Geologists are not generally all that excitable. After all, developments in their field generally take place over millions of years. But when scientists began scouring the Atlantic off southeast Brazil in 2011, they suspected that they were on to something—and something very big, at that.

Two years—and half a dozen deep-sea expeditions later—the geological world is abuzz. Brazilian marine geologists are poring over the rubble dredged up from the undersea excavations in the so-called Rio Grande Elevation, and the research done by a Japanese exploration vessel, which deployed a mini, three-man submarine to comb the same waters before sailing on to Rio.

So what did the rubble reveal?

This week, a joint Brazilian-Japanese research team broke its long silence, officially unveiling its find with a head-turning and slightly mischievous teaser: Could this be a “Brazilian Atlantis?”

“Today we believe we may have found vestiges of an unknown continent,” Roberto Ventura Santos, head of the Brazilian Geological Service, told The Daily Beast. The evidence? Not gold but granite. “We expected to find volcanic rock and debris, typical of a seabed, not granite. Granite is typically found on the continental shelf.”

And yet, as Santos pointed out, this was 1,800 miles from the Brazilian shore, where the water is 5,900 feet deep.

No one in Rio or Tokyo expects to find traces of human life on the ocean floor—never mind the ruins of the iconic Atlantis of Plato’s prose: an island where the marine god Poseidon is fabled to have lined his palaces with gold and silver and where elephants and “wild beasts of prey” roamed.

However, if the scientists’ hunch pans out, they will have stumbled upon the earth scientists’ equivalent of hidden treasure. Proof of an underwater continent could be a major piece of a geological puzzle allowing scientists to reassemble events of literally seismic proportion that stretch back tens of millions of years.

The geologists’ Atlantis is a glimpse into the geological upheaval that around 200 million years ago created our world as we know it. The earth shrugged and shifting tectonic plates forced the supercontinent Pangaea to break apart to form the African continent in the east and South America to the west.

Researchers now believe that the high plateau in the high seas might just be a sunken remnant of that earth-moving event. And with this discovery, for the first time, scientists have what could be their best chance to test the theory in the field.

