Welcome to The Beast Files—epic adventures, real-life mysteries, and more stories you can’t put down. Become a Beast Inside member to keep reading.

Two weeks after the fall of Saigon, on May 12, 1975, Khmer Rouge soldiers on patrol boats fired a rocket-propelled grenade across the bow of the U.S. merchant ship SS Mayaguez.

The United States didn’t recognize the Khmer Rouge’s claim of 12 nautical miles of territorial waters. When the more than 10,000-ton container ship sailed too close to Poulo Wai island on its way from Saigon to Sattahip, Thailand, the patrol boats scrambled to chase it.

Owned by Sea-Land Service Inc., the Mayaguez was carrying 274 containers—77 military containers, 107 routine cargo, and 90 empty containers. The load was insured for $5 million. When the patrol boats caught up, they fired machine guns first and finally a rocket propelled grenade across the bow. The explosion sent a geyser of water into the air.

“Give me maneuvering speed,” the Mayaguez’s captain, Charles T. Miller, told the engine room, according to The Four Days of Mayaguez by Roy Rowan.

Miller, the 62-year-old merchant captain, was angry. His jaw “jutted and his nostrils flared in anger” according to Rowan’s book, as the ship slowed and the crew lowered rope ladders to the waiting patrol boats.

Just before seven Khmer Rouge soldiers boarded, Miller ordered the radio room to send an SOS. The call was received by a private company in Jakarta, Indonesia, and passed along to the U.S. Embassy.

The Khmer Rouge soldiers kept the merchant sailors on board but took the nonessential crew off the ship. The Khmer Rouge commander, Sa Mean, ordered the ship to the Cambodian port of Kompong Som. As the ship steamed through the Gulf of Thailand, American military aircraft—alerted by the SOS—harassed the Mayaguez by buzzing the ship, strafing the sea in front of its bow, and dropping tear gas on the deck. The harassment forced the Mayaguez to anchor off the coast of Koh Tang, a gulf island northeast of Poulo Wai.

The next morning, the Khmer Rouge loaded the Mayaguez’s crew onto a fishing boat and sailed for Kampong Som. As soon as the boats left Koh Tang, American fighters attacked, strafing the water and dropping bombs near the fishing boat. One of the Cambodian patrol boats was sunk. Another turned back to Koh Tang.

