During the 1977 NBA Finals, Bill Walton averaged over 18 points, five assists, three blocks, and an inconceivable 19 rebounds per game. His sublime performance—which led the Portland Trail Blazers to a 4-2 series defeat against Julius Erving’s Philadelphia 76ers—is widely considered a capstone on perhaps the most dominant individual peak in the history of post-merger NBA basketball.

It was the pinnacle of a two-year run, impressive enough to overshadow the relative absence of accolades for a player of his stature caused by chronic injuries, and it helped him clinch an easy ticket to the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Yet, Walton’s Finals MVP was merely the second-most awe-inspiring use of his body. As an undergraduate at UCLA In 1972, Walton stood with his fellow Bruins against the Vietnam War, at a time when such dissent was shocking and dangerous (and well before history would prove his actions correct).

Walton was part of a campus protest movement that marched through city streets and blockaded the campus quad. Walton, and 51 others, were arrested for their resistance.

It was the first widely publicized example of Walton’s uniquely conscientious life, a young man who used his earliest days in the spotlight to advocate for causes beyond his own well-being, a 6’11” radical willing to leverage his presence and sacrifice his frame for causes far bigger than ball.

Walton chronicles his activism in Back from the Dead, his 2016 memoir that spans his life and career. In it, he wistfully remembers cheering a student fire-hosing a police battalion from the upper floors of UCLA’s Haines Hall, engulfing the student in “a warm, welcoming roar of approval.” He describes with great pride how the LAPD—a department who needed far less than a fire hose to justify cracking heads and slapping handcuffs—arrested him “as well as fifty-one of my very good friends.”

UCLA's basketball center Bill Walton carries a large piece of wood to use in building a barricade outside the administration building of the UCLA campus on May 11, 1972.

APWalton was defiant even when John Wooden, UCLA’s men’s basketball coach and a lifelong hero, reamed him out for his civil disobedience. “Look, you can say what you want,” Walton recalled. “But it’s my friends and classmates who are coming home in body bags and wheelchairs. And we’re not going to take it anymore. We have got to stop this craziness, AND WE’RE GOING TO DO IT NOW.”

Dave Zirin and Frank Guiridy delved further into Walton’s activism after joining the Portland Trail Blazers. Citing Walton’s open letter condemning “the imperialist and genocidal wars that have been waged against the people of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam; and now possible U.S. role in a war in the Middle East,” the writers argued that his evolving sense of the world—and his place in it—expanded beyond domestic issues of race and an increasingly unpopular war.

Then and now, this was an almost uncanny level of dissent from a men’s pro athlete, even more so coming from a white man.

Just weeks ago, hundreds of UCLA student protestors, encamped on the same grounds Walton once protested and arrested by the same uniforms that somehow stuffed him in jail cell, also demanded an end to the United States’ involvement in a brutal foreign conflict—all with hardly any support, in word or deed, from the institutional American sporting community. Using the Athletes for Ceasefire statement as a representative, albeit inexhaustive, survey of high level American athletes, active NBA players have been completely silent on the genocide in Gaza.

Of course, Walton’s beliefs shouldn’t be flattened so it aligns with the pro-Palestinian student protests on campus today.

