If you grew up in the Northeast in the seventies and early eighties, as I did, then, chances are, you know Friendly’s.

In Webster, the small Massachusetts town where I spent much of my childhood, our local branch of the restaurant chain, with its candy-cane-colored signage, written in perfect cursive, rose high above a busy main street, like sunshine breaking through the clouds. Conveniently located on the way to my house from school, the bank, the supermarket, and Dugan’s Drug Store, Friendly’s promised a fun family outing, even as my two siblings and I squabbled incessantly and drove our parents insane in the process. But there’s something about an ice cream cone that always made everything OK. And that’s how we always ended the meal, each picking one up from a little window that opened out into the parking lot. To this day, black raspberry ice cream with chocolate jimmies (that means sprinkles in Red-Sox country) reminds me of riding around in our Oldsmobile on a warm Saturday night.

If my parents grew up in this country, they would have been able to enjoy Friendly’s as kids, too. Friendly’s was started in 1935, in the middle of the Great Depression, when brothers S. Prestley and Curtis Blake, couldn’t find a job. Their mom, Ethel, had heard about a new freezer technology and suggested her boys give it a try. “Business for the boys,” was how the mom put it in a letter to alert her husband, Herbert, who was traveling for work at the time, as a vice president for sales at the Standard Electric Time Company.

