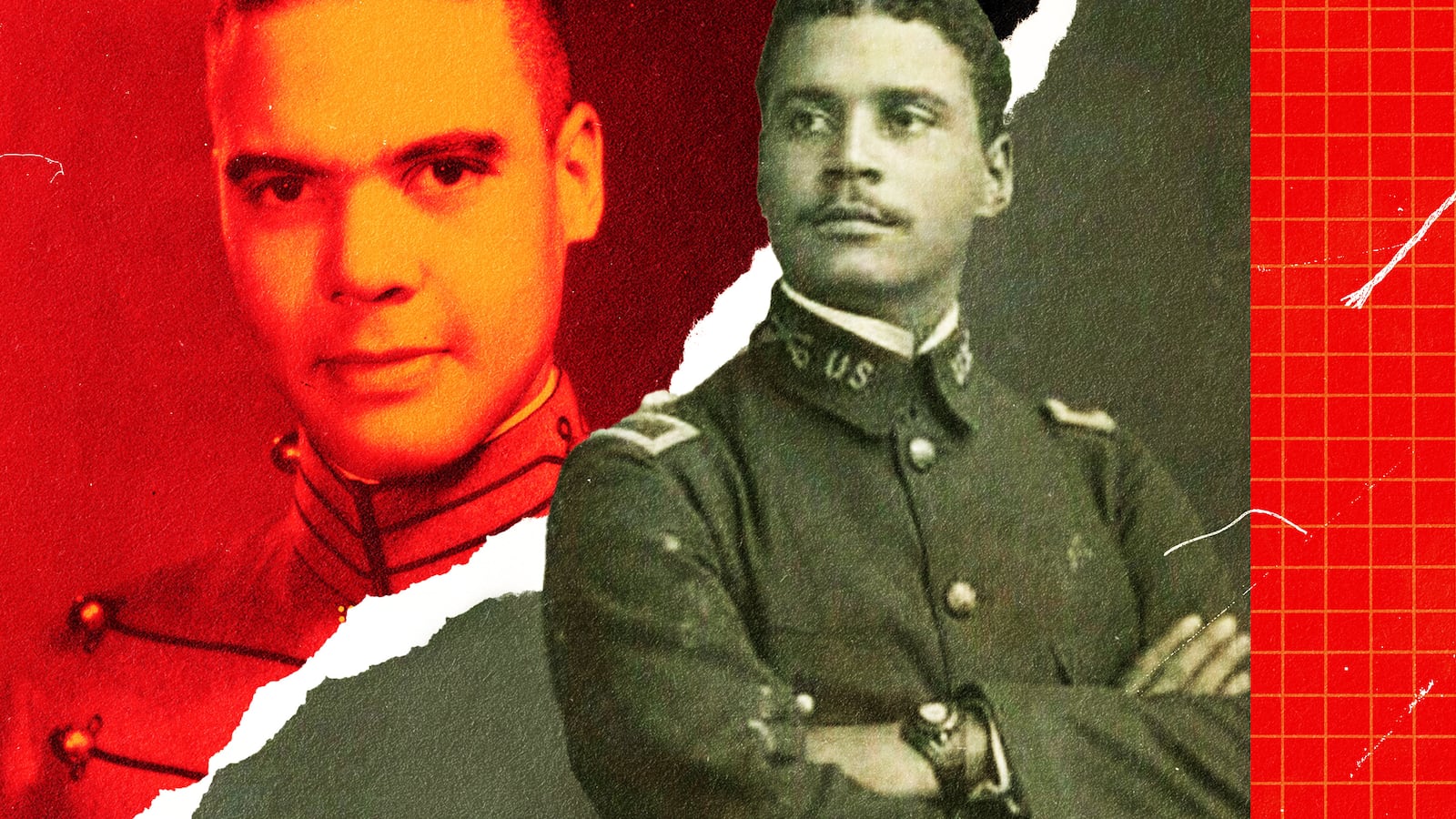

It’s not every day that you get invited to view a movie featuring someone in your family. But that is exactly what happened to me in December 2011, when I attended a private screening of the film Red Tails. This George Lucas–produced movie is based on the Tuskegee Airmen, the first Black fighter pilots in the U.S. Army Air Corps.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, Lucas had been working on the project for twenty-three years and had fronted much of his own money to make it. Red Tails ended up being the final film of Lucas’ career.