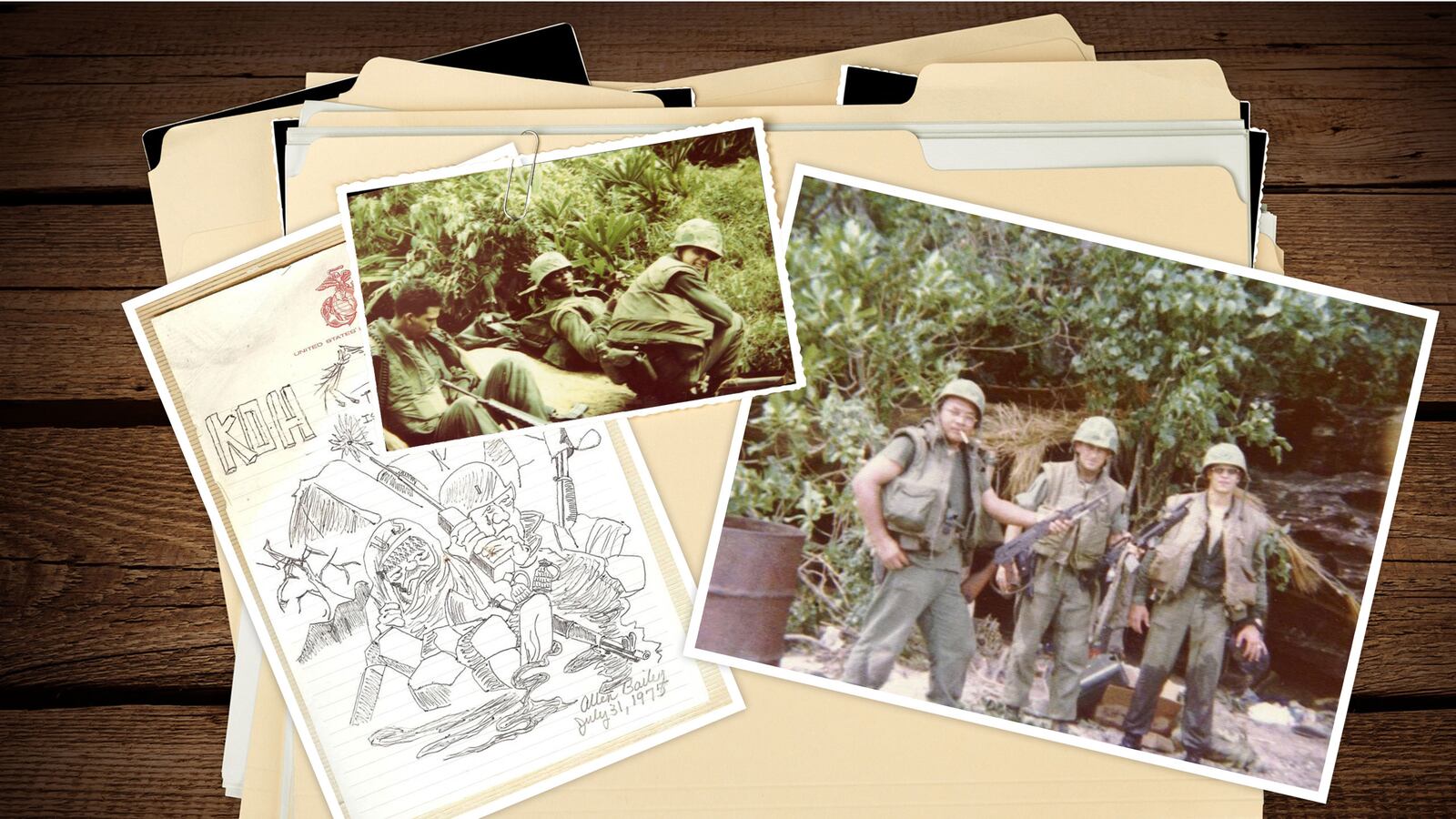

A drawing of Koh Tang.

Courtesy of Allen Bailey“One plane circled around while F111s bombed Kompong Som, Ream Port, the Kerosene Plant,” one of the Khmer Rouge soldiers said. “There was a constant flow of planes.”

The American pilots spotted the Mayaguez sailors on the deck of the fishing boat, and tracked it back to the mainland. Miller was taken to Rong Sang Lem, a nearby island, where he met with a Khmer Rouge commander. After a short interrogation, the commander asked Miller to call off the American bombers from the Mayaguez. Miller said he would call the company office in Bangkok using the ship’s radio, and that they would pass the message to the U.S. Navy. The commander agreed to let Miller and nine crew members start the ship’s engines and make the call the next morning.

While they waited, the Cambodians treated the crew well.

“Captain Miller and his men all say they were never abused by their captors,” press reports stated. “There were even accounts of kind treatment—of Cambodian soldiers feeding them first and eating what the Americans left, of the soldiers giving the seamen the mattresses off their beds.”

Back in Washington, the Ford administration struggled to come up with a response. In the wake of America’s humiliating departure from Southeast Asia, President Gerald Ford saw an opportunity.

“Rhetoric alone, I knew, would not persuade anyone that America would stand firm,” Ford said in his autobiography A Time to Heal. “They would have to see proof of our resolve. The opportunity to show that proof came without warning.”

Ford wanted a rescue mission, but the Navy’s 7th Fleet wasn’t prepared to answer the bell. The military was still catching its breath after the evacuations of Phnom Penh (Operation Eagle Pull, on April 12) and Saigon (Operation Frequent Wind, on April 29). Four Marines were killed in action during Operation Frequent Wind, and America’s appetite for more casualties had waned.

“President Ford and Secretary [Henry] Kissinger demanded from the military a speed of performance that it could not provide,” Admiral George Steele, commander of the U.S. Navy’s 7th Fleet, wrote in a letter about the Mayaguez incident later. “I think it was Alice in Wonderland at its worst.”

During a series of National Security Council meetings, Kissinger and Vice President Nelson Rockefeller pushed for the use of force to retrieve the hostages, advocating for a rescue mission to Koh Tang and punitive airstrikes on Cambodian infrastructure. They wanted to deter the Khmer Rouge and send a message to the communists that America wouldn’t back down.

Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger told Ford that Marines from the Philippines and Okinawa, using helicopters based in Thailand, could attack Koh Tang and liberate the ship’s crew. They could also retake the ship.

Schlesinger left out the fact that few of these Marines were combat veterans and many were at their first duty stations.

