The barmaid had long black hair and she was sitting on top of the bar with her chest coming out of her dress and her skirt useless against the amount of legs she was showing. She had her eyes shut and her hands held out in front of her.

“Excuse me,” one of us said.

The barmaid didn’t answer.

“Ah, may I ask you something?” I said.

The barmaid frowned. “Shhhhh. I’m driving my Jaguar.”

“Oh,” I said.

A girl in bell-bottom pants played the juke box and everybody in the place, Bachelors Three on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, moved their heads with the music. Joe Namath is one of the owners of the place, and also one of its best customers.

“Well, I hate to bother you,” I said to the barmaid, “but is Joe around?”

“Not now.”

“Expect him?”

“He’s at the Palm Bay Club right now. Here, get in. I’ll drive you over.”

The guy with me, a race track character whose name is Pepe, shook his head. “You know,” he said to the barmaid, “I used to be considered a lunatic before kids like you came around.”

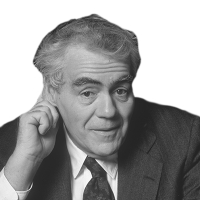

Namath was found later at the Palm Bay Club. Later, because the Palm Bay Club is in Miami. In the world of Joe Willie Namath, location and time really don’t matter. They are trying to call this immensely likeable 25-year-old by the name of Broadway Joe. But Broadway as a street has been a busted-out whorehouse with orange juice stands for as long as I can recall, and now, as an expression, it is tired and represents nothing to me. And it certainly represents nothing to Joe Willie Namath’s people. His people are on First and Second Avenues, where young girls spill out of the buildings and into the bars crowded with guys and the world is made of long hair and tape cartridges and swirling color and military overcoats and the girls go home with guys or the guys go home with girls and nobody is too worried about any of it because life moves, it doesn’t stand still and whisper about what happened last night. It is out of these bars and apartment buildings and the life of them that Joe Willie Namath comes. He comes with a Scotch in his hand at night and a football in the daytime and last season he gave New York the only lift the city has had in so many years it is hard to think of a comparison.

When you live in fires and funerals and strikes and rats and crowds and people screaming in the night, sports is the only thing that makes any sense. And there is only one sport anymore that can change the tone of a city and there is only one player who can do it. His name is Joe Willie Namath and when he beat the Baltimore Colts he gave New York the kind of light, meaningless, dippy and lovely few days we had all but forgotten. Once, Babe Ruth used to be able to do it for New York, I guess. Don’t try to tell Namath’s people on First Avenue about Babe Ruth because they don’t even know the name. In fact, with the young, you can forget all of baseball. The sport is gone. But if you ever have seen Ruth, and then you see Namath, you know there is very little difference. I saw Ruth once when he came off the golf course and walked into the bar at the old Bayside course in Queens. He was saying how f’n hot it was and how f’n thirsty he was and he ordered a Tom Collins and the bartender made it in a mixing glass full of chopped ice and then handed the mixing glass to Ruth and the Babe said that was fine, kid, and he opened his mouth and brought up the mixing glass and there went everything. In one shot, he swallowed the mixing glass, ice chunks and everything else. He slapped the mixing glass down and said, give me another one of these f’n things, kid. I still never have seen anybody who could drink like that. After that day, I believed all the stories they told about Ruth.

It is the same thing when you stand at the bar with Joe Namath.

The Palm Bay Club is a private place with suites that can cost you over $2,000 a month, and Namath lives through the winter in one of the biggest, a place with a white leather bar that many people say is the best bar in all of Miami, and a view of sun splashing on blue water. When Joe Namath came to his suite on this day, a guy he knew was taking up the living room floor with a girl. Namath went politely past them into the bedroom. Another guy he knew was there with a girl. Namath shrugged and left to play golf.

He walked around the Diplomat Presidential course in a blue rain jacket and with that round-shouldered, slouchy walk of the campuses and First Avenue. He had sideburns and a mustache and Fu Manchu beard and the thick, shaggy hair at the back of the neck which upsets older people so much, and therefore is a must with the young. I watched the Super Bowl game on television with 14-year-old twin boys, and Namath, slouchy and long-haired, came on after the game and said, “All these writers should take their notebooks and pencils and eat them.” The two around me burst out of the chairs. “Yeah!” one of them yelled. “Yeah, Joe Willie! Outasight!” the other one yelled. It was Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate all over again. Screw the adults. I knew that Joe Namath was going to mean a lot more than merely the best football player of his time.