For me, it was surreal that one of the greatest filmmakers of our time had laid hands on the story of the Tuskegee Airmen—and part of my family story. The opportunity to see my family celebrated and brought to the forefront frankly blew my mind.

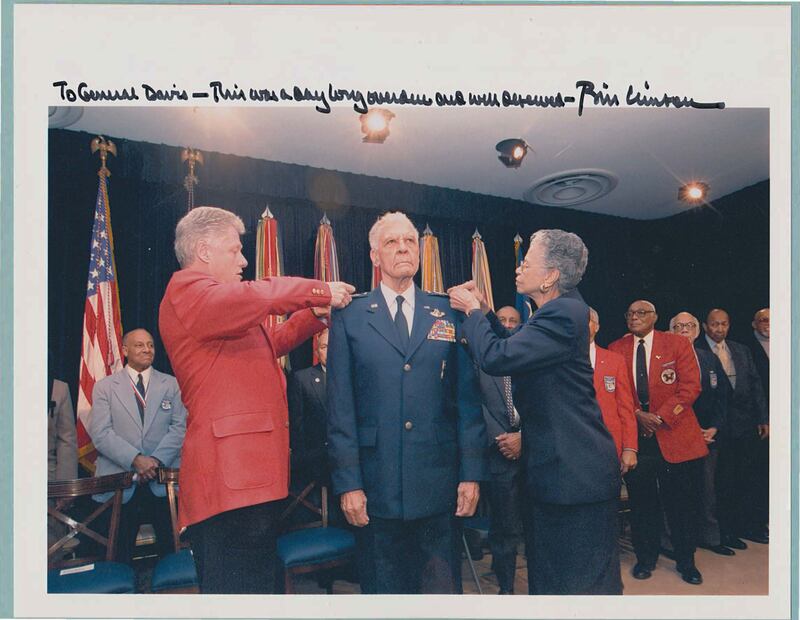

President Clinton gifted this signed photograph of him pinning Ben's 4th star to the Davis family.

Courtesy of the family/Courtesy of the familyBut Hollywood and real life rarely match up, so when some of the most basic details of the true story—such as people’s names—were changed in Red Tails, I was devastated. One of the movie’s leads, Colonel A.J. Bullard, was portrayed by Terrence Howard. The average audience member would undoubtedly watch the movie and take it all for fact, a showbiz rendering of genuine American history. But in real life, the commander of the Tuskegee Airmen, the role Bullard filled on screen, was Benjamin O. Davis Jr., my great-uncle and the patriarch of my family.

After the credits rolled, I struggled to keep my composure about what had just taken place. I felt that Ben, a real American hero, had been rendered invisible. His accomplishments, as well as those of the other Airmen, were visible, but yet at the same time had been erased.

When I shared my distress with my father the next day, his sense of resignation shook me to my core.

“Doug, one day I’ll tell you the family story—to tell you how I lived, how Ben and his father, and his father before him, lived. Then maybe you’ll see why this isn’t as upsetting to me as it is to you,” my dad said.

Over time, my dad shared the story of the Invisible Generals, a father and a son, Benjamin O. Davis Sr. and Benjamin O. Davis Jr., the first two Black generals in the United States military. Their contributions to both the military and American society are felt by every one of us on a daily basis, yet many people have never heard of these amazing men. It’s the greatest story never told.

