No matter what you call them, extremist religious groups led by charismatic gurus are rarely to be trusted. Japan learned that lesson the hard way on Mar. 20, 1995, when a sarin gas attack on Tokyo’s subway system left 13 people dead and hundreds injured.

That a chemical weapon created by the Nazis had been used against the public was hard to stomach. Even tougher to comprehend was the fact that the terrorist perpetrators were the victims’ own countrymen: followers of a high-profile collective known as Aum Shinrikyo, which promised acolytes supernatural powers, preached about the coming apocalypse, and threatened enemies with death.

Premiering at this year’s Sundance Film Festival in the U.S. Documentary Competition, Ben Braun and Chiaki Yanagimoto’s sharp and unsettling directorial debut AUM: The Cult at the End of the World is a non-fiction adaptation of journalists Andrew Marshall and David E. Kaplan’s similarly titled book, and an incisive look at the inner workings—and rise to prominence—of Aum Shinrikyo, an outfit whose origins were, on the face of things, humble.

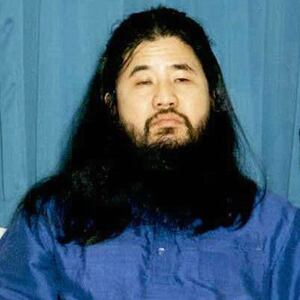

Founded as a yoga school, Aum Shinrikyo was the brainchild of Shoko Asahara (real name: Chizuo Matsumoto), who in 1987 transformed his fledgling venture into a legally recognized religion. To promote Aum Shinrikyo, he produced books and anime cartoons that spread his gospel, which at first was most notable for proclaiming that adherents would attain the same powers he had: namely, the ability to read people’s minds and levitate.

To explain why Asahara’s teachings proved so appealing to young Japanese, AUM: The Cult at the End of the World contextualizes Aum Shinrikyo as a byproduct of various socio-political factors.

By the conclusion of the 1980s, the country’s economic good fortune was wavering, thereby resulting in a negative view of materialistic success and financial growth. With the nuclear arms race between the U.S. and the USSR spawning doomsday fears, a pessimistic outlook about the future took hold, giving birth to an “occult boom” full of conspiracy-theory fantasies about aliens, reincarnation and impending Armageddon. It was in this environment that Aum Shinrikyo emerged, and according to the film, it turned out to be particularly attractive to men and women who’d been raised by parents who were damaged, dysfunctional members of the World War II generation.

Aum Shinrikyo soon captured the spotlight, thanks in part to its practice of indoctrinating recruits and then cutting them off from their families, who invariably sought them out while accusing the organization of brainwashing their kids. Eiko and Hiroyuki Nagaoka were two such parents. In response to their son joining (and disappearing into) Aum Shinrikyo, they formed the Aum Shinrikyo Victims’ Association, and partnered with attorney Tsutsumi Sakamoto to get some answers about the group (including by filing a class-action lawsuit).

What they came to realize, however, was that in a country with a history of suppressing freedom of religion, no one wanted to be critical of Aum Shinrikyo; on the contrary, many were intent on bolstering the cult’s image by having them on TV programs, where they could present themselves as innocent, cheery and entertaining—something Asahara is seen successfully accomplishing on Takeshi “Beat” Kitano’s talk show.

Even when Sakamoto and his wife and baby son went missing shortly after a television appearance opposite Asahara, police put minimal effort into investigating Aum Shinrikyo. Asahara proceeded to create a political-party offshoot of the cult and mounted a costly campaign to get himself and 24 disciples elected to public office.

When that failed, however, his sermons took a darker fire-and-brimstone turn, all as he sought to extend the group’s reach into Russia via the aid of spokesperson and right-hand man Fumihiro Joyu. Though he participates in AUM: The Cult at the End of the World, Joyu doesn’t confess to being an active accomplice to Asahara’s ensuing madness, but many others point a damning finger in his direction, given his role in helping Aum Shinrikyo combat critics, recruit former Soviet scientists to their mission, and strive to acquire weapons of mass destruction.

A strange 1994 sarin gas incident in Matsumoto, coupled with the discovery of the same chemical near Aum Shinrikyo’s Kamikuishiki headquarters at the base of Mount Fuji, eventually turned up the heat on Asahara, who responded by manifesting the very end-of-days calamity he’d been predicting.

The Tokyo subway attack, and the attempted assassinations of critics that ensued, confirmed that Asahara was a madman intent on waging war against his own nation, whom he blamed—along with his parents—for his childhood abandonment, neglect and marginalization. Driven by interviews with Marshall, Kaplan, Joyu, Eiko, and Hiroyuki Nagaoka, and additional journalists and lawyers, AUM: The Cult at the End of the World affords a detailed analysis of the causes of Asahara’s popularity, and the deeply rooted hang-ups that drove him to order the infamous assault—as well as numerous other crimes.

Asahara was the primary person to blame for the offenses committed by his organization. Still, directors Braun and Yanagimoto don’t let others off the hook, in particular a police force that was too chummy with Aum Shinrikyo to do its job properly, and a media and pop culture that thought it better to coddle and advertise than to scrutinize.

There are multiple moments throughout this saga when a little bit of inquisitiveness, and a little less coziness, would have stopped things from spiraling out of control. Yet by cannily exploiting societal prejudices and nurturing relationships with those in positions of power, Asahara was permitted to build his fanatical empire—at least, that is, until he targeted innocent civilians on a widespread scale.

Ultimately, AUM: The Cult at the End of the World strives to connect Asahara’s campaign of alternate reality-fueled hostility to the political polarization of today, and while there are certainly links to be made, Aum Shinrikyo’s true bedfellows are the myriad other past and present cults of personality—here in America and abroad—that prey on the weak, desperate and gullible, spellbinding them with guarantees of salvation and strength if they only sacrifice everything for holy leaders and their mission. In that regard, Braun and Yanagimoto’s documentary isn’t just timely; it’s a tale as old as time.