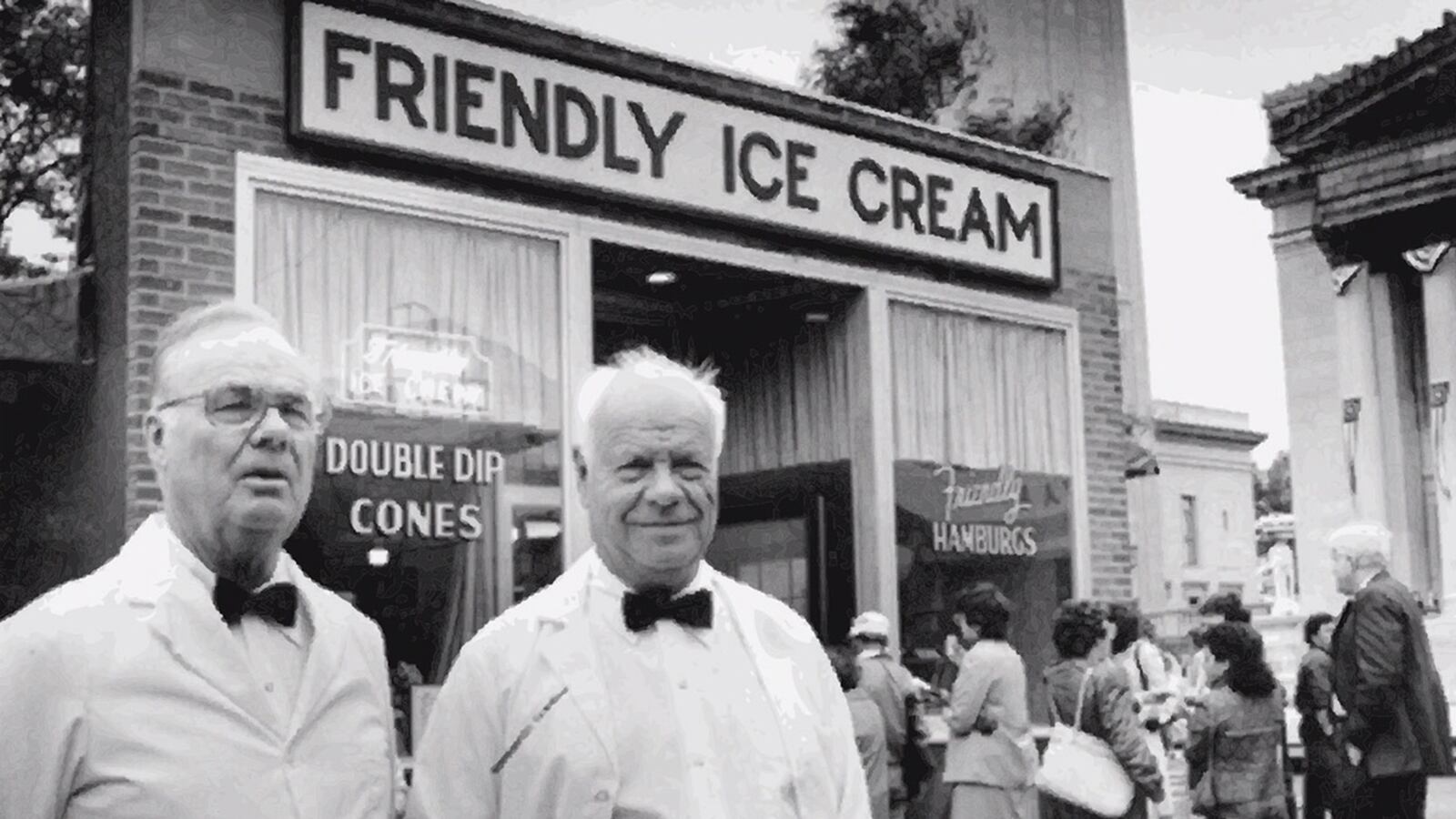

It all made sense: “Our whole family had a passion for ice cream,” says Curt. Curt and Pres, as the brothers have long been known, borrowed $547 from their parents and set the price of a a double-dip cone at five cents, which was half as much as what the competition was charging. It took them all of six weeks to figure out the logistics, and on a 90-plus-degree July afternoon, they had their grand opening in Springfield, Massachusetts, and a line quickly formed, filled with people hankering for a cool treat and a bargain.

Pres credits Curt for the name Friendly Ice Cream. “We were two friendly guys and we wanted our little store to be a friendly place,” he explains in his autobiography, A Friendly Life. One would stay late to prepare the ice cream for the next day; the other would come in early to serve customers. Because they never needed a car at the same time, they started off sharing a used 1928 Ford Model A they bought for $40.

“We had different skills that meshed beautifully,” says Curt, who now lives with his wife in West Hartford, Connecticut. Curt focused on the employees, and later, with the expansion, the design and build of new stores; Pres, the financials. Only once did they fight over whose turn it was to do the dishes, but they got over it and agreed not to fight again, over a “stupid thing” and they set up a system for chores. “It was good to work with someone I could trust and depend on,” Pres says.

For direction, they relied on their customers. When winter hit and they needed to sell something besides ice cream, they polled people who showed up at the shop; coffee and burgers won out. Eventually they added grilled cheese sandwiches (to satisfy Catholics customers on Friday). Over the years, they created other items, such as the Fribble and the Big Beef, which became almost as famous as Friendly’s itself.

During their 40-or-so years at the helm, the brothers also took pains to show appreciation for their patrons and treated them right. “Curt and I always thanked every customer as they left the store. We also made it a policy to replace the cone if a child dropped his ice cream. It made the parents happy as well as the child,” Pres tells me.

They opened the second store five years later and additional locations followed. For each, they bought the land and built the shop from the ground up. They designed the stores themselves, sent their own people to supervise the construction and used their own trucks. They even ground their own meat for the burgers. If they didn’t have the money in cash to buy something, then they didn’t buy it at all. “I realize these are old-fashioned methods,” says Curt. “Now you borrow a pile of money, you take a lot of risks and you build the thing up in 5 or 10 years instead of 45, and you sell it for billions of dollars instead of millions. That’s the quicker way to do it.” But it wasn’t their way back then. “We were very proud that all of our stores were paid for by the time they opened,” says Pres. “It gave us a big advantage in being able to grow.”

As baby boomers got married and had families, Friendly’s boomed, too. By 1979, when the brothers retired and sold the company to Hershey Food Corp. for $162 million, the chain had around 600 properties, some as far west as Ohio. Later, at its peak, that number grew to 740.

But over the decades, as the old businesses practices gave way to the new (and an “’s” was added to Friendly along the way), Pres and Curt weren’t so, well, friendly to each other anymore. These days, Pres (who just turned 103) and Curt (who is 100) don’t talk to each other much. Call me crazy, but when I found out about that, I felt kind of sad and I wanted to know what happened.

From what I can tell the brothers simply had different ideas of what retirement meant. Pres felt it was only right to be “keeping an eye on Friendly,” as he put it in his autobiography. “I wanted ‘my baby’ to be prosperous.” This meant checking in with current officers from time to time—you know, “to find out how it was doing.” But to Curt it seemed like Pres “acted as if he still owns the company,” he says.

This difference in opinion came to a head in November 2000 when the value of Friendly’s stock had fallen to $1.70, and Pres pinned the problem mostly on Donald Smith, who bought Friendly’s for $375 million in 1988. As Pres painstakingly explains in his book, he didn’t see why Smith needed a corporate jet. Pres also suspected him of using Friendly’s funds to pay for the expenses of another company he owned.