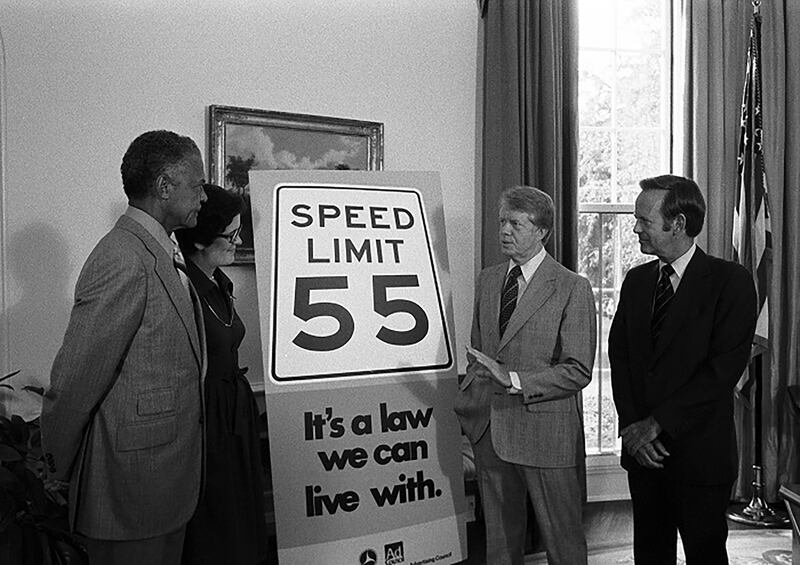

Ben in Oval Office with Jimmy Carter to unveil iconic 55 mph speed limit sign in 1971.

Courtesy of President Carter LibraryBenjamin O. Davis Sr. was born in 1880 to Louis P. H. and Henrietta Davis. Although Louis wanted Ben Sr. to follow in his footsteps and work for the federal government, this youngest son had other ideas: He wanted to enlist in the Army. In spite of Louis’s disappointment, he committed to helping his son achieve this dream. He worked his connections and reached out to his friend General Edward Logan (you might know his airport), to see if an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point could be secured. Sadly, Louis received word President William McKinley wouldn’t take up the political heat for appointing Ben to West Point, the crown jewel of the country’s military academies and where Black enrollees were still few and far between. Undeterred, Ben Sr. opted to join the Army as an enlisted man in 1898.

Ben Sr. found himself out west in the 9th Cavalry, an all-Black regiment that became the famous “Buffalo Soldiers,” and ranked up to sergeant major in a matter of months. Then, in 1901, he was recommended for a Regular Army commission as a second lieutenant of cavalry. And President McKinley, who had denied Ben Sr. entrance to West Point, ended up signing him into officer status a mere two years later.

Even in the face of racism and in a segregated military where Blacks weren’t allowed to command white troops, Ben Sr. persisted, fueled by his tenacity, discipline, and commitment to being the greatest. His patience paid off when President Franklin D. Roosevelt promoted him to brigadier general in 1940. He was the first Black general in the United States.

President Gerald Ford meets with Ben in 1974.

Courtesy of the familySimilar to the way Ben Sr. had developed a passion for horses and cavalry as a youth, Ben Jr. fell in love with airplanes and aviation. His only hope of becoming a pilot was as a military officer—and attending West Point was the most surefire way to become an officer.

Once there, in 1932, Ben Jr. quickly discovered that he’d spend the next four years without a roommate, because the white cadets refused to bunk with him.

Despite the ostracization, and against the odds, Ben Jr. graduated from West Point in 1936, and the U.S. Army’s only two Black officers until the start of World War II were a father and his son.

Much like his father before him, Ben Jr. would continue to break through barriers and transform the military from the inside out. Between the two world wars, Ben Sr. and Jr. embarked on unofficial recruitment efforts at institutions that would one day become known as HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities). Their tireless work meant that when President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave his approval for a Civilian Pilot Training Program for Blacks, with the inaugural class to launch at the famed Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, Ben Jr. was a natural choice to be their first Black leader. He received his first star, and promotion to General in 1954, shortly after the end of the Korean War, and he continued to rise through the ranks until he retired from the military as a three-star general in 1970. To top off an extraordinary military career, Ben Jr. became a Black four-star general in 1998—while he wasn’t the first, to me, he was the best. I was honored to attend that ceremony with my family, beaming with pride as President Bill Clinton pinned the star to Ben Jr.’s shoulder.

President Truman presents Ollie with a scroll upon retirement of military's only black general after 50 years of service.

