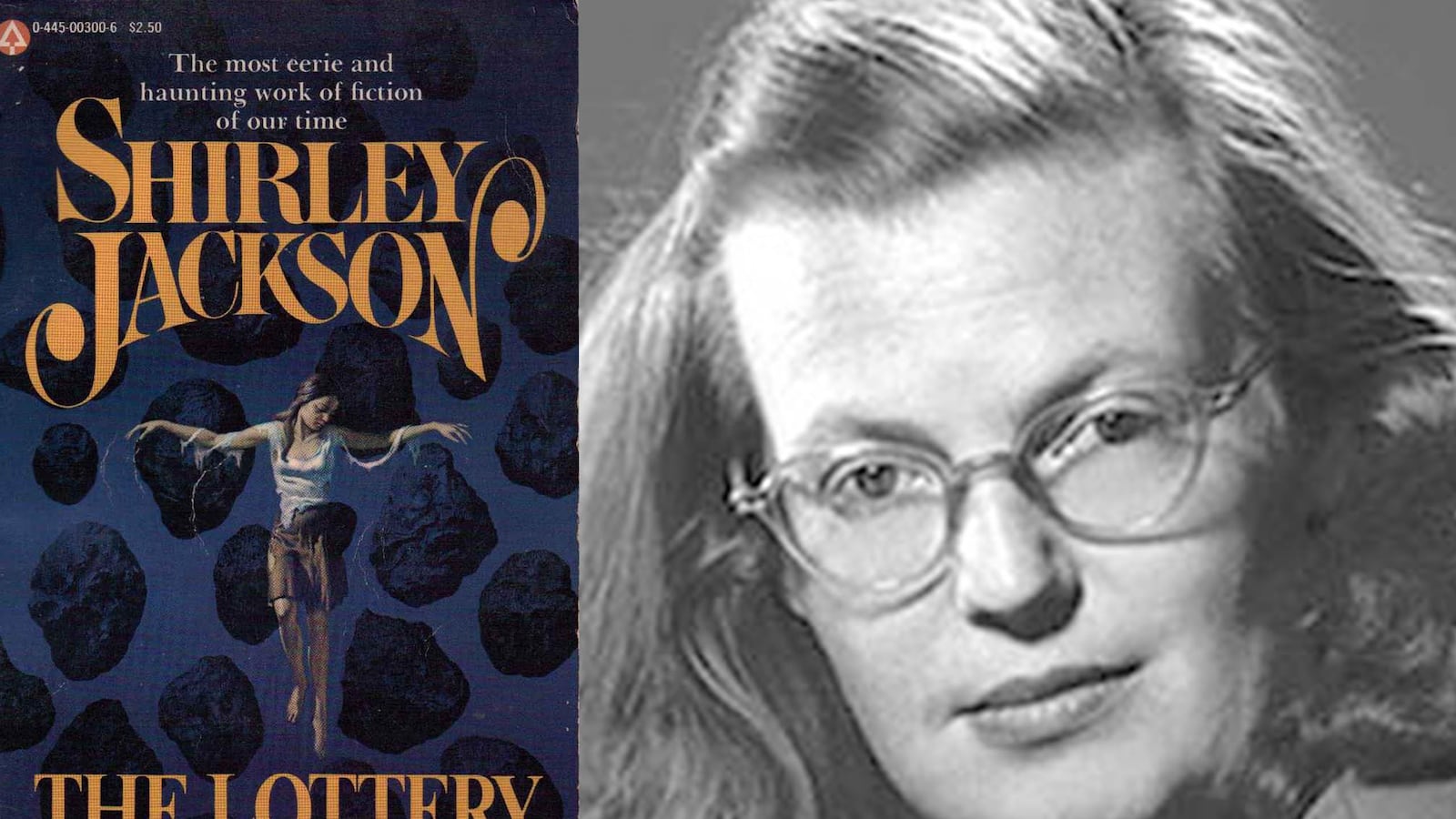

Most people are familiar with the horrifying twist-ending short story “The Lottery,” which they were forced to read in freshman English class in high school, never to fully recover.