Ford ordered the Marines to take the island.

At the base on Okinawa, sheets of rain-soaked Staff Sgt. Fofomaitulagi Tulifua Tuitele as he trained alongside his men. A massive, 6-foot-2, 250-pound Samoan, with thick arms and a barrel chest, he was the platoon sergeant in charge of four squads of 12 Marines in the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines. The men called him “Sergeant T.”

Being a Marine had been Sergeant T’s life since he turned 18 years old in California. Born in Vailoa and raised in the village of Leone on the island of Tutuila American Samoa, he was just 10 years old when his father died unexpectedly. He moved in with his first cousin in Hawaii and shuttled between Hawaii and Samoa for years, before settling with his sister in California. When he turned 18, Tuitele joined the Marines because of a TV show and a stroke of luck.

Tuitele’s favorite TV show was Combat, a '60s series about American soldiers fighting the Nazis in France. He was drawn to the action and the camaraderie of the unit. He wanted to serve. While living with his sister in Los Angeles, he skipped school and went to visit military recruiters. His first stop was the Navy. They told him to come back in a few weeks. The Army and Air Force told him the same thing. His last stop was the Marine Corps. They told him to come back in two days to finish his paperwork.

“That’s why I’m a Marine,” Tuitele said.

Tuitele went to boot camp in 1966. The shock of getting screamed at by drill instructors as he stood on the yellow footprints that welcome every recruit—and the sight of his newly shaved, practically bald head—still reverberated as he lay in his bunk the first night. Overhead, he heard planes leaving San Diego. Alone in the dark, he missed home. All he wanted to do was fly back to Samoa.

“What the hell am I doing?” Tuitele asked himself.

Fofo Tuitele with captured AK-47, Koh Tang Island, May 15, 1975.

Fred Morris/Koh Tang Beach ClubThis wasn’t like the TV show. But over time, the discipline and hard training of the Marine Corps became his new normal. By the time he graduated, he was one of the top recruits.

The specter of Vietnam hung over the training. Tuitele said everyone knew they were likely headed overseas. After boot camp, but before advanced training, the 1st Marine Division had the recruits muster at their headquarters. One of the division’s senior sergeants stood in front of the formation.

“OK, I got some good news and bad news for you all,” he said. “First, how many shot ‘expert’ on the rifle range?”

Tuitele and five others raised their hands.

“OK, you guys step forward,” he said. “The rest step back. The bad news: all you guys back there are heading to Vietnam after training. You guys in front here are going to be assigned to sniper school—and then you’ll be coming back here, and then go to Vietnam.”

After three months of sniper training, Tuitele boarded the USS Johnson and sailed to Vietnam. He spent his first tour in 1967 as a sniper with the 5th Marine Scout Snipers, hunting Viet Cong in the jungle.

His second tour was with Lima Company 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines. The battalion—whose motto was “Consummate Professionals”—received two Presidential Unit Citations for extraordinary heroism during the war. Based in south Vietnam, the unit took part in operations in Chu Lai, the Que Son valley and fought in the Battle of Hue during the Tet offensive. The Battle of Hue was one of the bloodiest and longest battles of the war.

His request for a third tour was denied.

Instead, the Marines sent him to the barracks at Naval Station Sangley Point in the Philippines—then on to Pearl Harbor for three years. He got married in 1971 to his sweetheart Patricia and had three kids— Jason, Brian and Emmalia. After Hawaii, he was based at California’s Camp Pendleton, where he had first started his journey, before taking a platoon sergeant billet with the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines at Camp Schwab on Okinawa.

Camp Pendleton, April 4, 1975.

Courtesy Allen BaileyTuitele was a soft-spoken leader who looked after his men. He didn’t see race or class. Once, Al Bailey, a 19-year-old private from Maryland, said Tuitele broke up a fight between two Marines by knocking their heads together.

“Marines don’t fight Marines,” he barked at his men.

Once a Marine, always a Marine.

Tuitele was in the field training in May 1975 when word came down to pack up the gear and head back to Camp Schwab. Training was over. The Marines climbed into trucks and returned to their camp just before midnight. As the one convoy pulled in, Tuitele noticed another line of trucks parked near the barracks. They were told to put their gear in boxes and then board the waiting trucks. Rumor flew through the ranks as each man loaded his gear into a box. Something was going on, but no one knew what.

All they knew was this wasn’t part of training.