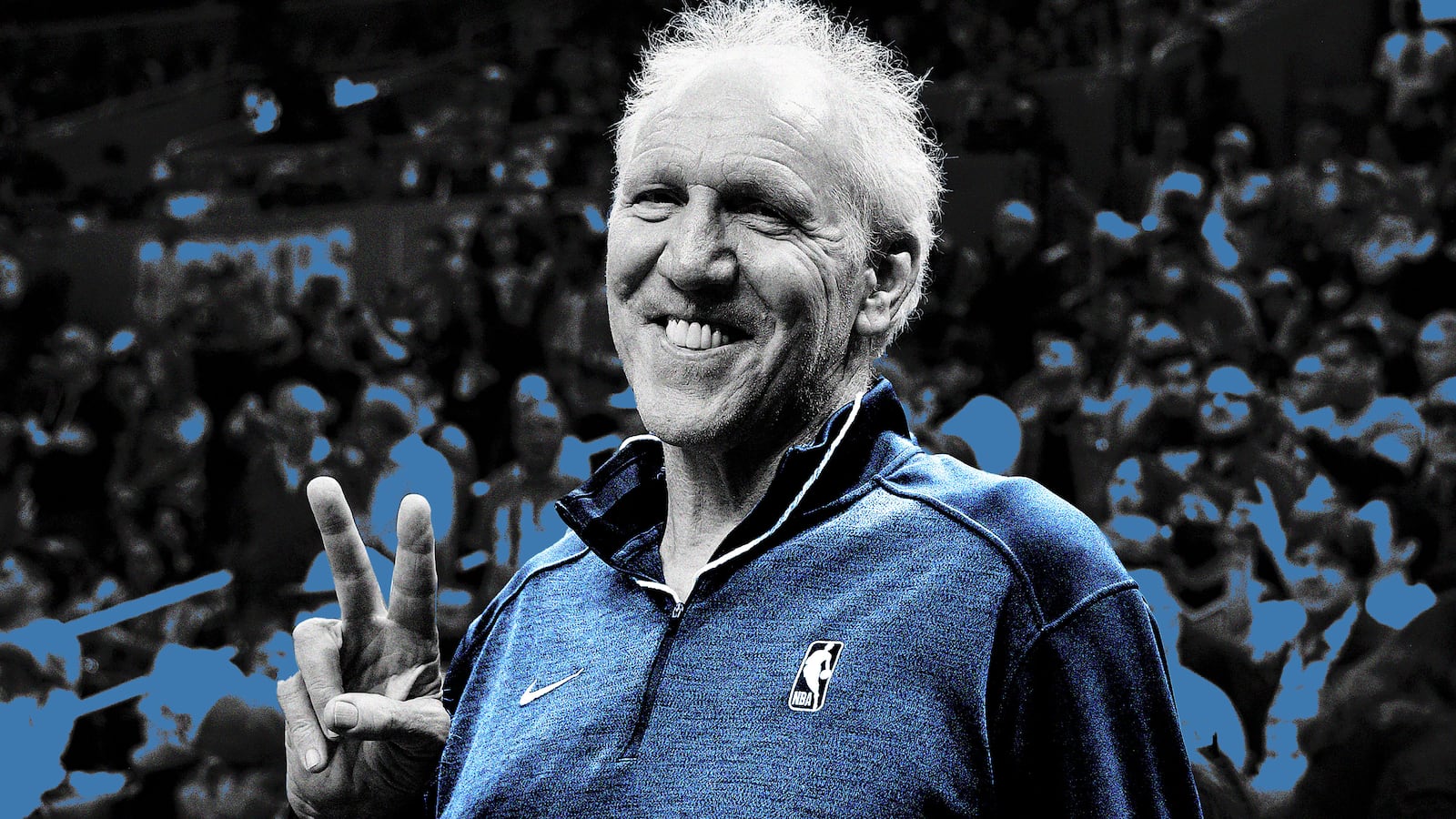

Bill Walton

GettyWalton’s most open discussion of Israel was seen in the 2016 film, On The Map—a Miracle on Ice-styled celebration of both Israel and its 1977 Eurobasket national team’s victory over the Soviet Union.

Nakedly, On The Map is a jarring watch—not just because I watched its heroic framing of a nation currently responding to the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks on its people with a violent response many magnitudes more severe. But Walton—who despised the militarism of the United States and the former Soviet Union manifested in the Vietnam War—refuses to apply the same reasoning to Israel, even as the film distinctly positions the occupying nation not as an apolitical entity but a Cold War proxy. Were Walton sticking to sports in this film—and to be clear, he does not—the basketball he raves about cannot possibly be disambiguated from the socioeconomic conditions of a country that gives some of its most gifted hoopers an honest chance at competing around the world, while forcing other promising athletes to compete for meager allotments of food and water for their survival because they were born of different ethnicity and the other side of a weaponized wall.

I would love to have had the opportunity to ask Walton if he’s considered any comparisons between the current campus activism at his alma mater regarding Palestine-Israel and his stance in Vietnam and to hear whether the last eight months of massacres led him to reconsider how he discussed the nation’s geopolitical position. But fortunately, Walton didn’t just leave us with just his stance on the issues, but his principles beyond them.

Former NBA player Etan Thomas remembered Walton’s ability to apply a historical struggle to a more modern context—for him, the former Washington Wizards’ opposition to the Iraq War. “(Walton) came up to me after a game and told me that he had the utmost respect for the position I took and the way that I took it alone,” Thomas shared from his Instagram. “Then he told me a few stories when he was at UCLA and stood on his principles especially against the Vietnam War and how a lot of ppl didn’t like it.”

“He told me to always stand up for what I believe in.” Again, a value Walton brilliantly embodied through his public life, and one that ripples from his moment to ours.