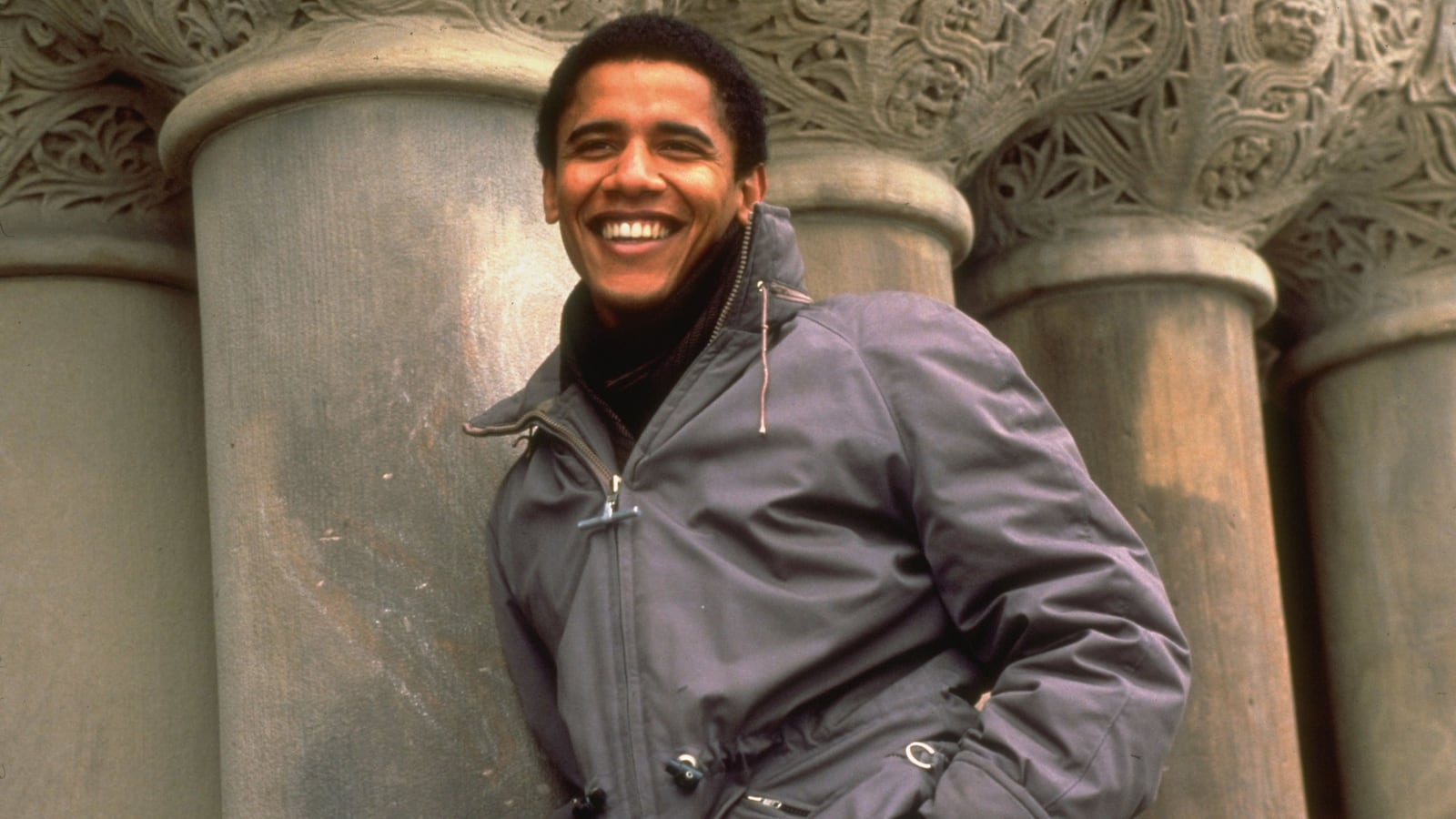

The Daily Mail’s sidebar of shame yielded a gem of a story on Thursday morning: “Barack’s passionate love letters to college girlfriend,” the headline teased. “Obama wrote of making love and ‘breaking sweat’ to girl who eventually wed Serbian boxer.”