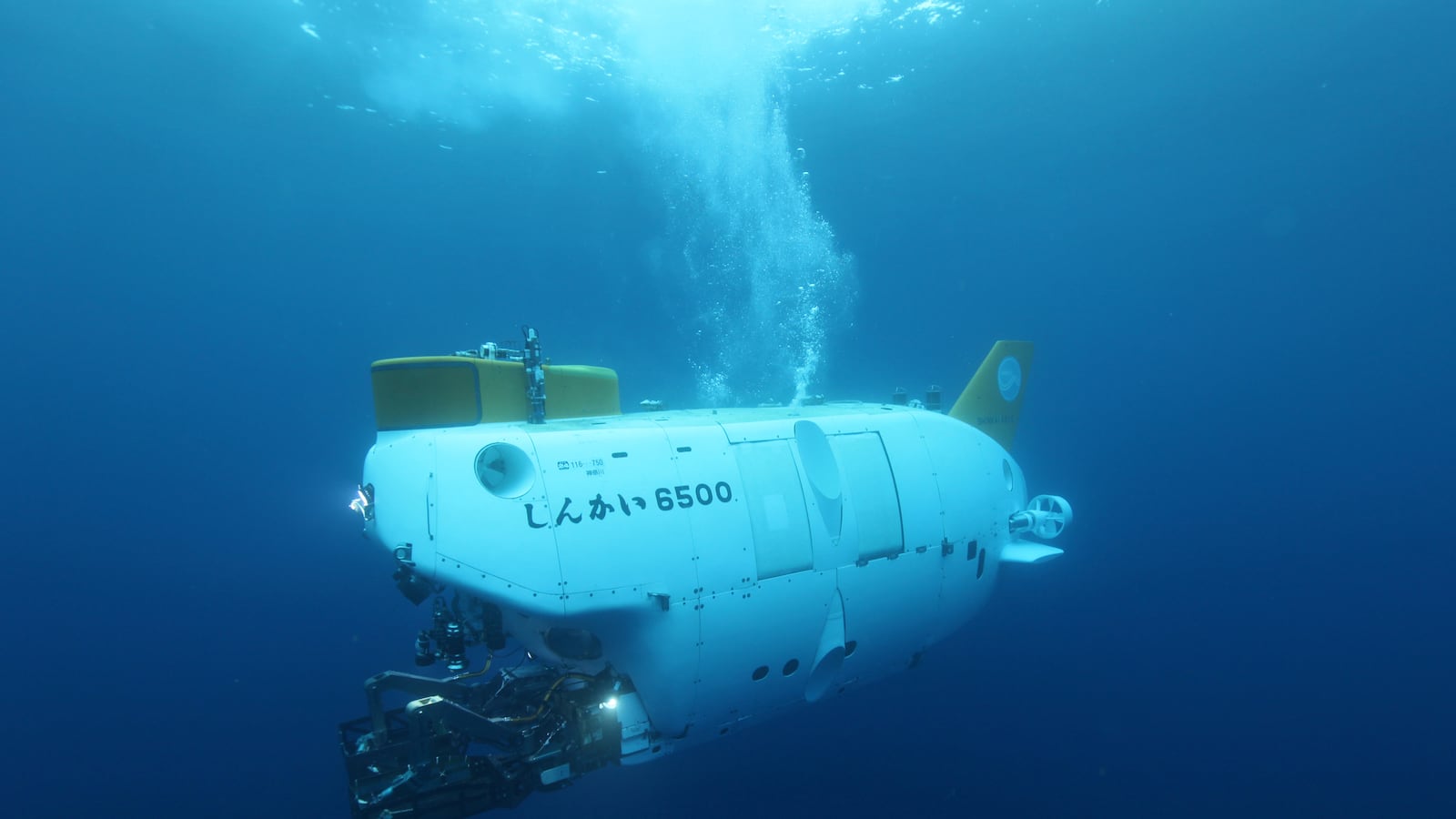

After the Brazilian research vessel searched the bed of the Rio Grande Elevation, the Japanese submersible Shinkai moved in for a closer look. Designed to descend up to 21,300 feet and withstand crushing water pressure 500 times greater than at the surface, the rugged mini-sub took seven different dives during which the crew photographed and took measurements across the massive underwater plateau. They found irregular, craggy peaks and valleys, with one underwater mountain rising some 9,800 feet from the ocean floor. The next step will be extensive drilling by a giant pile driver device that will pull up core samples from across the submerged plateau.

This is not the first time science has gone searching for lost worlds. Ventura is reading everything he can on similar expeditions, including the recent find in the Indian Ocean, where geologists have dredged off Mauritius, near Madagascar. “There they are looking over traces of zirconium silicate [another mineral found in the continental shelf] mixed with sand. The difference is we have found solid rock.”

Ventura said the fragments of granite retrieved from the Rio Grande Elevantion are more direct evidence of a possible continental landmass. “This could be our smoking gun,” he said.

But since science is a slippery vocation, Ventura is holding his enthusiasm on tight reins. “There is the possibility that the granite could be a chunk of ballast from a sunken ship,” he said, though acknowledging that the chances of dredging up a scrap from a shipwreck a mile below the ocean’s surface seem improbably slim. “We need to look closer.”

Ironically, the Brazilians had no intentions of finding a continent in the middle of the Atlantic. Rather, the geologists set sail a few years ago as part of a government plan to boost growth by building research capability and offshore technological know-how. Both skill sets would come in handy as the country ramps up to exploit its offshore oil, the 50 billion to 80 billion barrel cache of crude oil recently found in ultra-deep waters of the Atlantic.

The Brazilian Geological Service teamed up with the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), which was drawn by the fact that this stretch of the Atlantic is one of the least explored of the world’s ocean regions.

The fact that the Rio Grande rise also harbors traces of iron and manganese was not lost on the minerals industry. With some of the world’s biggest onshore reserves of minable minerals, like iron, gold, nickel, and manganese, Brazil is not yet part of the blue-water gold rush. But the global scramble for natural resources is already driving mining from the mainland to the ocean floor.

So far, it is science, not mineral stakes that motivates geologists like Ventura. “The oceans are where life began,” he said. “If this proves to be an unknown continent, we can possibly simulate how life on the planet evolved.”