On Mother’s Day 2020, 49-year-old Suzanne Morphew went missing in Salida, Colorado. The mother of two adult daughters, Suzanne is the wife of my first cousin and childhood hero, Barry Morphew. Though Suzanne’s body has not been found, Barry has been charged with her murder. He is out of jail on bond, and goes to trial later this year.

Barry is a few years older than me, roughly the same difference in age between his father Rodger and my own father Joe. As Joe grew up idolizing Rodger, I was raised to revere Barry. It was easy to do—Barry was handsome and charismatic, a gifted and accomplished athlete. I kept the newspaper article announcing high-schooler Barry being drafted by the Toronto Blue Jays on my bedroom wall until I left home for college.

Barry lived as a child near Alexandria, Indiana, not far from where my dad grew up with his 12 brothers and sisters. I myself grew up in Hot Springs, Arkansas, where I lived with my mother, her husband, and their two children. Barry and I were both raised in religious households, a situation that led to much strife in my home and has led to my being largely estranged from both sides of my family.

The long injury of my evangelical childhood has proved too traumatic for me to overcome in my family’s presence, largely because they remain evangelical. It has taken many years to see that I want an apology for being conceived by them, for being programmed by them, for being of them. Since that is an unreasonable expectation, I am learning to let go.

Before I realized my need to be free of that world, I met Suzanne Morphew in 2012, at a family reunion in Indiana. None of the extended Morphews had been able to attend my California wedding in 2009, and since my wife Lauren was pregnant with our first child, I thought it was a good time to introduce her to the clan. We had a pleasant, slightly tense day (the older my father got, the more he loathed being with his siblings), and then Barry invited Lauren and me to follow him in his Porsche Cayenne to his impressively large compound nearby.

My abiding admiration for Barry prevented me from anticipating what followed. After showing us around his spread, Barry, Suzanne, Lauren, and I sat in Barry’s living room, chatting. Suzanne was kind and warm. Then, as Lauren and I started to say our goodbyes, Barry turned to his wife and said, “Would you share your testimony?”

Suzanne’s expression was that of a child ordered by her father to perform a daunting task. She pulled up her ottoman and dutifully recounted the story of her struggle with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, of her doctor telling her that she could not have another child, and of the remission and “miracle baby” that followed—all of it flowing from Suzanne’s unwavering faith in Christ.

Though Lauren and I were greatly moved by Suzanne’s story, its command-performance quality put us on guard. Because of my evangelical training, I knew what was coming next. Barry thanked Suzanne for telling her story, then looked at me and said, “Jason, do you believe in God?”

“Sometimes,” I said truthfully.

Inside, I was outraged, confused. Barry knew I had been raised to perform this tawdry, salesman-esque presentation. Every Wednesday evening of my mid-teen years, I went door to door in the neighborhood around Second Baptist Church of Hot Springs, asking if the poor inhabitants had accepted Jesus as their Lord and Savior. The evangelical “call” is to spread the Good News, so that everyone has the chance to make the choice to save their soul. I was the last person who needed to be informed of the evangelical stakes, via the evangelical process.

Then I remembered the arrogance of “witnessing,” the lie an evangelical has to tell himself in order to believe that the person he seeks to “save” has not heard the Jesus pitch 1,000 times. I recalled the centuries-old fantasy some evangelicals indulge, where they are noble missionaries educating ignorant savages about the only thing that matters. I suspect that in Barry’s eyes I had become ignorant because of a liberal, bi-coastal education.

