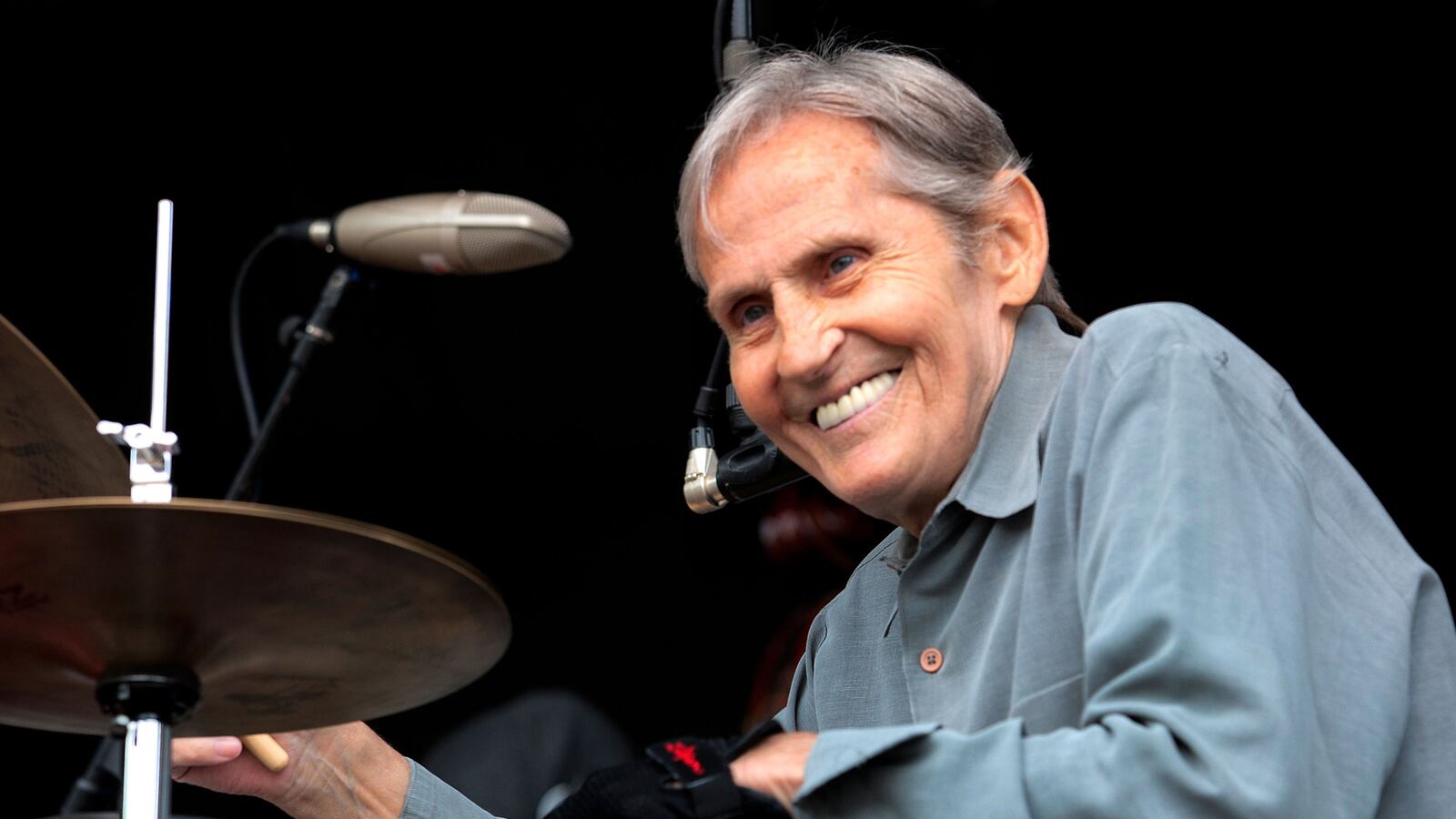

“I don’t want a biography,’’ Levon Helm told Jacob Hatley in 2007 when the young director came to Helm’s Woodstock home and broached the idea of making a film about the venerable singer and drummer’s life. Helm had no interest in exploring the past, and neither, really, did Hatley, who felt less like investigating than sitting back, fly-style, and creating a portrait of a vibrant, ailing, cranky, authentic rock-and-roll lion in winter. As we see in the resultant film Ain’t in It For My Health, which opened in New York on April 19 (on the first anniversary of Helm’s death) and later throughout the country, Hatley got all that he hoped for, and more.