The trucks took the Marines to Okinawa’s Kadena Air Base, where Air Force C-141s were waiting to take them to Thailand. They packed into the gray cargo plane like sardines. Tuitele, still soaked by the rain, shivered all the way across the South China Sea.

After seven hours, the plane landed at Nakhon Phanom and the Marines filed off and got in formation. By then, RUMINT—rumor intelligence—was rampant. Tuitele heard stories about civilian seamen taken hostage by Cambodians, but he wasn’t sure how his unit fit into the plan to rescue them. He wouldn’t get a full brief for a couple of hours. First, the Marines were taken to an empty hangar with rows of cots, where they crashed.

After rest and chow, Tuitele and the other Marines got their first mission briefing. It was true: Americans had been taken by the Khmer Rouge. The Mayaguez sailors were being held on the Cambodian island of Koh Tang.

While Marines stationed in the Philippines retook the Mayaguez, Tuitele’s unit would attack Koh Tang just before sunrise—and rescue the crew.

Koh Tang island is made up of a wide north end in a vaguely humanoid shape, with stubby “legs” up top, and a thin strip of land that links to a smaller south side. The American crew was being held in a compound near the East Beach—on the northern side of the island’s “left leg”—according to intelligence reports.

The main assault of 600 Marines would attack two beaches. One group would hit East Beach in five CH-53 Knives and three HH-53 Jolly Greens. Two helicopters would attack the West Beach, opposite East Beach, less than a mile away through thick triple-canopy jungle, as a diversion. The West Beach Marines would link up with the main attack force on East Beach as they pushed into the island from the beach. A second wave would arrive soon after to get the whole 2nd Battalion to the island.

Resistance on Koh Tang was minimal, intelligence reports estimated. There were no more than 50 soldiers on the island.

But what the Marines didn’t know is that these estimates were incomplete and incorrect. Instead of a few dozen “Cambodian irregulars” and their families, some of the most experienced Khmer Rouge soldiers were on Koh Tang in heavily fortified bunkers and trenches. The Khmer Rouge soldiers were armed with anti-aircraft guns, machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades and mortars. A 75-mm recoilless rifle was positioned on West Beach.

As the first wave of 179 Marines headed for Koh Tang’s East and West beaches at sunrise on May 15, 1975, they had no idea what awaited them.

Thick black smoke billowed from below as the U.S. Air Force HH-53 Jolly Green helicopter raced toward Koh Tang’s sandy East Beach.

Tuitele saw the smoke from the helicopter’s window.

He tugged on the sleeve of a Marine near the window and pointed at the smoke, now growing darker and thicker as the helicopter approached the island.

“What’s that?” he mimed in sign language, the helicopter engines making it impossible to talk without a radio.

The Marine keyed his headset and got a report from the cockpit. Tuitele leaned close as the Marine yelled over the rotors.

“A helicopter was shot down on East Beach.”

Tuitele’s mind raced. All he wanted to do was get down there and help his men. He started to go over his battle drills. It was going to be a hot landing zone.

The helicopter jinxed and juked as it approached the East Beach. Just when Tuitele thought the helicopter’s wheels were going to touch the sand, the engines revved and the pilots took off again. They circled the island before landing on West Beach—less than a mile away from the downed helicopter and the Marines pinned down on the other beach.

Tuitele heard the pitch of the helicopter’s engines change as it started to descend, hovering just above the ground. If they didn’t jump now, the Marines were going back to Thailand.

“Go! GO!”

Tuitele dropped into a maelstrom of grit kicked up by the rotors. It took him a second to get his bearings before he started toward the jungle line. Mortar rounds exploded around him. He spotted a cluster of olive green men dug into the beach. They were taking cover from machine-gun fire coming from deep inside the triple-canopy jungle.

Tuitele wasn’t happy. This wasn’t how he’d trained them.

“Calm the hell down and listen,” Tuitele yelled over the roar of guns and helicopters. “Get off your head and let’s go. Spread out.”

The Marines looked at their platoon sergeant—all 250 pounds of muscle and fury—and weighed what scared them more: the Khmer Rouge machine gun or an angry Samoan.

The Samoan won.

That’s when they started moving, towards Koh Tang’s deep jungles, towards the bullets thundering by them—and, they hoped, towards their fellow soldiers and the Mayaguez’s captured crew.

We know you’re hooked. Read the next installment... in which the Marines learn a horrible secret about their mission to Koh Tang.