The HBO docuseries Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children asks us to question not only the legitimacy of the U.S. legal system and law enforcement, but also the racial and class dynamics that underpin those very institutions and heavily influence the public’s ideas about guilt and innocence.

The series, produced and directed by Sam Pollard, Maro Chermayeff, Jeff Dupre, and Joshua Bennett, establishes an intense and largely ignored history that has defined the city of Atlanta ever since: Between 1979 and 1981, at least 30 children (several under the age of 15) and young adults were murdered in Atlanta. They were all black and poor. At the time, Atlanta’s black middle and upper-middle class was thriving. The city’s first black mayor, Maynard Jackson, had just been elected, the music industry was on the uptick, and the Atlanta International Airport was becoming a lucrative international hub. None of this good fortune, wrought by the sweeping mechanisms of government-aided capitalism, were trickling down. In fact, poor black people lived in a world of their own, entirely disconnected from the black middle class, and were much more likely to cross paths with poor and working class white communities on Atlanta’s outskirts.

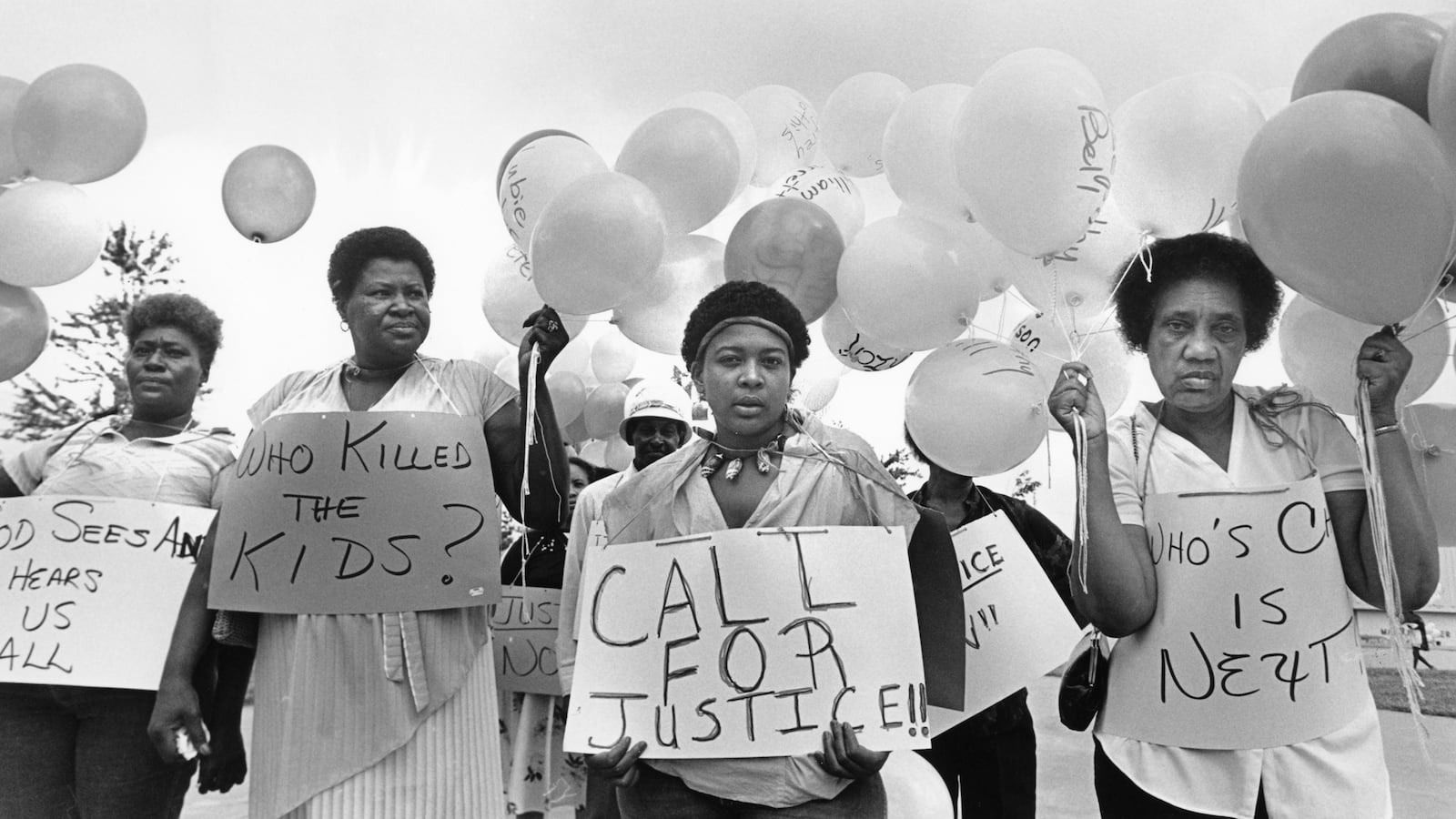

Since this is Georgia we’re talking about, some of those white folks were Ku Klux Klan members, or even ran with more extreme groups like the National States’ Rights Party, which openly promoted more physically violent methods of sustaining white supremacy. As one former Atlanta police officer in the documentary points out, during the mid-century at least, much of the police force was Klan. When the children began to go missing in 1979, and later, when their bodies began turning up, dumped in the woods and abandoned buildings, the families of the missing and murdered—especially the mothers—felt intensely that the Klan and their ilk were behind it.

Instead, the FBI—who came in years later thanks to the pressure of a committee of poor black mothers headed up by Camille Bell, who had lost her son Yusuf—found a 23-year-old middle class black man who seemed to have connections to several of the murdered children based on fibers FBI forensic scientists found on the bodies and traced back to his house, and fit a profile the FBI had developed based on certain assumptions and “experiments” they ran on the ground. This man is Wayne Williams, who is currently serving two life sentences for the murders of the last two accounted-for victims, Nathaniel Carter and Jimmy Ray Payne, who were 27 and 21, respectively. The FBI refused to pursue the rest of the 30 cases after Williams was convicted, even though they had several other suspects—including a pedophile ring and KKK members—and plenty of information in conflict with the evidence against Williams. Williams maintains his innocence, and revelations from a former FBI forensic scientist whistleblower (who participated in the documentary) has since thrown much of the FBI’s case against Williams into doubt.