And so Pres came out of his 20-year retirement from Friendly’s and began to buy 100,000-share lots of the company. In two weeks, he turned himself into the largest single shareholder. In 2003, he launched a lawsuit against the company (which, by the way, became a case study on shareholder activism at Harvard Business School). Curt disagreed with his brother’s actions, and the two didn’t speak with each other for many years, at least not directly.

“I’m sorry my brother isn’t with me on this,” Pres told the Boston Globe, “but I’m going to keep going because I know I’m right. I’m going to keep going until I can’t go any further.”

Curtis responded, “I’m very disappointed. He was my best friend for 85 years. It would have been a nice story if we ended up best friends for our entire life.”

The lawsuit eventually was dropped when Friendly’s was sold again to another company.

The brothers have since smoothed over that rough patch, though things don’t seem to be quite the same; clashes erupt and bouts of silence follow. Meanwhile, times haven’t been easy for Friendly’s either, especially after the 2008 recession. Chain family restaurants began to lose their relevance, and, making matters worse, consumers wanted their food fresher, healthier, or with a cooler vibe.

And for many diners it just became too expensive to go out, even to Friendly’s. During the last decade, costs continued to climb, but, according to Warren Solochek, president of NPD’s foodservice practice, wages for most people haven’t kept pace. So, it was no surprise that Friendly’s declared bankruptcy in 2011, closing 63 stores overnight. But the remaining locations soldiered on, even as competitor Howard Johnson’s eventually disappeared.

What’s more, Friendly’s may be finally turning a corner. The current CEO John Maguire, who also grew up in Massachusetts eating at Friendly’s, wants to update the company while keeping it true to its roots. He also talks to the brothers often. “They’ve been great friends and advisors,” he says. “What I wanted to gain from them is what made Friendly’s so successful in the past.”

In spring, the brothers will receive a lifetime achievement award from the University of Massachusetts Isenberg School of Management in Amherst. (Established by the school’s hospitality and tourism management department, it’s known as the annual HTM Awards). While the award primarily celebrates their innovations in family dining, it’s worth mentioning that their contributions reach well beyond the restaurant industry. Despite their disagreements over how to run a business, the two seem to agree in what to do with the wealth that’s earned from it—and that is to share it with others. Each brother has contributed generously to organizations in their surrounding communities, which is why you’ll see the name “Blake” on quite a few building around Massachusetts, including the Blake Building at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, the S. Prestley Blake Law Center at Western New England University, the Herbert P. Blake Hall at Springfield College (named after their dad), and much, much more.

Pres turned 103 over the weekend, and when I asked him, a few weeks earlier, what he was planning to do, he wasn’t sure. “Ask Helen,” he said, referring to his wife. “I don’t care if it’s ignored.” I guess 103 is no big deal after his blowout centennial bash. That party was held in the replica of Monticello he built for almost $8 million near his home in Somers, Connecticut. To be clear, he built it not to live in, but as a testament to his enthusiasm for Thomas Jefferson. “I sure had a great time,” Pres tells me about that milestone birthday,

You can be certain that as long as he’s alive he’ll do what his mom always told him and his brother to do: KEEP BUSY. The emphasis, in all caps, is Pres’s, and it’s, in large part, the secret to his longevity, he insists. He makes good on that mantra, too, even to this day. Last year, when Dean Foods purchased Friendly’s manufacturing and retail arm, Pres bought 100,000 shares of Dean Foods stock. “I wanted to show my support for Dean Foods,” Pres told MassLive.com, “I want people to know that I think about Friendly every day.”

As for the restaurant arm of the brand, a new prototype restaurant rose up in Marlborough, Massachusetts, this month, amid a 150,000-square-foot entertainment complex, which, when completed, will include shops, offices, hotels, a swimming school, a trampoline park and other stuff that sounds a lot more fun than anything I ever did as a kid. The new Friendly’s will offer old-timey touches like a soda fountain area and value meals, but it will also have a drive through, outlets for laptops and cell phones, Sriracha Big Beef Burgers, and (if Maguire’s efforts prove effective) friendly service. It’s a new look and there’s a vibrancy about it that I hope will succeed in reviving the brand—and also, somehow, rekindle the special bond the brothers had long ago.