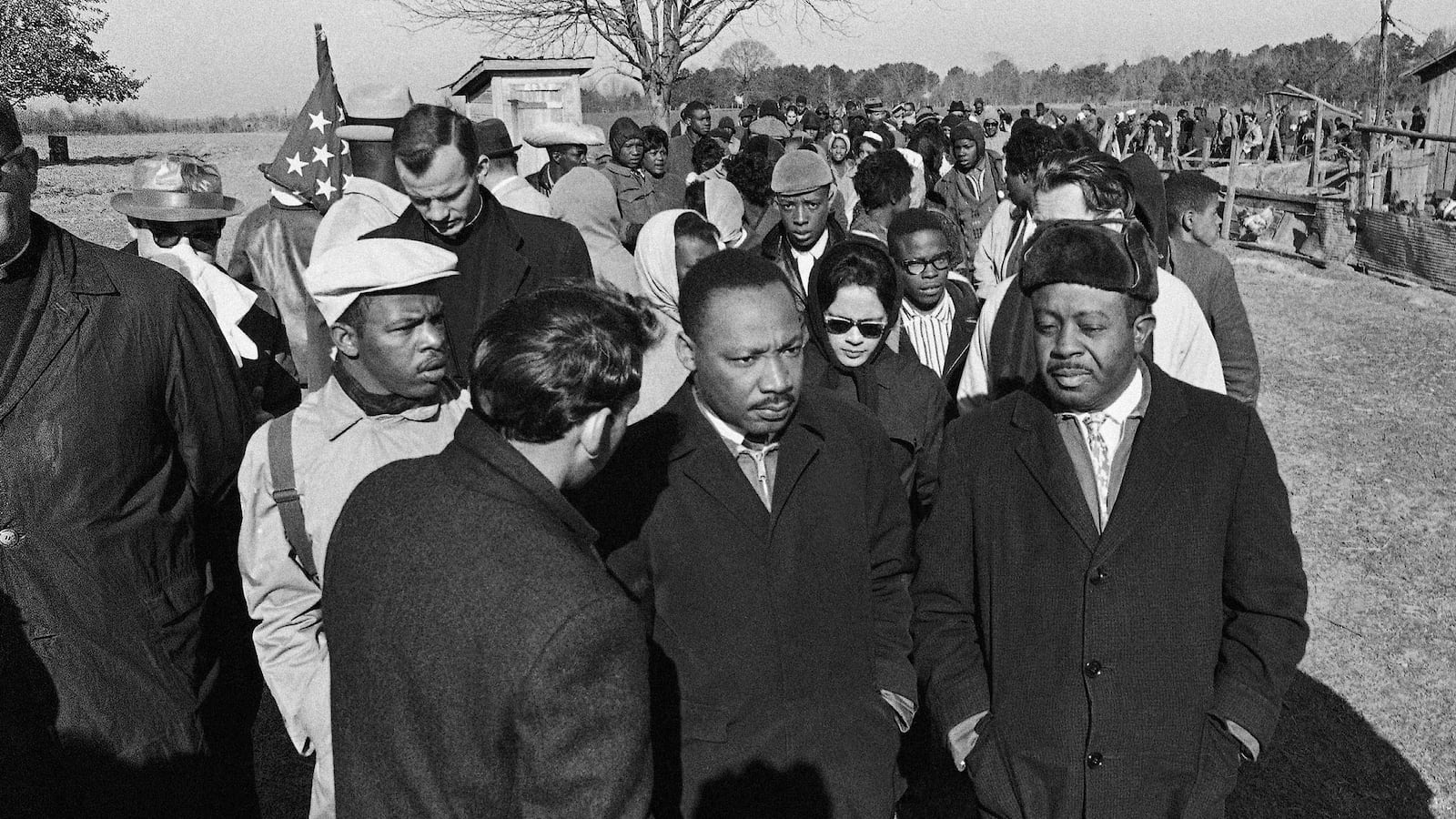

Ernie Washington was nearly 18 on that day 50 years ago when Sheriff Bill Clark and his all-white crew of cops tried to prevent a wave of history from crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Tear gas, clubs and dogs slowed progress down on that Sunday. But the voices demanding equality were a lot louder and lingered longer and more powerfully than the screams, the horror and the brutal images Clark and his men carved into the ugly, barren landscape of race and hate in America.

“I remember seeing it on the TV news,” Ernie Washington was saying. “I remember my mom and my pop telling me to watch it. Watch it and remember it, they told me. Remember it.”