After he finished playing golf, Namath went right for the bar. He had his money up and was ordering whiskey while he kept looking at the people with him to make sure that they didn’t get a chance to pay.

“I’m drinking a lot lately,” he said.

“Do you drink a lot all the time?” he was asked.

“I might as well. I get the name for it whether I do it or not. In college, this fella Hoot Owl Hicks and I were out one night and we had two cans of beer in the car, that’s all we had all night, and we’re coming home in one of these four-door, no-door cars. Thing couldn’t do over 35 miles an hour. But the Tuscaloosa cops stop us. They loved me. Huh. ‘Hey, Penn-syl-vania kid.’ I take the two beer cans and throw them out the car. There’s a damn hill there and here come the two sonsofbitches rolling right back to the car. I grab the two cans and throw them back up again. They come rolling down again. The cop says, ‘Hey, Penn-syl-vania kid, just leave ’em there.’ I said to the cop, ‘You’re a real piece of work. Now I know why mothers like you go on the police. Can’t get a job nowhere else.’ That did it. I got put in jail for being a common drunk.”

“Do you drink during the football season?” he was asked.

“Just about all the time.”

“What do you, taper off before the game?”

A grin spread from his mouth. His light green eyes had fun in them. “The night before the Oakland game, I got the whole family in town and there’s people all over my apartment and the phone keeps ringing. I wanted to get away from everything. Too crowded and too much noise. So I went to the Bachelors Three and grabbed a girl and a bottle of Johnnie Walker Red and went to the Summit Hotel and stayed in bed all night with the girl and the bottle.”

The Oakland game was in late December and it was for the American League championship. On Sunday morning, the Oakland Raiders football team, fresh-eyed from an early bedcheck and a night’s sleep, uniform-neat in their team blazers, filed into a private dining room in the Waldorf-Astoria for the pre-game meal. Meanwhile, just across the street in the Summit Hotel, Joe Willie Namath was patting the broad goodbye, putting an empty whiskey bottle in the wastebasket, dressing up in his mink coat and leaving for the ballgame. It was a cold, windy day and late in the afternoon Namath threw one 50 yards to Don Maynard and the Jets were the league champions. The Oakland team went home in their team blazers.

“Same thing before the Super Bowl,” Namath said. “I went out and got a bottle and grabbed this girl and brought her back to the hotel in Fort Lauderdale and we had a good time the whole night.”

He reached for his drink. His grin broke into a laugh. “It’s good for you,” he said. He held his arms out and shook them. “It loosens you up good for the game.”

In the Super Bowl game, the Baltimore Colts were supposed to wreck Namath, and they probably were in bed dreaming about this all night. As soon as the game started, the Baltimore linemen and linebackers got together and rushed in at Namath in a maneuver they call blitzing and Namath, who doesn’t seem to need time even to set his feet, threw a quick pass down the middle and then came right back and hit Matt Snell out on the side and right away you knew Baltimore was in an awful lot of trouble.

“Some people don’t like this image I got myself, bein’ a swinger,” Namath was saying. “They see me with a girl instead of being home like other athletes. But I’m not institutional. I swing. If it’s good or bad, I don’t know, but I know it’s what I like. It hasn’t hurt my friends or my family and it hasn’t hurt me. So why hide it? It’s the truth. It’s what the___ we are.

“During the season, Hudson and I were drinking a lot and he said to me one day, ‘Hey, Joe, we gotta stop all this drinkin’.’ And I said, ‘Jeez, yes. We’ll stop drinking. Let’s just drink wine.’ Hudson said, no, we had to stop all the way. Well we did. So we don’t drink and we go up to Buffalo and we lose, 37–35, and I got five interceptions. I go right into the dressing room and I tell Hudson, ‘Jeez, let’s not hear any more about not drinking.’ Then before the Denver game, I had the flu and I didn’t drink. Five interceptions.

“So we’re in the sauna before the Oakland game, the first day we were working for the game and I’m saying, ‘All right, fellas, this is the big one. Gotta win. Our whole season depends on it. Thinking about not drinking myself.’ And Dave Herman yells, ‘Jeez, don’t do that. Do anything but don’t you stop drinking. If you don’t drink, I’ll grab you and pour it down your throat.’”

