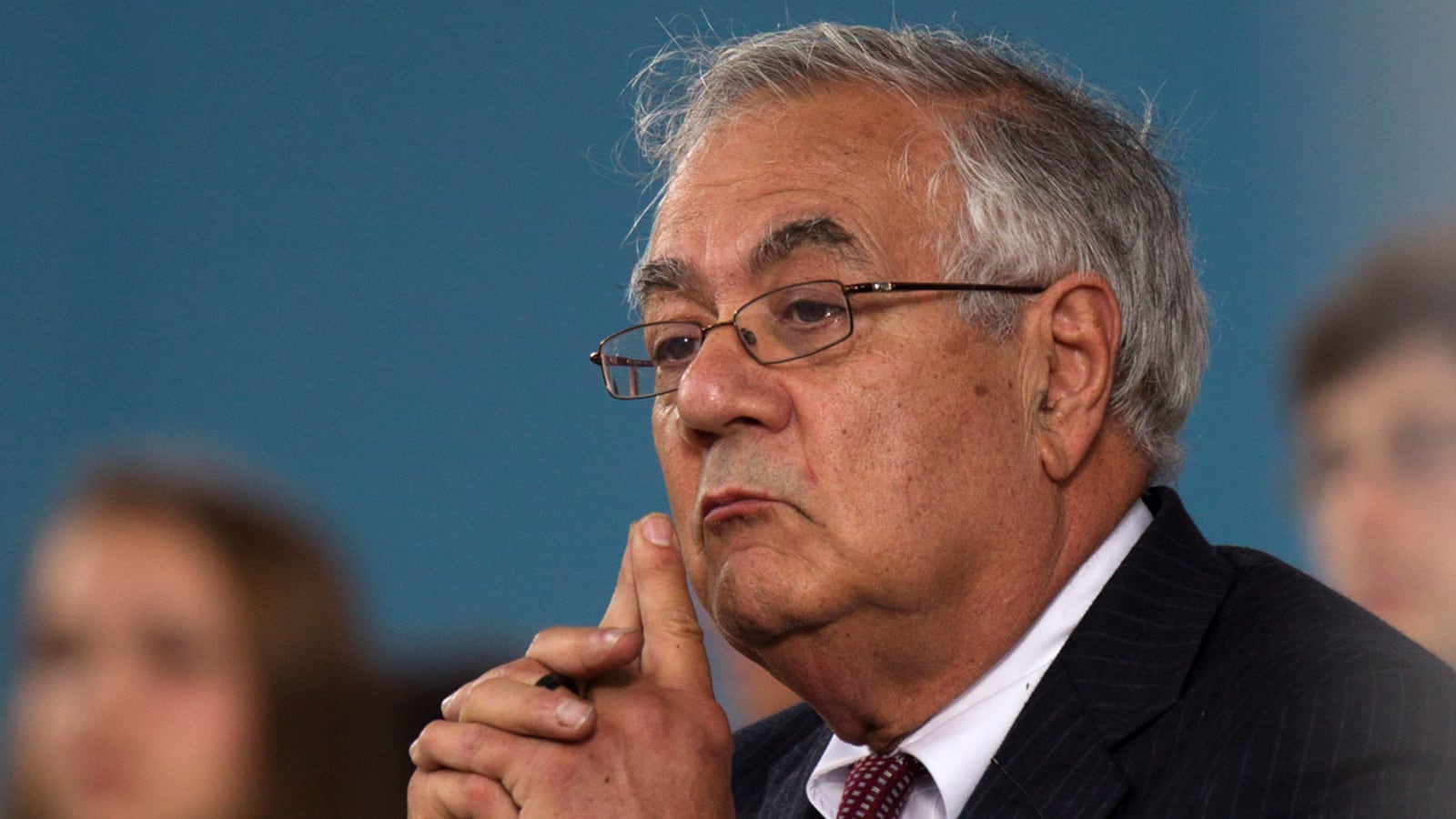

It’s been two years since President Obama signed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act into law, but the new banking regulations are still a topic of huge debate. Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney has vowed to repeal Dodd-Frank if elected, a position that has come under increased scrutiny since JPMorgan Chase revealed losses that could run as high as $7 billion from a failed bet in derivatives trading. Eleanor Clift chatted with one of the law’s sponsors, Rep. Barney Frank (D-MA), about the motivation behind the law and why the Morgan situation is renewing calls for market reforms.

