As Capitol Hill residents have cordoned off several city blocks and taken over a police precinct to set up the “Seattle People’s Department” in their "No-Cop Co-Op," President Trump has threatened to use force to take back CHAZ if the city does not reassert control.

Fifty years ago, an African-American mayor of the nation’s eighth largest city took similar action in the midst of a full-blown street war between police and black nationalists. The day after one of the deadliest nights in Cleveland history, Mayor Carl Stokes ordered the white police and national guardsmen to evacuate a six-mile region and allowed only Black cops and neighborhood “peace patrols” to remain to reestablish order. The tactic worked. While some looting and firebombing continued, no further lives were lost and calm was quickly restored.

The move by Stokes, however, was his political death knell. As he put it in his autobiography, his sealing off the area from white police “did unleash what had been latent race hatreds that had been smoldering since the election.”

He was verbally slandered by police over car radios. Many called for his removal and placed posters with images of Stokes and city Safety Director McManamon on them in precincts around the city: “WANTED to answer questions for the murder of three policemen."

Stokes won the mayoral election of November 1967 and became the first African-American elected mayor of a major U. S. city, celebrated on the covers of Newsweek and Time. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had made a cause of Stokes’ election, coming to Cleveland frequently in the last year of his life to register and energize voters.

King told reporters in Cleveland that he wanted “to transform that moral power [of the civil rights movement] into political power so that we bring about the necessary political reforms that will solve the problems that we face.”

King did not call it “black power,” but that is what he was talking about. It was a concept championed by Malcolm X, Bobby Seale of the Black Panthers, and Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael). Dr. King was pushed especially by Carmichael to become more confrontational about the pursuit of black power. Malcolm X had laid the groundwork when he came to Cleveland in April 1964 to deliver his “ballots or bullets” speech, which historians consider one of the top-ten most influential speeches of the 20th century.

Malcolm X encouraged Blacks to own rifles and shotguns. “The only thing that I've ever said is that in areas where the government has proven itself either unwilling or unable to defend the lives and the property of Negroes, it's time for Negroes to defend themselves,” he declared in Cleveland. “Article number two of the constitutional amendments provides you and me the right to own a rifle or a shotgun. It is constitutionally legal to own a shotgun or a rifle.”

The Black nationalists in Cleveland formed rifle clubs named after the slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers. In turn, they were hounded by the FBI through its COINTEL program.

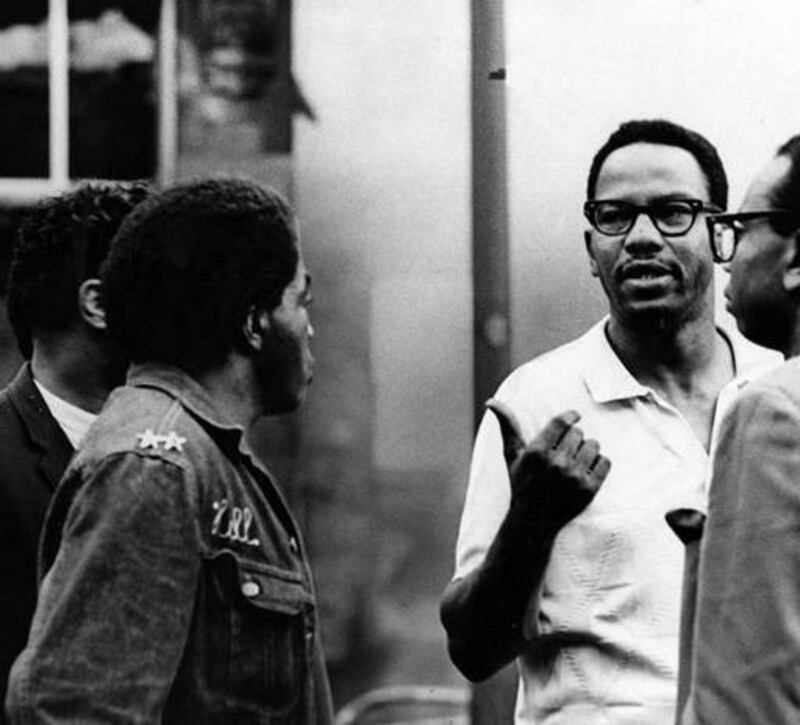

In July of 1967, Fred “Ahmed” Evans, the leader of the militant Republic of New Libya faction and a Korean War veteran, met with Dr. King and agreed to support Stokes in his bid to become mayor. Evans even registered and voted, though he told newspapermen that King was a “fool.” Evans believed that King would eventually pay with his life for his civil rights activism and his recent stance against the Vietnam War.

When Stokes was elected, it was a day of jubilee. Black power had seemingly triumphed. But just five months later, as predicted by Evans, Dr. King was gunned down in Memphis. While Evans expected an uprising, Stokes managed to keep Cleveland’s Black neighborhoods peaceful on that April 1968 night.

But that July, the streets exploded. The years of police abuse and violence had reached their boiling point. Evans, who had been systematically harassed and beaten and was evicted from his places of business and his living space, decided that it was time to fight back. He armed himself and his group with long rifles and armor-piercing bullets and planned an uprising. His plot was discovered by the FBI and Cleveland police.

On the evening of July 23, 1968, when Stokes happened to be out of town at the time, Evans thought he was being surrounded by police and then shots rang out. It is still not clear who shot first, but the gun battle raged for several hours deep into the night. The scene was one of horror. Three nationalists, two civilians, and three patrolmen were killed at the scene. More than 15 officers were badly wounded.

Stokes, still in his first year in office, faced a calamity. He feared a bloodbath and Black leaders pleaded with him to remove from the Black neighborhoods all white policemen and the National Guard troops that Ohio’s governor, James Rhodes, had called up.

The commander of the Guard, Major General Sylvester Del Corso, strongly objected to the removal plan. Stokes persisted.

Citizens had reason to fear police retaliation. They knew what later was shown in the autopsies of the three policemen who had been killed in the attack: of the three, two had blood alcohol levels consistent with the recent consumption of eight to 10 shots of whiskey or a similar number of beers.

When they were killed, sometime after 8:20 p.m., these officers had been on the job since 3 p.m. Black residents well understood that the police condoned the prevalent culture of drinking while on duty in their neighborhoods.

With the police removed, scores of volunteers walked the streets encouraging everyone to go home. Some looting continued but the shooting stopped. The next day, Stokes felt the red-hot crisis had passed and he began to let police and national guardsmen back in, though the peace patrols continued to help keep the peace.

“Black Power” in 1968 became “Black Lives Matter” in 2014 and now also “Defund the Police” in 2020. To be sure, reforms have been attempted over the last 50 years, but the continuing sad state of relations between police and African-Americans calls for new thinking, a reimagining of the entire structure of peace-keeping in our cities.

Maybe Stokes hit on the right idea when he saw that the use of peace patrols made up of citizens from the neighborhood should be the norm rather than bowing to the knee-jerk response of unleashing masses of militarized police forces. In the days following the Cleveland shootout, an extremely precarious situation, this prescription saved lives.

The alternative seems to result in an unending cycle of unnecessary lethal confrontation and escalation. We see it day after day, year after year.

Case in point: Del Corso, the National Guard general who opposed the removal plan of Stokes, was the senior officer in charge two years later when Governor Rhodes again called them out, this time to put down anti-war protests on the campus of Kent State University.

As history marks, four students were shot dead and multiple others were wounded by the National Guard. President Trump should take note.

James Robenalt is the author of four nonfiction books, including Ballots and Bullets, Black Power Politics and Urban Guerrilla Warfare in 1968 Cleveland (2018).