Quite apart from its many other virtues Kenneth Weisbrode’s wonderfully readable Churchill and the King will go far to correct the mistaken impression that the British sovereign is merely a figurehead, trotted out in full court dress and crown for the opening of Parliament and other symbolic ceremonies. Prime ministers come and go, but so long as he or she lives the sovereign remains, receiving and reading all state papers, and meeting once a week with the prime minister to advise, enquire, and comment—sometimes sharply, as was the case with Queen Elizabeth II and Mrs. Thatcher—on affairs of state. The sovereign is not a rubber stamp or a piece of decorative blotting paper, whatever may be the case in Sweden or the Netherlands. For over five hundred years English kings ruled by divine right and brute force, brooking little interference from Parliament, but after the great political struggle of the 17th Century, culminating in the trial and execution by Parliament of Charles I for treason, successive kings and queens carved out over time a carefully designed and infinitely malleable role for themselves as “a constitutional monarch,” whose powers are neither explicitly defined nor easily visible. The United Kingdom has no Constitution like that of the United States, the guarantee that the customs, freedoms and rights of British subjects will be respected does not lie in a written document, but in the person of the sovereign—and also, it must be said, in his or her commonsense, judgment, experience, and deep understanding of just what the British people will or will not accept. Occasionally, British monarchs have got this wrong—James II underestimated the country’s distrust of a Catholic sovereign under the influence of France, George III failed to understand the depth of his American subjects’ dislike of taxation without representation, Edward VIII was mistaken in supposing that his people would accept his marrying a twice-divorced American socialite—but in general British sovereigns have usually had a better understanding of just what the British people would, or would not, put up with than many of their prime ministers.

The monarchy is, and is meant to be, a mystery, but behind the jewels, the parades, the glamor and the gossip value of the royal family there lies a fundamental fact of British life: all politics and all public institutions revolve around the fixed pole of the monarch, he or she is the cornerstone of the arch that supports the state, and holds together what would be an otherwise disruptive and unstable union of England, Wales, Scotland, and northern Ireland; he or she is bedrock, in the absence of which we would need to totally reinvent our country from top to bottom from time to time, as the French have done through revolutions, empires, and successive republics, a messy and uncertain business compared to the stability of the British monarchy.

Perhaps no British prime minister has understood this better than Winston Churchill, who served as a minister of state under Edward VII and George V, and as prime minister under George VI and Elizabeth II, and whose father and grandfather served in high offices under Victoria.

The relationship between Churchill and King George VI is a great story, and Weisbrode tells it well, and does a wonderful job of showing how the childhoods of the future King George VI and Winston Churchill had strong similarities—a glamorous, distant mother, a remote and ill-tempered father, a beloved nanny, a spotty education, and a dramatic baptism of fire in the First World War—that made their relationship so smooth in World War Two. Those who have seen and enjoyed The King’s Speech may have been slightly misled by Colin Firth’s tall and physically robust portrayal of His Majesty, whose problems were not limited to a stammer—he was short, very slight, shy, knock-kneed so badly that his father had his legs placed in painful braces, embarrassed by prominent ears, and suffered since early childhood from explosions of temper, tantrums as they were called, as well as from living in the shadow of the smooth self-confidence, social ease and immense popularity of his older brother the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII and Duke of Windsor), and also experienced a long list of ailments exacerbated, no doubt, by the family habit of chain smoking (he, his father, and his grandfather all died of lung ailments).

Called to the throne by his brother’s abdication in 1937, “Bertie,” as the King was known in the family, was fortunate in having a strong, shrewd, and determined wife (the future “Queen Mum”) and two photogenic daughters, Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret Rose. Churchill would not have been the King’s choice for prime minister on May 10, 1940, when Neville Chamberlain was obliged to offer his resignation after “the Norway debate,” in which it became apparent that while he still had the loyalty of most of the Conservative Party, he no longer enjoyed the confidence of the House in his handling of the war. A proud, tough, and ruthless politician in dealing with everyone but Hitler, he had been greeted by cries of “Resign! Resign!” from both sides of the House, his face a display of fury, an outburst that convinced him that he would have to go.

Both the King and the Queen were firm supporters of Chamberlain, and hoped that if he did have to go, he would recommend that the King send for Lord Halifax, known as “the Holy Fox” to insiders, the Foreign Secretary whose record on appeasement of the dictators was in tune with that of Chamberlain, and whose calm, aloof, aristocratic persona—he was also an English country gentleman to the core, nor did it hurt that like the King he suffered from a speech impediment—they liked so much that they gave him a key to the Buckingham Palace gardens, so he could walk through them on his way to the Foreign Office.

