This is the latest installment in our monthly series, The World's Most Beautiful Libraries.

On my first visit to Biblioteca Pública Arús, I managed to walk past it—twice. Granted, I may have been distracted by the enticing smell of the newly fried tapas from the bar next door, or the tanned, toned Mediterranean types effortlessly rollerblading past outside, but, as I made my way up the elegant staircase leading up to this secret library, I felt a pang of guilt for having overlooked it for so long.

Hidden on the second floor of one of Barcelona’s characteristic late 19th-century townhouses, Biblioteca Pública Arús (or the Arús Public Library) was inaugurated on April 24, 1895, as one of the first dedicated public libraries in the Catalan capital. It was donated to the people of Barcelona by local playwright, journalist, philanthropist and Freemason Rossend Arús to promote the education of the working classes. Even though Arús himself died in 1891, he left clear instructions in his will for how he wanted his fortune—and his home—to be put to good use.

Situated in Rossend Arús’ former residence at Passeig de Sant Joan, 26, the Arús Public Library houses some 80,000 volumes of books, booklets, manuscripts, documents, microforms and electronic resources. In addition to one of the largest reference works on Freemasonry in Spain, it also boasts one of the world’s most comprehensive Sherlock Holmes collections.

Aside from its scholarly riches, the Arús Public Library also offers a fascinating insight into Catalonia’s modernist architecture. Constructed in 1875 by Pere Bassegoda i Mateu, the building is typical of the Eixample neighborhood in which it sits. “Eixample” is translated as “extension” and refers to the urbanization project that saw the city of Barcelona expand beyond the suffocating confines of its medieval walls in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The brainchild of Ildefons Cerdà, the Eixample neighborhood is characterized by its strict grid pattern, comprised of octagonal blocks designed to facilitate the flow of traffic, and distinctive modernist houses with their mind-bendingly colorful facades.

However, there is nothing much to catch the eye about the greyish-beige exterior of Passeig de Sant Joan, 26, which pales in comparison with many of its more ostentatious neighbors. In fact, were it not for the ornate modernist lantern casually hanging over the main entrance, bearing the words “Biblioteca Pública Arús”, you’d be forgiven for walking by without giving it a second thought.

Those who step across the threshold are immediately transported into a realm far removed from the hustle and bustle of the chaotic city outside. A cool, elegant marble staircase guarded by a small-scale replica of the Statue of Liberty leads up to the entrance of the library. Designed by Catalan sculptor Manuel Fuxà, The Catalan Liberty is inscribed with the words “Anima libertas”, or freedom of the soul—reflecting Arús’ belief in the intellectual liberation of the working classes through education—while the tiles at her feet spell out “Salve”, or Latin for “welcome”.