Clift: I attended an event at the MPAA the other night, and (former Senator) Chris Dodd said he heard his name invoked so many times with Dodd-Frank, he thinks he should get residuals. Dodd-Frank, your legislation, is the centerpiece of the debate right now. What are the implications of that?

Frank: It certainly helps reaffirm our argument—on several fronts. First of all, I will take credit along with Chris and the people who work with us—if this [JPMorgan] event had happened five years ago, I think there would have been a lot more panic and nervousness in the economy. The fact is that people understand banks today are better capitalized. This would have caused a tremor a while ago—and it did not. There was no sense that stability was at risk, probably because of what we’ve done. Secondly, it vindicates our views on derivatives.

People have been talking about the Volcker Rule and the banks, and that’s an important piece of it. But they shouldn’t forget the other piece, which is no matter who is doing derivatives, whether in a bank or on the outside, there are these safeguards. Whoever is doing these things has to have enough money to pay up if the bets go bad.

AIG was a non-bank doing derivatives, so simply getting out of a bank is only part of the issue. It reaffirms that derivatives are inherently risky, and even the best-run banks—and JPMorgan is one of them—cannot avoid the risk. Our job is not to stop these people from losing money. Our job is to stop their money losses from spilling over into the rest of the economy and other people.

Republicans have a bill that they put through our committee—that they were going to try to put through the House Agriculture Committee, too; we were fighting it—that said that if an American institution conducts derivative trades through a foreign subsidiary that it’s not under any American regulation. That bill is pending right now, although I think they probably aren’t going to bring it up.

Clift: I hear two lines of attack from Republicans: one that Dodd-Frank hasn’t solved the problem, and two, that JPMorgan lost $2 billion, they absorbed it, so what’s the big deal? Why do we need more regulation?

Frank: They’re contradictory.

Clift: I know they’re contradictory.

Frank: It was never intended to solve a problem of a financial institution losing money—that’s not the problem. It’s beginning to have an effect on the contagion. The Economist, in an hysterical attack on the financial-reform bill, cited as one of its worst impacts that JPMorgan Chase would have to spend between $400 million and $600 million the first year to comply with the rules. If $2 billion ain’t nothing, what’s $400 or $600 million? It’s eight times as much as they’ve given the Commodities Futures Trading Commission.

The rules aren’t ready yet—they’re slowing the rules down. They’re lobbying hard. First of all, they have underfunded the two entities that do derivatives—the CFTC and the SEC. They haven’t given them enough money. Second, they put in a lot of comments that the agencies have to monitor and then they take them to court, say they didn’t do the cost/benefit analysis. The CFTC put a limit on how much you can buy oil, if you never use oil, position limits. They took them to court over this. They took the SEC to court over the rights of a board of directors—that’s what takes a while. The CFTC is a five-member commission, and until recently the third Democrat was not a good guy from our policy standpoint. So they slow it down by underfunding the two agencies that deal with derivatives by flooding them with comments that, by law, they have to analyze and then suing them .

Clift: If this had happened to a less well-capitalized bank, what would the impact be?

Frank: If the bank was at the margins in its capital, it could have caused real problems. If it was a less well-capitalized bank and they fell below a critical level, they would have had to raise new capital. They could have had trouble raising new capital, it could have been problematical.

Clift: Would taxpayers be hurt?

Frank: Not unless they were unable to meet the payoff of their deposits.

Clift: That doesn’t sound like it would be so bad if it happened to a less well-capitalized bank?

Frank: It would depend if the whole bank went under.

Clift: If you’re just a voter out there, you wonder if this is an aberration, or is it more widespread?

Frank: No bank would have been considered better-run than JPMorgan Chase, so if it happens to them, that’s the point. This is not about a lousy institution doing stupid things—this is inherent in the nature of what they were doing with these kind of hedges. What’s important is not simply the Volcker Rule, but a whole new set of rules that are about to be adopted that say that if you do these trades, you have to have margin, they have to be made public. If we had these rules, everybody would have known what was going on at JPMorgan Chase long before the anvil dropped on their head.

Clift: Romney is saying he would repeal Dodd-Frank—and it’s a mantra on the campaign trail along with “Obamacare.”