Sonny Werblin, who had been on the phone, came back to the bar. He had been taking notes on a small pad. He showed the notes to Namath and spoke to him in a low voice. Sonny Werblin was the head of the Music Corporation of America and he was one of the five or six most important people in show business. He retired from MCA and bought into the New York Jets. In what clearly is the best move made in sports in my time, Werblin decided to base his entire operation on getting Joe Namath and making him a star. Last year, Werblin sold his part of the team. But Joe Namath still calls him “Mr. Werblin” and never “Sonny” and when something comes up in Joe’s life, he asks Sonny Werblin about it.

Now, Namath sat and listened to Werblin.

“How much?” Namath asked.

Werblin said something and Namath nodded and they went back to their drinks.

A few minutes later, when everybody else was busy talking about something, Sonny Werblin said, “This thing I was showing him, it’s about the movies. You see, I know he’s a natural star. I mean, look at him. He’s got the face and the eyes. Women’ll tell you, bedroom eyes. He’s got that animal sex appeal. I knew he was a star the minute I saw him. We’d been going around looking at All-American quarterbacks. They had one at Tulsa. Jerry Rhone. He came into the room, a little, introverted guy. I said, nah, I don’t want him. Never mind how good he is, I need to build a franchise with somebody who can do more than play. So we went down to Birmingham and the minute Joe walked into the room, I knew. I said, ‘Here we go.’ So what I’m doing now. I’ve got picture offers for him, but I don’t want any freaky thing just to cash in on him being a football player. I want to build a broad base for him. I heard about something just now. Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward are doing a film. We’ll pay to get into it. We’ll pay for the chance. I want him in with good actors, where he can look good. I don’t want him over his head the first time with something we’re doing just for the money. I couldn’t care about money. I wouldn’t touch a cent of anything I get for him. I just want to do it right for him.”

We had to leave the golf club and drive over to a place called the Jockey Club. Before leaving, Namath ordered a round of drinks in plastic cups and everybody got into the car with the drinks. Joe Hirsch, the writer for the Morning Telegraph, was driving.

“I’m going up to Pensacola tonight,” Namath said.

“Seeing Suzy?” somebody said.

“Yeah, I’ll see her,” he said.

“She is a lovely, very smart girl,” somebody said.

“Is she your girl?” Joe was asked.

“I like her,” he said. “She goes to college in Pensacola.”

“What school?”

“Jeez, ah, Northern Florida something or other. It’s a new college up there.”

“Is she a senior?”

“I don’t know. What is she, Joe?”

“She gets out this summer,” Joe Hirsch said.

“Uh huh.” Joe Willie Namath said.

There was a stop at a place with offices and Namath was walking through the hall and the elevator operator came after him and called out, “Mr. Namath, if you don’t stop in this office, you’ll break the heart of one of your biggest fans.”

The operator led Namath to an office where a blonde in a pale yellow dress sat at a typewriter.

“Well, hi,” Namath said.

“Hel-lo,” the girl beamed.

“How are you?” Namath said.

“Fine,” she said. “Do you remember me?”

“Of course I remember you.” He repeated her name. She beamed. “You’ve got a good memory.”

“Still got the same phone number?” She shook her head yes. “That’s real good,” Joe said. “I’ll call you up. We’ll have a drink or three.”

“That’ll be terrific,” she said. “Like my hair the new way?”

“Hey, let me see,” he said. He looked closely at her pile of blonde hair. She sat perfectly still so he could see it better. “It’s great,” Joe Namath said. She beamed. “See ya,” he said.

Walking down the hall, Namath was shaking his head. “Boy, that was a real memory job. You know, I only was with that girl one night? We had a few drinks and we balled and I took her phone number and that’s it. Never saw her again. Only one night with the girl. And I come up with the right name. A real memory job.”

When the car got to the Jockey Club, Namath, who had been in the back seat, began to get out. Pulling himself by the hands, he got up, turned his body around and came out of the car backwards, hanging on, not moving for long moments while he waited for his two knees to adjust. Now you could see why Sonny Werblin worries about the right chance at the movies for him. All the laughs of Joe Namath are based, as laughs always are, on pain. And this is a kid who has made it to the top on two of the most damaged knees an athlete ever had. His next game could be the last. So today he swings.

In the Jockey Club, he drank Scotch on the rocks. When it was time for him to leave, he asked the bartender to give him a drink in a plastic cup so he could have something in the car. He shook hands and left to get the plane to Pensacola, where his girl friend goes to a school whose name he doesn’t quite know.