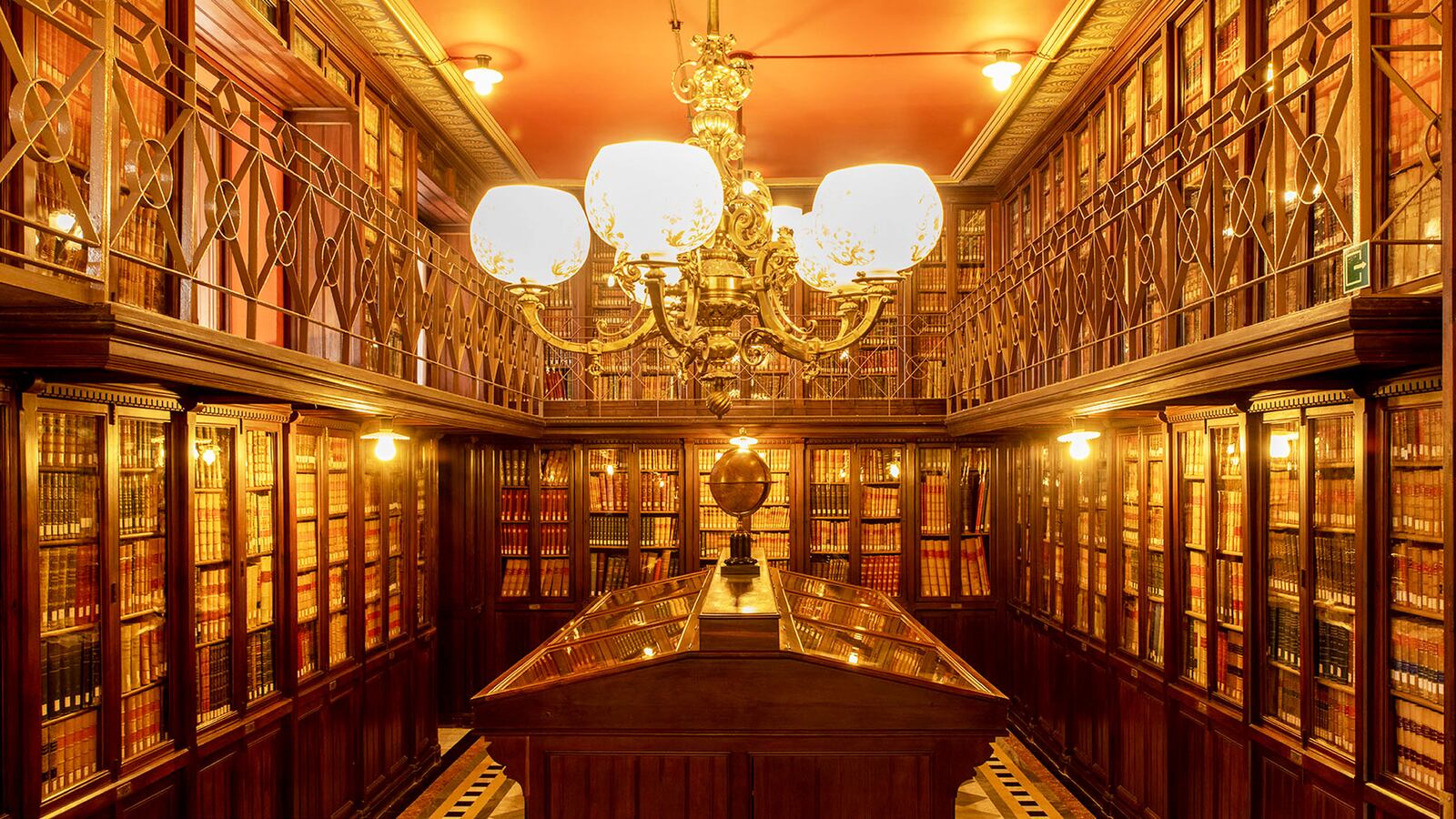

Once inside the library, you will first discover the exhibition room, with its floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and, further in, the reading room, with its magnificent wooden lamppost, complete with intricate bronze arms, holding six translucent glass lights, its arched ceiling and wall panels bearing the names of prominent cultural figures from Catalonia. Make sure not to miss the delightful music room, with its geometrically designed marble floor and ceiling lights adorned with delicate floral reliefs.

Freemasonry has been a central theme throughout the Arús Public Library’s checkered history. Unlike the Anglo-American tradition, which typically requires candidates to express a belief in deity, the Continental European variety of Freemasonry, generally found in Catholic countries, has often been viewed as an outlet for anti-Catholic disaffection. This took on a whole new meaning for the library in the late 1930s, when the end of the Spanish Civil War saw Barcelona and Catalonia fall under the control of Fascist dictator Francisco Franco.

The occupation of Barcelona by Franco’s army in 1939 marked the start of a period lasting almost four decades, during which Spain languished under a brutal Fascist regime. During his reign, Franco’s relentless persecution of his political opponents had an especially harrowing impact on Catalonia and the Basque Country. Backed by the Church, he made Catholicism the only accepted religion, and prohibited the use of the Catalan and Basque languages and cultural expressions outside the home, including the use of traditional Catalan and Basque names for newborns.

A close ally of Adolf Hitler in Germany and Benito Mussolini in Italy, Franco’s sworn enemies included the labor unions, Communists, Jews, homosexuals, and any groups promoting liberal or anti-clerical values, such as the Freemasons. Franco passed specific legislation to outlaw Freemasonry, and thousands of trials were held, resulting in firing squads, extensive prison sentences, property seizures, and exile, for those found guilty of Freemasonry. Following the death of Franco in 1975, it took a further four years for Spanish Freemasons to be legalized and have their rights restored.

Maribel Giner, Director of Biblioteca Pública Arús, explains that the Masonic links of the library placed it in a precarious situation after the Spanish Civil War. In 1939, the library closed to the public to keep it safe. It did not reopen again until 1967.

“At the end of the war, the library had a reputation for being ‘Red and Masonic’,” Giner explains. “Red—or Communist—due to its backing of the labor movement and commitment to educating the working classes, and Masonic, because of the collection it inherited from the private library of its founder.”

The closure of the library prevented it from being plundered and, while books were destroyed or requisitioned elsewhere, the Arús Public Library’s collection was kept intact. The concierge, who lived with his family in part of the property, was charged with not letting anyone in without express permission from Barcelona City Council.

But the history of the library does not end there. In 2011, it received a collection on Sherlock Holmes, donated by Catalan collector Joan Proubasta, consisting of more than 6,000 books in 42 languages, and more than 2,000 related objects, from comics to posters, stamps, statues, puppets and insignia. It is one of the most extensive collections in Europe and the largest in Spain. Why did Proubasta make this donation to the Arús Public Library? It turns out that Holmes’ creator, Arthur Conan Doyle, was a Freemason.

For any library enthusiasts staying in Barcelona, Maribel Giner believes the Arús Public Library is worth a visit.

“This is a well-preserved 19th-century library that has maintained its original design details. Stepping in here is like being transported to another era, and also an opportunity to explore a piece of Barcelona's history,” she says.