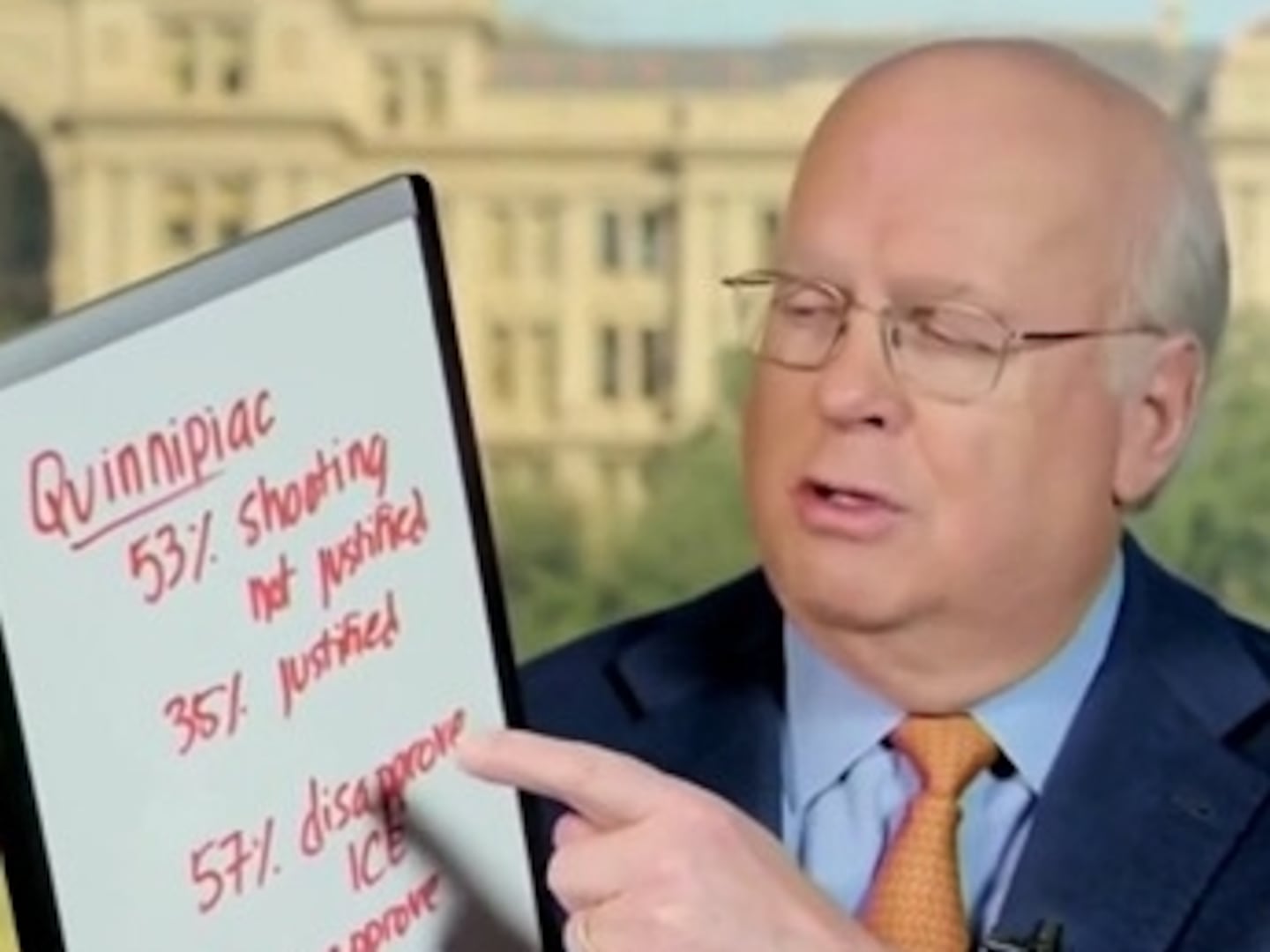

Courtesy of the familyIn the interim period before he received that long-due 4th star, he worked with the Department of Transportation (DOT) to help establish the national maximum speed limit in 1976, and developed a system to combat skyjackings, which were rampant at the time. The early implementation of low-dose X-ray scanners and metal detectors at commercial airports would evolve into what we know today as the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), in response to September 11 (And yeah, speed limits and TSA can be a hassle, but they do keep us safe!)