The story, published by The New Yorker in its June 26, 1948 issue, remains one of its most provocative pieces of fiction—after its publication, the magazine received more letters and phone calls in response than ever before, or ever since. Its author, Shirley Jackson, collected all of the correspondence, much of it hate mail. Though she said that if the letters “could be considered to give any accurate cross section of the reading public… I would stop writing now,” I would wager to guess that she came to cherish its infamy. Or, at least, I hope she did.

“The Lottery” eventually became part of a larger collection of short fiction published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, also in 1948, entitled, The Lottery, or, The Adventures of James Harris. Wait. James who?

The sad fact of the matter is, you’ve probably never read the collection in which “The Lottery” resides. (If you have, major kudos.) You should read the whole collection in its entirety. In addition to the excellent “Lottery,” there are several other fine stories that will absolutely chill you to the bone. And this James Harris appears in over half of them. One could argue that he is present, though perhaps not mentioned explicitly by name, in all of them. Jackson’s “The Lottery” is a thematic collection of short fiction. In other words, all the stories in this collection are linked.

We first meet James Harris in “The Daemon Lover,” in which a woman is readying for her wedding day to James when he mysteriously disappears, leading her to search the entire neighborhood for a tall man in a blue suit, as she describes him. In the next story, “Like Mother Used to Make,” Mr. Harris appears again, this time as an uninvited dinner guest. To say he overstays his welcome is an understatement. In several stories he’s described as a writer—or describes himself as a writer. In “A Fine Old Firm,” he’s a lawyer. In “Seven Types of Ambiguity,” he is the owner of a bookstore.

He often appears to make suggestions, in particular to those in distress. In “The Witch,” he appears in a slightly older form: “He was an elderly man with a pleasant face under white hair; his blue suit was only faintly touched by the disarray that comes from a long train trip.” A young woman, delirious from a bad toothache and on her way to the dentist in the city, meets Mr. Harris on the bus. “The grass is so green and so soft,” he says to her as she falls in and out of consciousness, “and the water of the river is so cool.” In “Got a Letter From Jimmy,” a woman’s husband refuses to open his letter from his friend Jimmy, driving his wife absolutely mad. “Under the cellar steps,” she thinks, “with his head bashed in and his goddam letter under his folded hands, and it’s worth it, she thought, oh it’s worth it.”

Even when we meet Mr. Harris in “Of Course,” through a third party, his wife, his presence is undeniable. Mrs. Harris explains her husband doesn’t allow for movies, television, radio, or even the newspaper in his home. “You’ll be thinking my husband is crazy,” she says to her new neighbor, Mrs. Tylor.

“Mrs. Tylor recognized immediately the faint nervous feeling that was tagging her,” Jackson writes. “It was the way she felt when she was irrevocably connected with something dangerously out of control: her car, for instance, on an icy street, or the time on Virginia’s roller skates…”

And just in case you still had any questions about the identity of Mr. Harris, Jackson closes the collection with an epilogue, the complete text to a popular Scottish ballad called “James Harris, The Daemon Lover,” about a man, presumed to be the Devil, who returns to his lover and convinces her to leave her husband and child and come with him to Hell by way of the sea. (This sounds eerily familiar from what Jim says to the woman with the bad tooth.) Jackson also begins certain sections of the collection (which, by the way, is dedicated “to my mother and father”) with a quotation from Joseph Glanvil’s Sadducismus Triumphatus, a book on witchcraft, published in 1681.

It shouldn’t come as any surprise that the stories in the collection share this theme—the presence of total and absolute evil in daily life, in fact, the presence of the Devil himself—but why is there no discourse on the collection as a whole? Perhaps “The Lottery” itself is to blame. The shock value of that single story made Jackson’s name, but also unfortunately managed to eclipse her other work.

Even in the very first story in the collection, “The Intoxicated,” we can find James Harris, though his name is never mentioned. At the end of the party we see the hostess “deep in earnest conversation with a tall, graceful man in a blue suit.” As it turns out, Jim Harris, like Jackson’s genius, was always there. That is, if you know where to look.