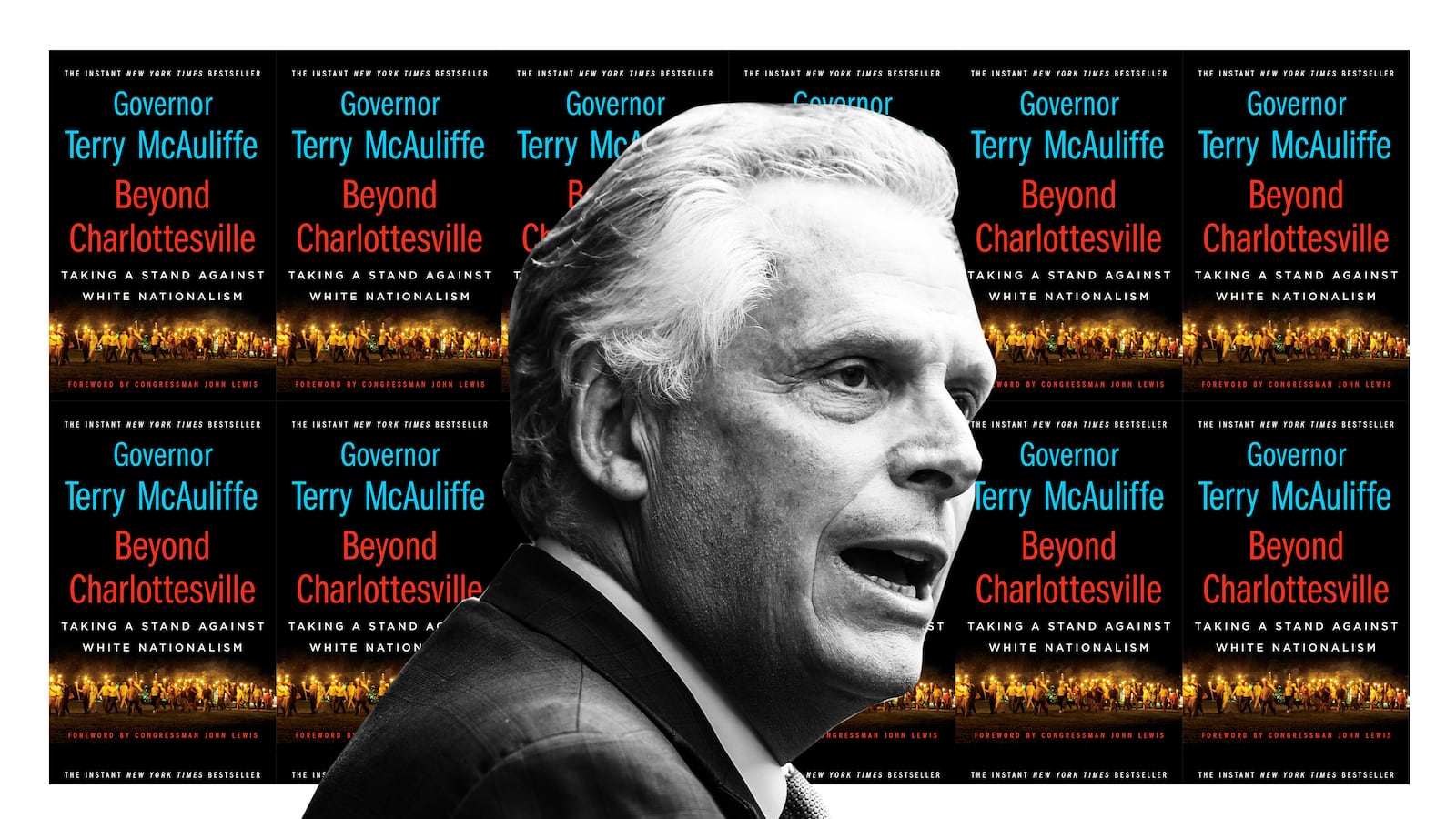

Former Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe’s new book, Beyond Charlottesville, tries to tackle the issues of white supremacy that resulted in a deadly neo-Nazi rally in August 2017. But the book isn’t a hit with everyone in its namesake city.

Beyond Charlottesville centers on Unite the Right, the 2017 white supremacist rally where a neo-Nazi drove his car into a crowd of anti-racist protesters, killing one. Two state troopers also died in a helicopter crash while monitoring the rally. Activists and independent investigators criticized the police response to the rally, claiming that miscommunications between a variety of police forces allowed the event to devolve into violence. McAuliffe’s book omits context about the bureaucratic chaos—and at points is outright wrong, critics say.

“The book is about racism and white nationalism, the rise of it in the country,” McAuliffe told The Daily Beast. “I talk about the issues we’ve had in Virginia. As I always say, horrible as Charlottesville was, the one benefit was it did rip off the scab on racism and we need to have a frank discussion.”

But some survivors of the Unite the Right car attack say McAuliffe’s version of the story isn’t completely frank. Some of those survivors have interrupted McAuliffe’s book talks, including an event at D.C.’s Politics and Prose earlier this month.

