early explorers first saw them, trying to rapidly shift its economy.

The train line that once trundled cane down the coast is now a scenic railway. A master-built community is crawling up the slopes of the rainy side of the island’s most famous volcano, and the region’s first Park Hyatt is anchoring a beach. A brand new private jet terminal sits across the road from the rusted skeleton of the defunct sugar works, suggesting an almost cargo cult if-we-build-it-they-will-come hopefulness.

While construction projects ring the island, citizens quietly wring their hands, upset about high-rises going up in places where low-slung buildings were promised, including one development encroaching on a mangrove wetlands area.

Islanders calling for sustainable tourism options may be too late. A popular beach bar was bulldozed to make way for a dolphin swim attraction. Hilltops are being sliced into parcels for massive condo projects. Opponents are reluctant to complain, “fearing repercussions.” On little islands, at close quarters, being outspoken draws attention. The secrets are big.

It’s easy to envision what might be coming next: traffic congestion and roadside pollution. Driving to Wingfield each morning feels like watching a movie with dread as we pass rural snapshots like nibbling goats and uniformed hand-holding elementary school kids carefully picking their way across tall grasses.

There is no grand entry to the estate, just an overgrown foundation sprouting green soursop and one cow that glances up lazily from the field. To the left is the path to the island’s zip line, to the right, a slowed-down scene from the past. Beyond the salt-and-pepper weathered stone ruins, in the shadow of the sky-piercing smokestack, we step out and into a symphony of cheeps, squeaks, chirps, and long trailing whistles that sounds like the button “tropical forest” on a sound machine.

A riot of leaves walls off a bend in the river, a curtain of vines cascades from impossibly tall mango trees. At ground level: comically huge, flat-leafed plants that look like they come from a prehistoric diorama.

Although the setting is bucolic, nothing’s tranquil—everything’s on the move. In the past, donkeys would haul mounds of cane, ovens would be crackling with stalks as kindling, pots would be stirred, molasses drained.

Today a red bird swoops across the river low to the ripples, men rake the sparse lawn, a woman sets up her cold drink stand—a table and a cooler—in the shade. As it has been for centuries, this is a place of industry.

Using simple archeological tools—wire brushes and trowels to hack at the dirt—we clear mounds of debris, trying to figure out what a series of tiered rectangles might have been. We want to define the wall boundaries, which are only partly uncovered.

There’s talk of an indigo dye works in this area. Could these have been dye baths? At the moment they look like dirt-caked kiddie pools, long-drained.

Previous excavations turned “what ifs” into “definitelys”—just two years ago, teams dug out an axle used in an 1800s waterwheel; the year before they excavated a grassy mound to reveal the ancient boiling house, where workers used copper kettles to concentrate cane juice.

I sweep aside clusters of leaves, clip vines, and brush away rubbery spiders. Wispy brown slender lizards slip out of my way. I scoop up styrofoam-white dots, before realizing, sickeningly, they’re clutches of eggs that look like beanbag chair beads.

Our group leader talks about wanting to “get rid of” an Angkor Wat tableau: trees growing right out of, and wrapping around the old stones. I consider them dreamy; he considers them large weeds.

As with the unproven Jefferson connection, uncertainty pervades. A piece of glass “may be” old, or “might be” something you can buy at a crafts store. Curved stones “might have” been for that waterwheel. No one says “No” or “You’re wrong.”

The current owner, Widdowson, remembers days lugging clothing samples in the old era of island travel, when he was stranded on Antigua so often by irregular flight schedules that he opened up shops there so he’d have something to do. Now he pours his fortune into the site, hoping to knit together a narrative that will exist once he’s gone. He knows it will be a work in progress forever, but hopes to add historical displays and a riverside memorial to honor the slaves.

In the nearly 40 years he’s owned it, Widdowson’s cleared a generation of brush and trees and created the island’s most well-known tourist attraction—Caribelle Batik shop— in the former residence up the hill. There, across a lawn from one of the oldest trees in the Caribbean—a broad saman—behind the cute cottages where tourists pluck bright blouses and eyeglass cases from display cases, workers dye colors onto fabric, adding more depth with each successive layer. In a way we’re doing the opposite down here, scraping away.

Start making a commotion in a small place and there’s usually someone attracted to the chatter or clank of tools, who might show up to lend a hand, or maybe a memory. On the last day that someone was Kelvin.

His shirt was torn, one of his worn sneakers was more like a rubber-soled barge—the SS Nike. He grabbed a shovel and started identifying mysterious birdcalls, naming previously unknown plants and trees. “They used to make earrings from these,” he said about the sandbox seed pods I’d been wondering about all week; he pressed two into my hand like a bribe, urging me to do the same.

“I don’t have a white shirt or a university degree,” Kelvin said when we discussed island preservation, “so no one will listen to me.” But he had what education and all the money the millionaire on the hill, or hopeful citizenship seekers couldn’t buy: “institutional” knowledge of the great outdoors and this setting.

Those giant prehistoric leaves? Kelvin remembered wrapping mackerel in them and eating them wild with seasoning. “Four o’clock tree, almond, manjack—we used that one to make our cricket bats; that was for cleaning,” he said, rapid-fire rattling off names. That bird whistle and trill? Both thrashers, the iPods of avians, able to store more than 3,000 tunes.

I asked Kelvin what else he remembered about this place and the rectangles. As kids, Kelvin said, they’d swim in these pools and the river, now a trickle, once flowed thick enough and high enough that, “We used to swing on these vines like Tarzan and Jane,” he said, grabbing one of the ubiquitous lianas, the same ones our group leader also wanted to clear away.

He remembered a footbridge the other volunteers had guessed at. They quickly tramped to the other bank to investigate while he recalled the crayfish in the pools just up the road in the Central Forest Reserve National Park.

Suddenly, seeing the pools and the crayfish seemed more important than chasing away spiders. Accompanied by an expat I took off on the forest trails.

Within minutes, we were picking our way across buttressed tree roots and hopscotching across rivulets in the stream.

I looked down into the pools and saw the crayfish, smelled overripe wild fruits, heard famous green vervet monkeys crashing through the leaves, and marveled at an avocado grove that appeared untouched for years.

Back at the site, the workweek done, I left Kelvin my gloves, he left me with a sense of what’s important on an island: getting to the bottom of things not just by digging, but by listening to a stranger reminisce. The island might be quickly changing, but the past remains alive among those who can still describe the days when being connected meant to nature, not Wifi, and a rectangle full of water was an excuse to play; when, instead of guarding their stories, islanders released them freely, to anyone who cared to ask.