The loose ensemble known as the “New Atheists” have always had a weirdly evangelical streak, with their emphasis on faith as the essence of religious practice, and with their implication that the entire world would be better off if everyone would start thinking exactly as they do. It was inevitable, then, that the movement would eventually produce something like A Manual for Creating Atheists, Peter Boghossian’s new guide for atheists who wish to proselytize the faithful. Equipped with a foreword by Michael Shermer entitled “Born-Again Atheist,” Boghossian’s book formalizes that missionary streak. The result has all the passion, tact, and nuance of a street-corner preacher.

Don’t believe me? Try to identify which of the following are Billy Graham quotes, and which are taken from A Manual for Creating Atheists:

1. “…a lot of people feel some religious belief in their hearts, Buddhists, Muslims, Mormons, people who think the Emperor of Japan is divine. But they can’t all be correct.”

2. “Truth does not differ from one age to another, from one people to another, from one geographical location to another.”

3. The goal of this book is to create a generation…who actively go into the streets, the prisons, the bars, the churches, the schools, and the community…”

4. “It makes me feel awesome…What would it take for you to open yourself up to that gift?”

5. “I feel sorry for the man who has never known the bracing thrill of taking a stand and sticking to it fearlessly. Moral courage has rewards that timidity can never imagine.”

6. “There is no other way [to arrive at the truth].”

Numbers 2 and 5 are Graham. The rest are Boghossian.

Boghossian, who teaches philosophy at Portland State University, is upset because so many people view the world through the lens of faith, which he considers “an unreliable epistemology.” Drawing on the Socratic method, Boghossian develops a set of tools for “Street Epistemologists,” who, in his vision, will engage complete strangers and undertake “clinical interventions designed to disabuse them of their faith.” Muscular atheism has arrived; “left behind is the idealized vision of wimpy, effete philosophers.”

Boghossian instructs atheists to ask leading questions to guide the believer toward moments of uncertainty. Like Socrates, Street Epistemologists are to understand themselves as inquisitive teachers, not combative lecturers. “Avoid politics,” Boghossian advises. “Don’t rush.” Keep in mind that “a pregnant pause is a very useful, nonthreatening technique.” “Express empathy,” but expect resistance: “Street Epistemologists should prepare for anger, tears, and hostility.”

Wisely, Boghossian advises missionary atheists against attacking God and, in particular, religion. “In church, for example, many people make new friends, play bingo in community halls, engage in casual sports with a team, sing songs with their friends and with strangers, date, etc.,” he writes with the tender bafflement of an anthropologist transported to1950s Omaha. Because bingo and bingo-like activities are harmless and fun, Boghossian urges atheists to focus instead on the problem of faith.

By his own accounts, Boghossian is a veteran Street Epistemologist. In one scene, he wanders around a church looking for faith-infected victims to cure. At the gym, he quizzes the Christian jogging on the neighboring treadmill about the nature of subjective experience. Socratic dialogue during strenuous exercise: take that, effete philosophers! In a recent interview, Boghossian explains that every time he goes to the bank, he looks for a particular teller who “wears a cross, and every time I see her I go out of my way to wait in her line, and I immediately begin the intervention.”