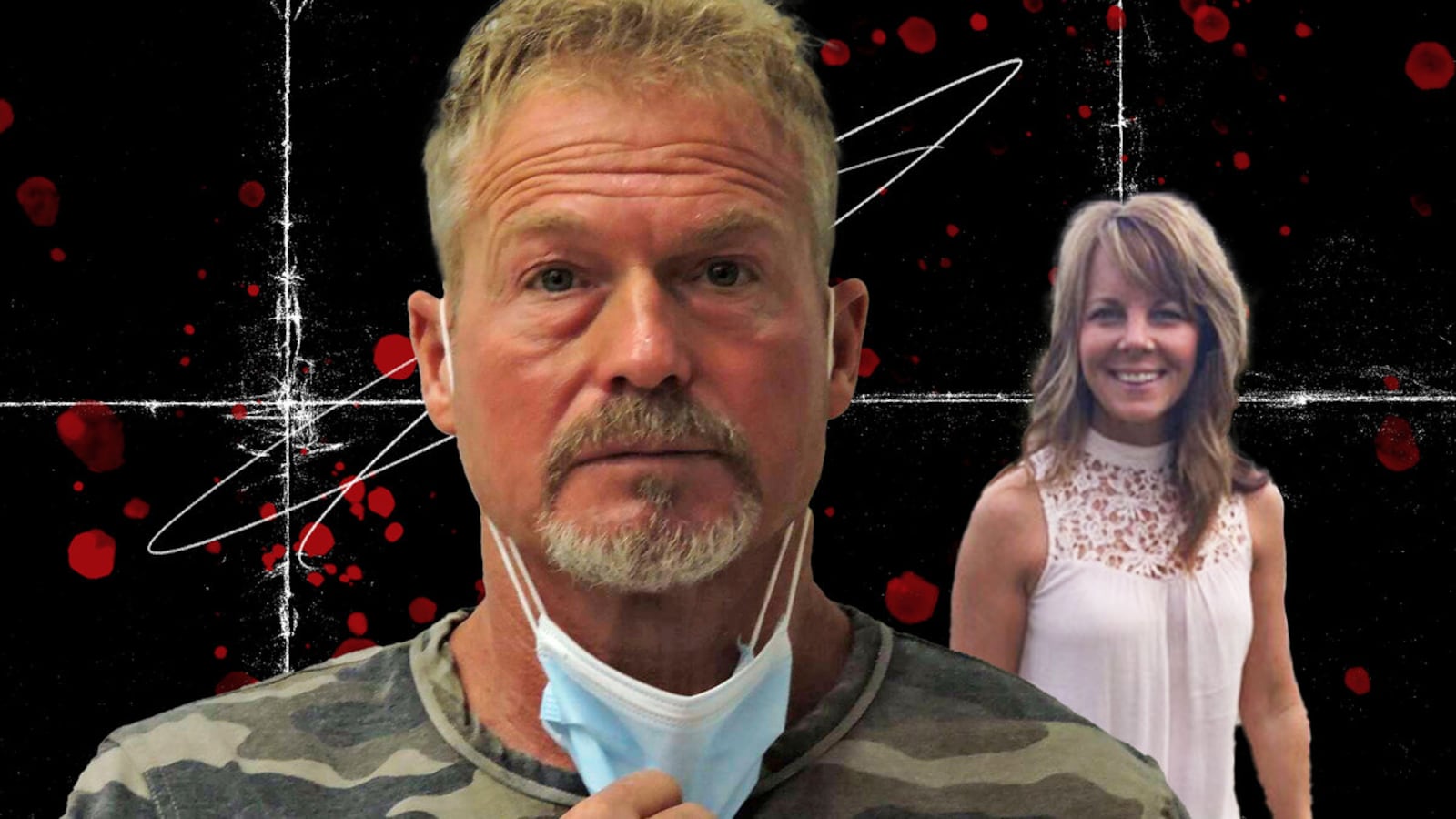

A photo of Suzanne Morphew friends and family used on missing posters and social media posts.

FacebookWhat I never realized when I was witnessing was that, by imposing myself on strangers, lecturing them about what they already knew, I enacted a kind of violence on them. I interrupted precious leisure and family time to impose a memorized message that took no account of my audience’s individual experience. I was a robocall made flesh. It is a miracle I was not shot.

Growing up, I never heard an authority figure explain how to bring back to Jesus someone like the person I have become. I still have not met anyone who has swung as completely from one end of the spectrum to the other, who once marched on the Arkansas capitol to demonstrate against abortion rights and who now takes his Jewish children to masked protests against police brutality in downtown Los Angeles.

When it was clear I was not interested in being saved again, Barry leaned back in his chair, narrowed his eyes, and said, “Jason’s a good guy.” He said it like the question had been up for debate, like he was an authority on the matter. Like he was God.

When my father died in 2018, I had a disagreement with relatives about details of an obituary, which led to my publishing a correction in the local paper. This experience inspired me to set up a Morphew “Google alert” to keep track of information published about my people.

That is how I learned first about Barry and Suzanne’s move from Indiana to Colorado and, after that, about Suzanne’s disappearance. I sent a letter to Barry, expressing my sympathy, offering my help. He texted his thanks, and in December 2020 he texted me a photo of himself and his daughters smiling next to a Christmas tree.

Then, in May 2021, Barry was arrested for allegedly murdering Suzanne. Soon after, I learned that Barry had also been charged with casting his missing wife’s mail-in ballot in the 2020 presidential election for Trump. According to an arrest affidavit, he has admitted to voting illegally, even as he has steadfastly denied murdering his wife. The roughly 130-page affidavit details his evolving alibis, his business maneuvers, and his narcissistic manipulation, but what I find most fascinating is what I have come to regard as Barry’s theology.

Not only did Barry suggest to the FBI that if anything bad happened to Suzanne, it may have been God’s punishment for her recent behavior (after surviving cancer a second time, Suzanne had begun drinking wine and taking CBD, and she was having an affair with a former high-school classmate from Indiana). He also told a Colorado TV news reporter that “Suzanne trusted the Lord, and if one person got saved from this, she would think it was worth it.”

That quote blew my mind—less because of its blithe cruelty than for its brave theological accuracy. Barry articulated a truth about evangelical Christianity that he was uniquely situated to discover: Absolutely anything that brings a soul to Jesus is justified, including uxoricide. God’s sending his son Jesus to earth to pay for every sin—including Suzanne’s murder, which would have been on Jesus’ mind while dangling from the cross—renders murder meaningless compared to its potential to confer upon a non-believer eternal happiness.

If that reading of Barry’s quote seems heartless, I encourage you to correct it from an evangelical theological perspective. Saving souls is all. As one of Barry’s last texts to Suzanne attests, eternity in heaven mocks the comparative nanosecond of earthly existence.

If Barry killed Suzanne—a human woman on earth, who seems to have sought happiness here and now—I suspect he would have done it because he thought she was losing sight of heaven, losing sight of God, losing sight of death. If he dismembered and buried, burned, or drowned her body, I believe he would have done it because “the husband is the head of the wife, even as Christ is the head of the church.” If he did it, he seems to have subsequently tried to justify or at least explain it with his faith.

Who better to be known as prophet for the MAGA mob?

It is my hope that Barry’s adamantine faith, combined with his current existential crisis, will inspire him to further revelations—that, even if he must be separated from the general population, he will continue to spread his gospel of blood and ice.

Now I seek to admire him in a new light—as the spiritual force that frees me from my past.

Editor’s note: Barry Morphew is charged with first-degree murder, tampering with a corpse, possession of a deadly weapon, and attempting to influence a public servant. He has pleaded not guilty.