Spring turned to summer and Ernie Washington graduated from Boston Trade High School in 1965. Diploma in hand, he and his best friend “Sonny” Davis eagerly and proudly joined the United States Marine Corps, two young black men both thinking they were embarking on a great adventure. They hoped to see the world beyond the block where they lived.

“Only thing Sonny and I ever traveled on before was the trolley,” Ernie Washington was saying. “Now we were taking trains and buses and going to Parris Island for basic. It was exciting to us.”

A page fell off the calendar and ’65 became 1966. America was slowly sinking into a war in a far-off country neither young man had ever heard of before. The other war—the constant one against bigotry, prejudice and a hate so deep that its scars were being written in history—continued here daily, with hard-fought victories called the Voting Rights Act that slowly but surely took territory once held by segregationists.

“We were kind of naïve,” Washington remembers. “Sonny and I. Young and naïve. And proud too. Wore that uniform everywhere. We were Marines.”

On the streets where they had grown up together, in many of the cities of the land they called home, the sights and sounds of people holding hands, marching and singing “We Shall Overcome” had little impact on these two young men content to be part of a community with a proud history of its own. They were brothers among brothers, the few and the proud, ready to roll wherever they were told.

Another year fell into the dust and suddenly it was 1967. The force and voice and commitment to a cause found Martin Luther King pulling America closer toward a light in the distance called justice.

Then another voice called “Command” ordered Ernie Washington and Sonny Davis to saddle up and ship out to that place both of them were hearing about more and more each day of their service. Soon, two young men who lived less than two miles from a harbor in Boston that opened into the Atlantic Ocean, a body of water neither had ever set foot in, were on their way to a country alongside the South China Sea and a war with an increasingly voracious appetite for the lives of young Americans. Two young men from Boston, Massachusetts, teenagers still, suddenly found themselves in Quang Tri Province, South Vietnam.

“Me and Sonny thought they’d keep us together,” Ernie Washington recalled. “They didn’t. We got to DaNang and we got assigned to different units.”

In late July 1967, Washington and a few other members of his squad, all of them wrapped into Charley Company, 1st Battalion, First Marines were hearing about riots lighting up Detroit, claiming 43 lives before being brought under control, a great American city reeling in flames and violence. A letter from home arrived, Ernie’s sister writing to him, hoping he was fine, praying he was okay, heartbroken over Sonny.

“I didn’t know,” Ernie Washington was saying. “Like I said, we got separated at DaNang. Found out in a letter from my sister.”

Sonny Davis had been killed on July 7, 1967. Died up on the DMZ, the demilitarized zone separating the then North from the South in Vietnam. He was 19 years old, the only child of Bubba and Lena Davis, the best friend and blood brother of Corporal Ernie Washington.

“My whole world changed after I read that letter,” said Ernie Washington. “Then what happened when I finally got home…well, that’s still with me today. Still with me.”

On the evening of April 4, 1968, Corporal Washington landed in Boston, Massachusetts, his tour of duty nearly at an end. He had stripes on his sleeve and a Purple Heart on his chest as he carried his seabag on his shoulder, marching through the terminal at Logan Airport. Martin Luther King had been assassinated in Memphis earlier in the day and Boston, like many other cities, was in the throes of violence.

“I tried to get a cab home,” he remembers. “One, two, three cabbies stopped but when I told them I was going to Roxbury they told me ‘No way.’ I walked to the bus station but even the bus would only go so far. I ended up walking most of the way home. I was wearing a uniform that nobody seemed to like anymore.”

Saturday, Ernie Washington listened as Barack Obama spoke quite powerfully at the edge of the Edmund Pettus Bridge. He is 68 years old now. He came home, returned to school, went to Northeastern University and Bentley College. Started his own parking business at Northeastern. Hired many young men over the years who came out of the projects and off the streets where danger, drugs, and unemployment too often combine to kill dreams and lives before they ever get to flourish.

“I was proud listening to the president,” he said. “And I was glad he said the march isn’t over. I’m old now. A lot of time has passed but I still think about Sonny most every day. I still think about Bubba Davis every day and how every time he’d see me he’d start crying. Me, reminding him of Sonny and all that.

“And I still remember not being able to get a taxi to take me home. I was in my uniform. I was a Marine and nobody would take me home. That was enough of a message for me that it has lasted a lifetime.”

Fifty years in the life of the Republic is the snap of a finger when measured in history’s terms. And while the pain of inequity and intolerance has been eased somewhat across the decades, Ernie Washington and millions of others march onward today knowing a long road still lies ahead of those seeking to cross a bridge to justice.