“The story he’s telling in Beyond Charlottesville is ahistorical. It’s not accurate,” Anna Malinowski, one of the protesters, told The Daily Beast.

A report this week in Charlottesville’s Daily Progress, the city’s sole daily newspaper, highlighted some of the inaccuracies, from small factual errors, to larger issues of framing.

In Beyond Charlottesville, McAuliffe says he “knew without a doubt that we’d done everything we could at the state level to prepare for Charlottesville, but obviously somewhere in the implementation and coordination, those plans went off the rails.”

But, as the Daily Progress noted, an official Charlottesville investigation revealed a high level of dysfunction at the local and state levels, including miscommunication between local and state police forces during the rally.

The Progress also took issue with McAuliffe’s explanation for why it took so long for state officials to declare a state of emergency. (McAuliffe wrote that he was waiting for the city to declare an unlawful assembly, which in fact they had declared during the previous night’s torchlit march, and again on the rally’s second day, in addition to a local state of emergency.). In the book, McAuliffe also describes calling Charlottesville’s then-mayor Mike Signer and recommending he ban guns from the rally area, a move Signer could not legally make.

Signer objected to elements of the book in his own op-ed for the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “It’s well-written and contains a powerful personal condemnation of white supremacy that deserves attention. However, it also contains errors and omissions,” Signer wrote, accusing McAuliffe of shifting too much blame onto the city.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Virginia released a similar critique.

“Governor McAuliffe’s book is yet another example of a politician’s effort to pass the buck of responsibility when there was a clear failure of leadership,” the ACLU of Virginia told the Progress in a statement. “The leaders had ineffective and uncoordinated plans for managing the protest.”

Survivors and investigators blamed some of the day’s chaos on poor police coordination between too many agencies.

“They pretty much brought in the cavalry when they found out there would be a lot of white nationalists there. There were Virginia State Police, there were National Guard, there were city and county police,” Malinowski, who narrowly avoided being hit by the car, said. “There was lots of fighting going on that was incited by the white supremacists, and the police basically did nothing either to prevent it or stop it while it was happening.”

At the D.C. protest this month, Malinowski and other protesters accused McAuliffe of “using black folks as political currency” and not paying attention to what they say are white supremacists in law enforcement.

They also objected to McAuliffe’s plan to donate some proceedings to the Virginia State Police Association. This last point is of particular contention between the former governor and the Charlottesville activists.

At least one person at the D.C. protest chanted “cops and Klan go hand in hand,” a slogan popular among some activists on the left. They mean some of the chant literally (a number of law enforcement officers have been found to have white supremacist ties) and some of it more figuratively, in the context of police brutality against people of color. (After Unite the Right, many Charlottesville locals turned an eye to stop-and-frisks by the city’s police, which disproportionately affect minorities in the city.)

McAuliffe’s book also addresses structural racism. But he said the chant was beyond the pale.

“They call the KKK and the police the same thing and that, to me, is very disrespectful to all law enforcement,” McAuliffe said. “Everybody had the same goal that day, and it was to keep everybody safe. But to call police the KKK is highly offensive, highly disrespectful.”

Malinowski and others said the money would be better spent on survivors, some of whom have struggled to pay medical bills, or to make rent after injuries from the car attack pushed them into unemployment. Matthew Christensen, who recently served as an advocate for victims of the attack, said the problem is the result of a complicated victim support system, which sees many survivors relying on a private victims’ fund called Heal Charlottesville.

“I have a Master’s in social work,” Christensen said. “Some of the bureaucracy we were working with was difficult for me. For anyone else, especially people dealing with trauma, it’d be exponentially more difficult.”

Survivors can technically apply for a state fund that compensates victims of crimes. But that system only pays out in cases of “last resort,” and has redirected survivors to the Heal Charlottesville fund. As of June, the fund had expended all its funds, a spokesperson told The Daily Beast.

Since the protests, McAuliffe said he would split the book’s proceeds between the police association, the Heather Heyer Foundation (as originally planned), and the Heal Charlottesville Fund.

“I say to anybody: if you’ve got outstanding bills, all of us—the whole community, the whole state —ought to be involved in assisting,” he said. “We reached out to a couple of the groups, which is somewhat surprising to me because the main one, [the administrators of the Heal Fund], said they have a surplus left and they have no claims in front of them.”(The Heal Fund told The Daily Beast it does not have a surplus, although it has secured money for survivors’ ongoing claims.)

McAuliffe said his book was especially timely as President Donald Trump launches Twitter attacks against legislators of color.

“It’s a very opportune time to have this big discussion on where we go as a nation, because we are so split today as a country,” he said. “The hatred and the racism and what’s going on in the country today needs to be addressed and we need to have a conversation. We need elected officials to do something about it.”

Malinowski, meanwhile, said the book was too late.

“The only thing he should be saying is ‘I messed up, I should have done more to protect these people,’ and he’s not saying that. He’s trying to be the hero in his book.”

Editor's note: this story has been updated to clarify the recipients of McAuliffe's book proceeds.