Churchill, on the contrary, they regarded with alarm, a loose cannon, a rogue elephant. He had, as Weisbrode points out, a great reverence for the institution of monarchy, but a spotty record with monarchs. Invited to dinner at Buckingham Palace the young Churchill had committed the ultimate social sin of arriving late (royalty must never be kept waiting), and King Edward VII commented that the young Churchill was “almost more of a cad in office than he was in opposition,” a view shared by his son George V, who was heard to snort with indignation at Churchill’s reckless opinions and occasional eccentricities of dress. In the film The King’s Speech the Duke of York (the future George VI) is portrayed as having a certain tolerance for eccentricity, but in fact all the Windsors (a tactful World War One wartime change of the family name from the more German sounding Saxe-Coburg-Gothas), from Queen Victoria to Queen Elizabeth II, have all shared an eagle’s eye for a misplaced decoration, an unbuttoned button or the wrong shade of gloves, and George VI was no exception.

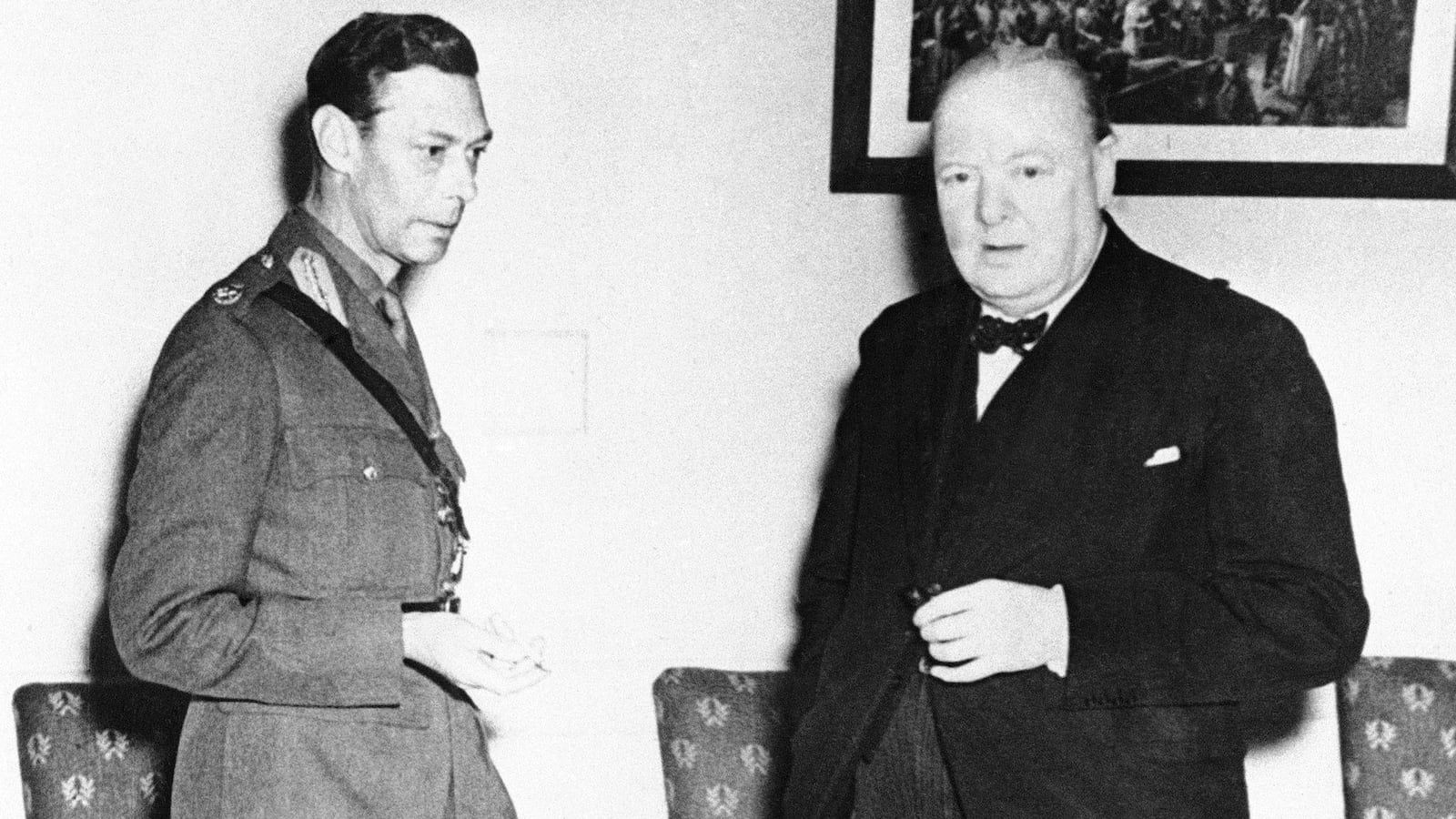

As for Churchill, he enjoyed throughout his life the happy illusion that he had charmed or won over to his point of view everybody he talked to, irrespective of rank, and would not therefore have noticed any hesitation or reserve on the part of Their Majesties when he arrived at Buckingham Palace to kiss hands and accept the prime ministership. They, on their part, could hardly have forgotten that Churchill had given reckless and poor advice to Edward VIII over “the King’s matter,” and even spoken in favor of his marrying Wallis Simpson, a subject about which the King, and even more firmly the Queen, were and remained quietly unforgiving. Very fortunately, the perfect manners of the King and Queen and Churchill’s indomitable self-regard combined to smooth what otherwise might have been an embarrassing moment, and to produce a partnership that was at the heart of Britain’s war effort and brought out the best qualities in both men. It is often said that Churchill was wrong about most things, but right about the one thing that mattered, which was that Hitler and the Nazi regime were evil, and there is some truth to this.