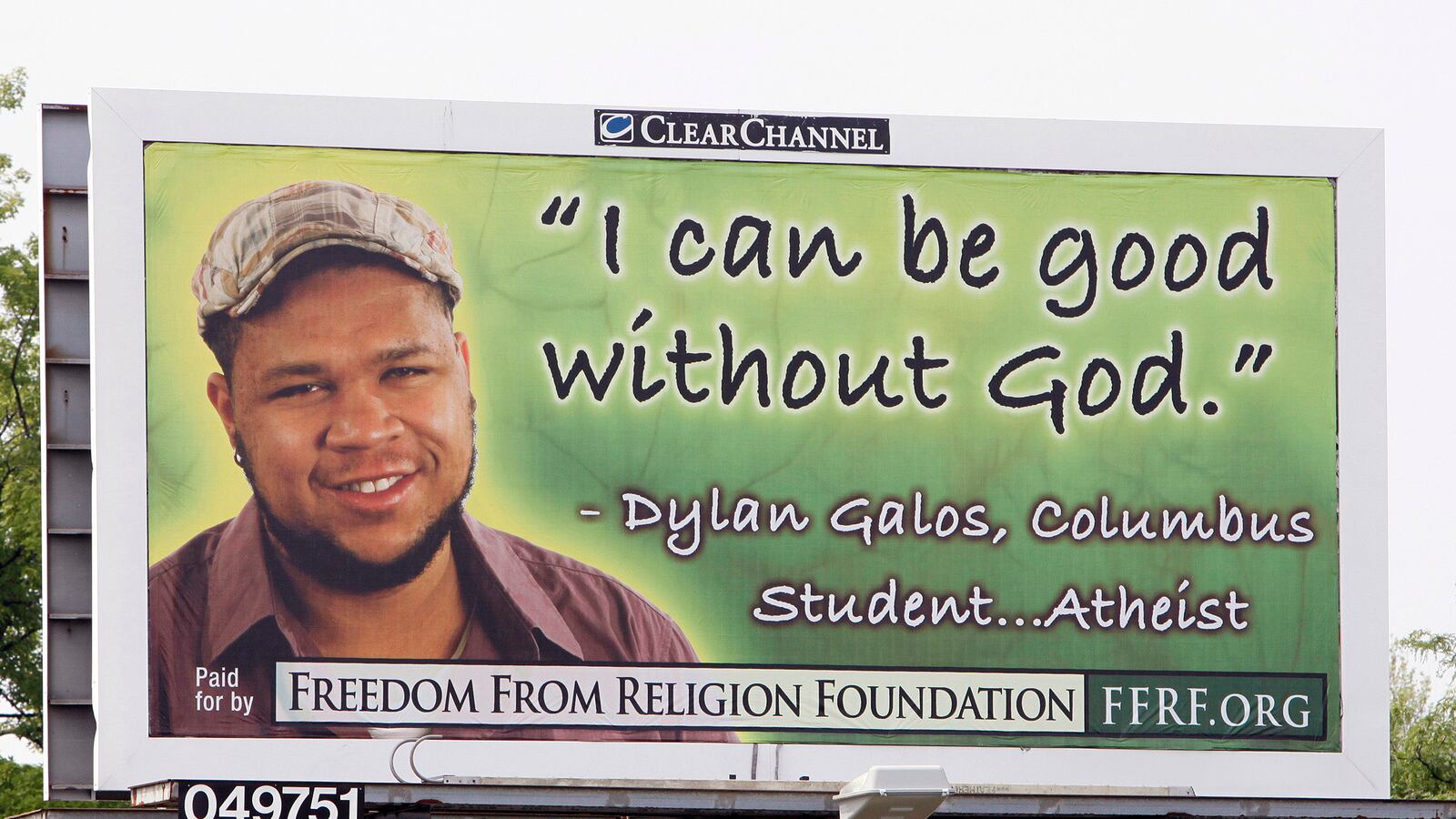

Few atheists go to such extremes. But Boghossian is hardly an isolated voice. His book has endorsements from a number of prominent atheists, including Shermer, Richard Dawkins, and the University of Chicago biology professor Jerry Coyne. “Since atheism is truly Good News, it should not be hidden under a bushel,” writes Dan Barker, co-president of the Freedom From Religion Foundation, in his endorsement of Boghossian’s book. For this small but high-profile representatives of activist atheism, the word of no God is a new gospel—one that’s eager to condemn those who don’t embrace its message.

Like other New Atheists, Boghossian’s efforts are directed toward convincing religious believers that there are more effective methods than faith for reaching factual absolutes—as if the goal of faith, for all believers, were empirical accuracy. In this vein, Richard Dawkins attacks the “God Hypothesis” as if God were a scientific proposition. “Faith claims are statements of fact about the world,” Boghossian argues—or, more accurately, asserts, since he offers no actual support for this central claim.

As far as I can tell, there are only two groups of people who consistently evaluate religious postulates and scientific facts on the same terms: certain members of the fundamentalist fringe, and New Atheists. Both of these groups struggle to understand that most believers do not see their faith as strictly factual—that the kind of knowledge they seek in a church or a mosque and the kind they seek from a lab might not be quite the same. Even when confronted with a powerful personal experience of what the non-rational has to offer, Boghossian can’t accept that there’s anything legitimate beyond his clinical empiricism. When, in one of the book’s most thoughtful, moving scenes, Boghossian describes his mother on her deathbed, clutching a statue of Jesus, he expresses mild surprise that he could not bring himself to challenge her delusions.

Though many religious people accept that faith can’t be articulated in scientific terms, many of them, at least when under questioning from a philosophy professor, will try to rationalize their beliefs. Boghossian’s proselytizing tactics—which he illustrates in a number of stilted real-life dialogues—work by pressuring believers to translate their beliefs into the language of empirical rationalism, and then pouncing on them when they fail. And they do fail, of course, but the whole exercise is a bit like bringing literary scholars to a chemists’ convention, asking the literati to explain which novel demonstrates the best experimental methodology for arriving at truth, and then tearing them to shreds when they offer a discombobulated explanation in favor of Finnegan’s Wake. The two kinds of inquiry just aren’t aiming for the same kind of knowledge.

This might sound like bland cultural relativism: we’re all right, in different ways! But no spineless relativism is necessary to recognize that, for most human beings, realness comes in various flavors. The weirdness of the New Atheists is not that they advocate for scientific rationalism—which is, in fact, a remarkable, and for many purposes unparalleled, way of viewing the world. It’s that they advocate for scientific rationalism as an exclusive method for perceiving the world.

As a result, we can see in the writing of Dawkins and Sam Harris, and certainly in A Manual for Creating Atheists, a disdain for the whole idea of a pluralistic society—a disdain, tellingly, that they share with conservative evangelicals. Boghossian, in the book’s final chapter, argues that the faithful should be politically marginalized and perhaps even considered mentally ill. It’s frightening to imagine a society in which there’s only one sanctioned method for evaluating the world. (Theocracy, anyone?) Frustrating as our national discourse can be, the checks-and-balances of a pluralistic society certainly seems preferable to that.

Movements don’t radicalize when they start having crazy ideas. Movements radicalize when their members become unable to have ordinary interactions with people different from themselves. We need strong, persuasive secular voices, who can explain the power and advantages of non-belief, and draw intelligent comparisons between their own ways of seeing the world and the ways of faith. If A Manual for Creating Atheists has any moral, it’s that New Atheists run the risk of becoming a reflection of that which they most despise.