So began the Mail’s breathless coverage of Barack Obama’s epistolary romance in the 1980s with his then-girlfriend, Alexandra McNear.

Some of young Barack’s love letters are purple and slightly cringey: “I trust you know that I miss you, that my concern for you is as wide as the air, my confidence in you as deep as the sea, my love rich and plentiful,” he wrote to “Alex” in September 1982.

Another from November is more flirtatious: He alludes to the challenges of a long-distance relationship, “which requires breaking some sweat. Like a good basketball game. Or a fine dance. Or making love... We will talk long and deep,” he promises, “and see what we can make of this.”

The Mail and every other mainstream media outlet pounced on the news Thursday morning that Emory University had acquired all nine of these letters–handwritten on lined yellow paper, paper torn from a spiral notebook, a notecard—for the school’s permanent library.

They’re about as juicy as one would expect from a sensitive, soul-searching young Obama–which is to say: not juicy at all.

But they’re nonetheless fascinating to read. Beyond giving us insight into the collegiate mind of our 44th president, Obama’s letters are a tribute to the art of letter writing.

It’s not just the visual and tactile components that make it an art form, but what the handwriting tells us about the processes of the writer’s mind.

For instance, a letter showing phrases tweaked and words faintly crossed out in favor of other words might make you wonder why the writer chose one word or phrase over another.

The handwritten letter exposes a certain vulnerability that we can’t see in digital letter writing. When composing an email, a word or phrase might be written and rewritten over and over again—and the reader will never know what had been erased.

This writer, for instance, obsessively tweaks words and phrases to the extent that an hour might be wasted on a single sentence. But my writerly self-consciousness doesn’t necessarily come across in a digital missive, because I can make words disappear. A misused word in a handwritten letter, by comparison, will be scribbled over so heavily that the reader can’t possibly see what nonsense was there before. Those ink splotches say a lot about how I write.

We’ve always enjoyed reading handwritten letters by great figures like Jane Austen and Winston Churchill because of the insight they give us into their lives: the crossed-out and underlined words, the after-thought annotations, the fervor in the writing that comes across not only in the language but in how the pen looks on the page.

There’s no doubt that letter writing is a lost art, mostly reserved for the occasional handwritten thank-you note or condolences for grieving loved ones.

This isn’t to discount the marvels of email, which instantly connects people all over the world and is conducive to our fast-paced lives.

But the differences between digital letters and handwritten ones fall in line with a broader cultural shift away from reading print to reading on screens. For many people, print vs. digital reading is still a matter of personal preference. But most of us have grown accustomed to consuming information instantly in digital formats.

The art of letter writing is harder to preserve than printed content because it’s so time-consuming. It can also feel precious and pretentious these days, associated with those people who spend an absurd amount of money and time on their elegant stationary and quill pen collections. (Who has that kind of money and time these days?)

Letter writing has always required a waiting period—the anticipation of its arrival in your mailbox, or the fear of what may happen by the time it reaches its destination. Minds may be made up, life-altering opportunities discovered, long-distance lovers distracted by new romances.

In films and novels, we’ve seen these letter writing narratives drive plots forward or determine characters’ fates, and the letter’s discovery is proof of life, death, love, or intent.

An obvious example might be Nicholas Sparks’ The Notebook: young lovers separated because of their different backgrounds grow further apart over the years because Allie’s mother intercepts Noah’s love letters and sabotages their romance. The plot shifts after the climactic canooing-in-the-rain scene, when Allie learns that Noah “wrote her 365 letters. I wrote you every day for a year.”

Letters also play important roles in Wes Anderson’s charmingly nostalgic films. Moonrise Kingdom’s young Sam and Suzy exchange love letters—written in childlike print and script on personalized stationary—as they plan to run away together. Sam also leaves a hilariously dramatic resignation letter for his fellow Boy Scouts when he escapes camp, as if the news is too painful to reveal in person.