Unexpected events drift in to fill Helm’s days and Hatley’s picture: the birth of Helm’s first grandchild, the opportunity to complete an unfinished Hank Williams song, a Grammy nomination for the first album he’d recorded in two decades, and a serious health scare. There is a wide array of privileged moments shown in this film: the sheer sweetness of Helm playing “In the Pines’’ for his tiny grandson, tension as Helm waits on a cold steel stool in a hospital examining room, a “who’da thunk it?” teaching moment when Helm holds forth on the venomous spurs on the legs of the duck-billed platypus, and the excruciating scene in which Helm twists in pain as a doctor inserts a tube into his nostril in order to examine his inflamed vocal chords. And there’s sheer awe whenever he sings, and that amazing voice, now banged-up and frayed, connects to the heart of an authentic America that lies buried somewhere under a million tons of junk culture.

But while biography may not have been what Helm wanted, and while biography may not have been what Hatley sought to serve, biography in the end would not be denied, and it’s the way the injured feelings from Helm’s past seep like the goo from a malfunctioning septic tank that gives the film its bite.

For those who don’t know, Helm was the drummer and one of the lead singers of The Band, a popular and influential group of the late sixties and early seventies. They leaped to legendary status when Martin Scorsese decided to tell their nearly unbelievable story (Canadian bar band to Bob Dylan, backing band to critically acclaimed innovators and international arena headliners) against the backdrop of their brilliant final concert.

That film, The Last Waltz, is widely considered the best rock-and-roll film ever made. But what that film does not document is Helm’s great anger at the break up of The Band; he didn’t want The Band to end, resented participating in the movie, and hated that lead guitarist Robbie Robertson was pulling out. Over time his feelings intensified, particularly as money became an issue; he felt he didn’t get fair compensation for his participation in The Last Waltz, and he felt that Robertson unfairly took sole songwriting credit, along with the royalties that flowed from those credits, for songs that The Band wrote collaboratively. In the ensuing decades, as money troubles and more tragic events seemed to afflict all the members of the band except Robertson, Helm’s feelings hardened.

Helm, by all accounts, was one of the world’s great spirits. He was a generous, gregarious, upbeat person whose bottomless ability to express congeniality and remember names and share the spotlight earned him affection so warmly expressed that one starts to think people are speaking not of a human but of a beloved and recently deceased family dog. And Hatley’s film captures plenty of moments of Helm’s joie de vivre: gracefully obliging his doctor’s borderline inappropriate request for an autograph, joy-riding on his neighbor’s tractor, and taking the same delight in talking to a bus driver about interstate highway connections as he does in chatting with Billy Bob Thornton about sushi restaurants and Hawaiian pot.

But as the opening line from the Hank Williams song he’s working on says, “I’m living with days that forever are gone.’’ His “unresolved feelings’’ about The Band, as Helm’s longtime friend and collaborator Larry Campbell calls them, manifest in different ways. Sometimes he battles to contain them. Asked by Billy Bob Thornton about what happened to The Band, Helm half groans. “It was a goddam screw job,’’ he says, hoping that the fog of vagueness will discourage Thornton from tapping further against the thin crust covering thirty years of acid.

At other times, they erupt. Told about the Grammy committee’s offer, Helm sneers at “that Lifetime Achievement bullshit’’ with the disdainful eloquence that could only come from one who had studied real bullshit at a tender age. “What good’s it gonna do Rick or Richard?’’ he asks, invoking the names of his late bandmates Rick Danko and Richard Manuel. And sometimes he’s just inscrutable: he displays a moment of excitement when he announces to the friends and employees in his kitchen that his album has just won a Grammy. But as the hugs and back-slaps ripple around the room, a shadow falls across Helm’s face. What’s he thinking about? Absent friends? Missed opportunities? The venomous spurs of the duck-billed platypus? Whatever it is, it isn’t victory.

There are no answers in Hatley’s film, but why should there be, if Helm himself didn’t want to find them? Instead, he gives us a portrait of a man in full, a great artist and an ordinary person who understands that he is being cornered, and who is still fighting for the best of whatever life still offers him.