Between them, Ben Sr. and Ben Jr. worked directly under eight United States presidential administrations and were honored to serve this country under 13 presidential administrations.

In discovering my family’s story, I learned that some of the greatest lessons for advancing our lives forward are found in looking back and taking time to see the hurdles that have already been overcome, and to use past victories as fuel for our own dreams of what’s possible. This is what I call generational collateral.

I encourage you to celebrate and be grateful for the heroes in your family, and within your community, and to elevate their stories for the world to hear and know. Ask them to tell you their story and write it down. Whoever documents the story owns it, so it’s important to take control of the narrative. Don’t wait around for someone else to do it, because they might not tell it the way those who actually lived it remember it—as I learned the hard way at the Red Tails screening.

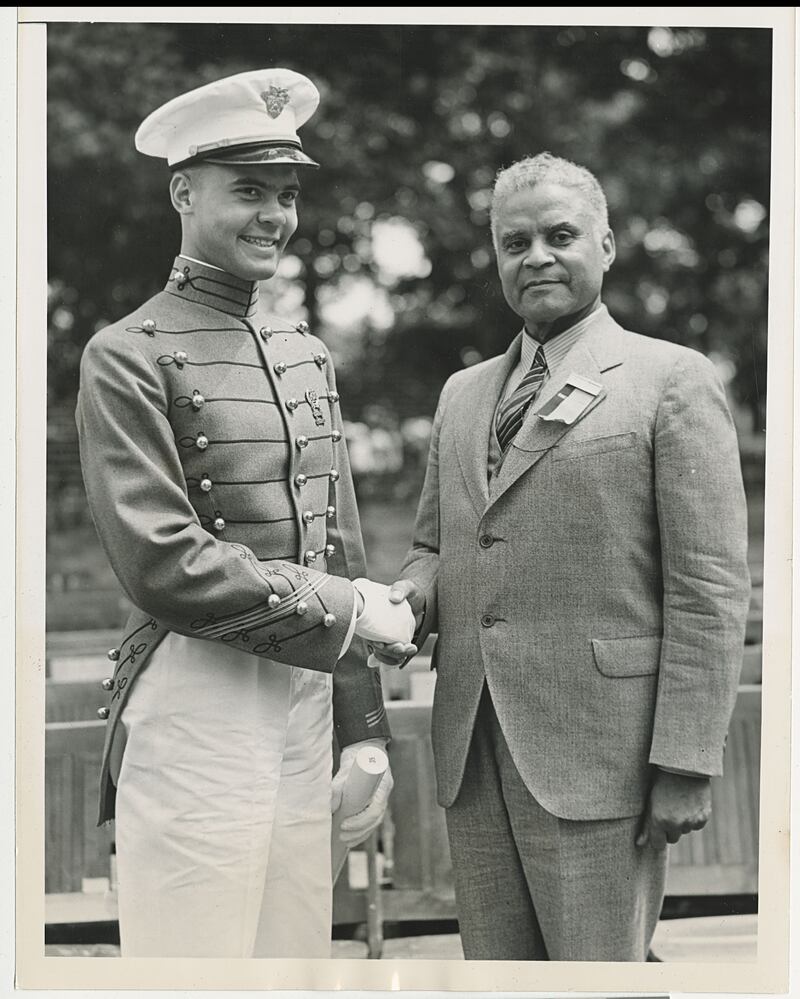

Ollie and Ben on West Point graduation day, 1936.

Courtesy of the familyEvery single family story provides insight into the tapestry of who we are as a nation: where we’ve been, where we are—and where we can go if we work together “to form a more perfect union.” By engaging with the past, and by asking our loved ones to share their stories while they are still alive to tell, we can add new dimensions to history and make those who have been overlooked—either intentionally or accidentally—become visible again.

Doug Melville, as a fifth-generation leader with a family that has worked under ten different presidential administrations, is a global head of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the luxury industry. Doug recounts his family's military service in INVISIBLE GENERALS: Rediscovering Family Legacy, and a Quest to Honor America’s First Black Generals (Atria/Black Privilege Publishing).