Still, the many FBI agents who worked on the case also participate in the documentary and staunchly defend their work and castigate Williams, calling him a sick monster who was surely capable of murdering and then swiftly disposing of the bodies of two much larger men. The series reveals the identities of several other credible suspects whom the FBI failed to arrest, and the filmmakers even dare to question the agents’ logic and reasoning about the case, bringing to light the unscientific sense of absolute certainty much of law enforcement not only prides itself on, but actively rewards and requires. And it’s not just white FBI agents, plenty of middle and upper class black people—police officers, judges, and government officials—were complicit or even directly involved in the blunt authoritarianism that oversaw the Atlanta child murder cases.

Georgia State professor, lawyer, and scholar Natsu Taylor Saito, another docuseries participant, tells the filmmakers that her partner, Chimurenga Jenga, a black U.S. Marine Vietnam vet who was disillusioned by the Atlanta he returned to, created a Black Panthers-esque community militia to protect the children. He and other militia members were later arrested by local police for open carrying—local news called them “vigilantes”—and the series ominously does not reveal what became of Jenga after his arrest. In raising the daughter she had with Jenga, Saito—who is Japanese-American and indigenous—was forced to internalize a kind of paranoia for her family’s survival. Her testimony, along with that of Williams’ defense teams and some of the local government officials, are the only ones that question official narratives about the case and community dynamics that went on around them. The FBI and local police instead paint a picture of a broken community of child hustlers and bad mothers who essentially had it coming.

Camille Bell, the mother who fought to bring recognition and justice to the mothers and children of poor black Atlanta, is a recurring figure in the series, though only via the archive. Her brilliant media appearances and fierce community organizing left an indelible mark on the city before she was essentially driven out by the politics and power that was. Her voice, along with those of the mothers and siblings who directly appear in the docuseries, are the most credible because they speak not only from the experience of the children’s deaths, but from lifelong experiences of extreme government negligence and profound intergenerational knowledge that those charged with solving the cases refused, and still refuse, to witness.

Today, the current Atlanta mayor, Keisha Lance Bottoms, has tasked her administration—as well as Atlanta police—with thoroughly investigating the 20-odd cases that the Feds left cold. It’s unclear whether the investigation is just a dog-and-pony show conceived to score political points, or if it is a legitimate inquiry that could actually give the still-grieving families answers about who harmed their children. These families, by and large, doubt that Williams is responsible, though many admit that they don’t know either way—like Williams, they are simply asking for a fair trial. Under the current and enduring system, it’s unclear if such a thing could happen.