Similarly, the adolescent playwright protagonist in Anderson’s Rushmore sends letters to express feelings he can’t convey verbally, whether arguing that Latin should continue to be taught at his school or professing his love to a teacher.

Letters are vital in fiction and non-fiction. Think of the sometimes unbearably moving letters home from those serving in wars to their loved ones at home. Think of the quotidian, but still cherished letters, from family members and loved ones separated by distance.

Hamlet’s love letter to Ophelia pleads that while she may doubt much else, “But never doubt I love.” What would Beaches be without CeCe and Hillary’s letters chronicling their triumphs, heartaches, and their feelings toward one another for good and ill? In Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City Michael Tolliver’s “Letter To Mama” coming out remains a classic.

Obama’s letters to an old flame recall other love letters by prominent and impactful public figures: literary lions, philosophers presidents, actors, tyrannical rulers, and so on.

Shortly after his marriage to Joséphine de Beauharnais, a besotted and possessive Napoleon sent a series of passionate, steamy love letters while commanding the French army near Italy.

In April 1796: “I have your letters of the 16th and 21st. There are many days when you don’t write. What do you do, then? No, my darling, I am not jealous, but sometimes worried... But you are coming, aren’t you? You are going to be here beside me, in my arms, on my breast, on my mouth? Take wing and come, come! A kiss on your heart, and one much lower down, much lower!”

Napoleon was such an obsessive letter writer that he appeared to have written multiple missives on the same day describing how they will make love when she visits.

“I am going to bed with my heart full of your adorable image. ... I cannot wait to give you proofs of my ardent love,” he wrote in November 1976. And again: “How happy I would be if I could assist you at your undressing, the little firm white breast, the adorable face, the hair tied up in a scarf a la creole. You know that I will never forget the little visits, you know, the little black forest. ... I kiss it a thousand times and wait impatiently for the moment I will be in it. To live within Josephine is to live in the Elysian fields. Kisses on your mouth, your eyes, your breast, everywhere, everywhere.”

Nabokov’s earliest letters to his wife Véra reveal a man intoxicated by love and a magician with words.

“I want to tell you that every minute of my day is like a coin with you on the other side, and that if I hadn’t remembered you every minute, my very features would have changed,” he writes in 1926.

Equally fun to read are his lyrical observations of the mundane. The Metro in Paris “stinks like between the toes and it’s just as cramped.” When trying to quit smoking, conjures an image for Véra of angels lighting up cigarettes like naughty middle-schoolers, then flicking them away when the Archangel floats by (“This is what falling stars are.”)

Kafka’s letters to his first wife, Felice Bauer, reflect some of the defining qualities of his fiction, like the sense of striving through bleakness, miserably hopeless but nonetheless determined. In 1913, he wrote passionately to his then-fiance: “I belong to you; there is really no other way of expressing it, and that is not strong enough.”

His letters reveal a man who is often insecure, writing that his “energies have always been weak” and confessing his jealousy of “all the people in your letter, those named and those unnamed, men and girls, business people and writers.” He turns out to be the type who desperately wants what he can’t have until he has it, in which point he retreats into himself.

“The life that awaits you is not that of the happy couples you see strolling along before you in Westerland,” he writes when Baueur finally responds to his entreaties to marry her, “no lighthearted chatter arm in arm, but a monastic life at the side of a man who is peevish, miserable, silent, discontented, and sickly; a man who, and this will seem to you akin to madness, is chained to invisible literature by invisible chains and screams when approached because, so he claims, someone is touching those chains.”

Winston Churchill was also a prolific love letter scribe. “Marry me—and I will conquer the world and lay it at your feet,” he wrote in 1899 to Pamela Plowden, his first love. (The letter sold for $113,782 at a Christie’s auction this year.) The British prime minister also wrote to his wife Clementine whenever he left home.

Now we can add Barack Obama’s letters to this canon of letters, a tribute to the dying art. Or, as Virginia Woolf put it, “the humane art, which owes its origins to the love of friends.”