Frank: I think that undercuts him substantially. When they talk about repealing the financial-reform bill—they’ve moved to repeal, they know it’s more popular. The problem is the Republican presidential candidates said that—because they were competing for all the crazy people in the Republican primaries. The Republican Congress has not moved to repeal it. They’ve moved to make some small changes—they’ve moved to repeal the health-care law, but not Dodd-Frank.

Clift: The Volcker Rule is supposed to go into effect this summer.

Frank: In a couple of months, and there’s no undoing that. The tougher version of it will take effect. The Volcker Rule says banks shouldn’t be doing this—but we then need the other rules that regulate how other people do it: they have to make the price public, they have to go on exchanges, and they have to have enough margin to pay off if they lose.

Clift: Does this undercut the Republican theme of less regulation?

Frank: No question. One very specific bill they were pushing which would exempt JPMorgan’s activity by saying if an American institution does derivatives through a foreign subsidiary, it’s not regulated. It went through the committee that I’m on. We objected. Then it had to be voted on in the Agriculture Committee as well—two committees have jurisdiction over these futures. And with the Agriculture Committee, the Republicans just pulled the bill from the agenda.

Clift: Some people say we should just reimpose the Glass-Steagall Act. It seems like a neat, easy solution.

Frank: The Volcker Rule is Glass-Steagall updated. There was no such thing as derivatives under Glass-Steagall. So if all you did was reimpose Glass-Steagall, then derivative transactions outside a bank wouldn’t be regulated.

Another thing Glass-Steagall wouldn’t do—a big part of this problem was the subprime loans. Glass-Steagall didn’t do anything about subprime loans. A bank could make them, and even worse, they didn’t do anything about securitization—you make a bunch of loans, then package them up and sell them. Glass-Steagall is 80 years old—it didn’t know from these.

Clift: There’s a huge partisan divide in Congress. Can you outline what it is briefly?

Frank: It’s the extremist Republicans. Ben Bernanke, Sheila Bair, and Hank Paulson—three Bush appointees are essentially supportive of the things we’re talking about here. If you go by the Treasury, you’ll see the portrait outside Geithner’s office of Paulson, and he takes credit for a lot of the Dodd-Frank stuff. Generally, he pushed a lot of it. But you have extremists today who really believe the free market should stand alone, and some of them say even if that causes a problem, that’s where you’re supposed to be. The Democrats’ position is the private sector should create the wealth, but you need rules to govern its behavior. The Republicans say no, leave them alone, they’ll do better without it.

Clift: What do you make of the chatter about how Obama has insulted Wall Street, and their feelings are hurt?

Frank: That’s absolutely right and that’s why they’re so agitated. That’s exactly right—and I don’t think it speaks well of them. I think that’s what motivated them. I am convinced more and more that people want psychic income from us—they want to be told how nice and good they are. I do not think that the harm we have done to them is real—the Republicans are the ones saying don’t let the Federal Reserve help the European Central Bank or the IMF. The Republicans are advocating policies they think are wrong, but we hurt their feelings, there’s no question about it.

Clift: President Obama’s remarks about JP Morgan were quite temperate, and yours have been, too, saying they’re a good bank.

Frank: That’s precisely the point. I am temperate because that strengthens the policy argument: if this happens in one of the better-run institutions, then it’s not a case of let’s go after the bad guy. You have to have rules for everybody.

Clift: The president’s income-disclosure statement shows he has almost a $1 million with JPMorgan. Is that an issue?

Frank: No, why should it be? That’s silly.

Clift: Jamie Dimon, considered the king of Wall Street, survived challenges to his leadership. How does this affect him?

Frank: It’s going to undercut his position. He will take a backseat for a while.

Clift: What about you? This is your legacy, and you’re going to be there to fight for it certainly until January.

Frank: It strengthens our argument, helps us explain why we’re doing this and what we’re doing. And it means this: if President Obama is reelected as I believe he will be, a year from now this bill will be in solid shape. This will strengthen the people who want the regulations to be tough.

Clift: The average citizen must wonder why it takes almost a president’s full term to get rules in place after he came into office experiencing this meltdown.

Frank: It’s a complicated thing. FDR worked on this. They were passing laws in ’40 and ’41, and getting them implemented. Yes, that’s the nature of democracy. And we could not anticipate—and this is a big part of it—Republicans refusing to provide adequate funding for the agencies that monitor this. That’s a major problem. They say $300 million is too much, $2 billion is not. The agency in charge of this has $300 million.