Weisbrode brings out the great value to Churchill of having to explain in an orderly manner once a week exactly and frankly what he knew, what was happening, and what was planned to somebody with whom he could not be dismissive or impatient or lose his temper. Mrs. Churchill, at the height of the war when Britain stood alone, wrote to him to complain about his treatment of his staff, not to speak of the Cabinet and the chiefs of the Imperial General Staff, and pointed out he could sack anybody he wanted to in Britain except the King and the Archbishop of Canterbury, but in fact the one person (apart from Mrs. Churchill herself) whom he could not bully or lose his temper with was the King. At first he gave offence by arriving late for his meetings with the King, but this was solved by the happy expedient of making the weekly visit a luncheon—Churchill’s “tummy” rather than his watch (which he was apt to disregard) told him when it was time for a meal—and interestingly enough, when the King was absent, the Queen substituted for him, although Churchill was not usually good about sharing political and military information with women. But the Queen was a different matter, and he unflinchingly passed on his news about matters of state to her, knowing that she and the King shared everything—to tell her something was to tell him—and perhaps recognizing that there was “a drop of arsenic in the center of that marshmallow,” and that she could more than hold her own against him if she had to. Weisbrode points pout correctly that the King’s contact with the people was closer than Churchill’s—His Majesty traveled around the country and made it a point to visit cities that had been bombed, they were, after all, his people, and whereas Churchill was apt to be blinkered by class prejudice (he was the grandson of a Duke) or sentimentality towards what were then called “the lower classes,” the King was not: each of them, from Duke down to dustman was his subject, following the ancient tradition that everybody outside the royal family is a “commoner,” whatever their title.

Although many people imagine that Churchill was sometimes impetuous and that it was the King’s job to urge caution on him, this does not seem to have been the case. After his initial sympathy for appeasement the King became just as determined to defeat the Germans and get rid of Hitler as Churchill had been, it was the King’s job to listen, to study the documents and master the facts, to comment and advise, and of course to ask the all-important questions that only the monarch is entitled to ask. The growing respect, and even friendship between the two men is a delicate and touching story and Weisbrode tells it wonderfully, showing how often (and how tactfully) the King reached out to save Churchill from his worst instincts.

Weisbrode does a very good job of illuminating the bonds that drew two men with such different personalities together, perhaps the strongest of which was that both men were physically courageous. Despite his unassuming appearance, the King as a young midshipman had served bravely in action at the Battle of Jutland, the biggest naval battle of World War One, on board HMS Collingwood, sticking his head out of his turret to observe the enemy’s shots straddling the ship until an officer shouted at the prince to “Come down before you get your head blown off!” This was a formative moment of his life, like that of Churchill, who when he first came under fire, exclaimed how exciting it was “to be shot at without result.” They were perfect examples of le flegme anglais, a stolid indifference to danger best epitomized by Field Marshal Sir John French, commander of the British Army in France in 1914, who when he wanted to see what was going on simply stuck his head above the parapet of a trench, wearing his scarlet banded and gold braided field marshal’s cap, without giving a thought to enemy snipers. When 10 Downing Street was bombed Churchill opened the door of the shelter to get a better look at the raid, despite the protests of his staff. “My time will come when it comes,” he said, and from deep in the shelter a brave voice called out, “You’re probably right, sir, but there’s no need to take half a dozen of us with you.” When the King glanced out the window and saw a German bomber flying straight down the Mall towards him at rooftop height to bomb Buckingham Palace he was more interested in the spectacle than startled by it, even though the bombs exploded only a few yards away, shattering glass and shaking the Queen, who was in her bathroom fiddling with her eyelashes. (This incident was attributed to deliberate Nazi policy, but in fact took place because the German bomber pilot had bet his squadron mates that he could do it.)

Weisbrode’s book is full of these wonderful anecdotes, stories, and one-liners, many of which I have not read before, as rich as a plum pudding (a favorite of Churchill’s, who once said to his hostess, “It isn’t a dinner without pudding,”) a marvelous “read” for anyone who is interested in history, the Second World War or the British character.

What is more he has grabbed the bull by the right end, and dug a lot deeper into Churchill’s character than have many authors done in books much longer than his, and shown us a remarkable picture of life at the top in World War Two. Too little credit is given to the King for our victory in World War Two, but Weisbrode has taken a big step to put this right at last, in a book that describes with deft sympathy the relationship between two men who had, when it mattered, “bags of swank,” to use the old British army term for courage and swagger, and in the process of leading the nation, not only brought us to victory, but changed each other for the better.

This is popular history at its best. I wish I had written it, but am glad that I read it. It is a model of what can be done in a relatively short book, and more readable than many, if not most novels, despite its wealth of detail, and firm grounding in fact.