When they were after him, when he was young and he had everything to lose, Lionel Stander did exactly what everybody knew he would do. He curled his lip in disdain and he brought his voice up from its bed of gravel and let the sound fill the hearing room of the House Un-American Activities Committee. He was ordered to stop shouting, but he acted as if he never heard anybody. Lionel Stander was there to make a fight.

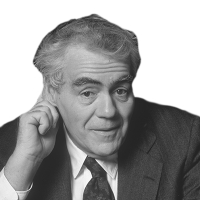

He is sixty-nine now. He is a great movie character actor who is known by too few. This is because twenty-five years of his career were stolen from him when a collection of stool pigeons said he was a Communist and a menace to the nation. Politicians wanted Stander to cower and inform. Instead, he gave them chaos. It was a display of citizenship which is on his record forever.

Lionel was in New York this week to celebrate his good part in United Artists’ tremendous hit New York, New York. And you could sit and talk with him about anything: he comes off the newspaper rewrite desks and out of the artist’s lofts of New York. But with Lionel Stander, everything always comes down to this day in 1953 when he came before the House Un-American Activities Committee at Foley Square in Manhattan.

He had been in Philadelphia the night before, appearing in the stage musical Pal Joey. In Stander’s jacket in the dressing room was the subpoena saying he had to appear at Foley Square in Manhattan at 9:00 A.M. the next day. After the curtain, Lionel got dressed and drove to New York. He arrived in the white lights of midtown at 2:00 A.M.

“This is terrific,” he said. “What a marvelous way to begin an evening.”

He went into a joint and had a drink and met a girl named Ruthie. “You’re sensational,” he told her. “Let’s go around to a few places.”

In another place there was a girl named Rita. Lionel looked at her and said: “You’re fantastic.”

With Ruthie and Rita clinging to his arms, Lionel began to use up the night. The three of them closed the Stork Club. Then Lionel took the girls uptown to an after-hours place. And then Lionel and Ruthie and Rita all got lost together and they had a terrific time. In the morning, while they all got dressed in a small but wonderful hotel room, Lionel had to tell the girls to behave because he had to go downtown to testify in the big probe of Communists.

“Oh, are you a Communist?” Ruthie asked him.

“I’ve got no time for Communists,” Stander said. “They’re political morons and all they do is compromise. I want a real revolution.”

“Oh, I’m glad you’re not some crummy Communist,” Rita said to him.

At nine o’clock on May 6, 1953, Lionel Stander stormed into the courtroom at Foley Square, striding down the middle aisle with Ruthie and Rita hanging on to him. He then took the witness chair.

A congressman named Clardy said that there had been earlier testimony about Stander’s wife being a Communist. “We will not ask you any questions about your wife,” Clardy said.

“Which one?” Lionel said. In the audience, Ruthie and Rita began to giggle.

Clardy, annoyed, said that the name of the wife was Lucy. “Do you remember her under that name?” the congressman asked.

“Yeah,” Stander said. “I remember her. Vaguely.”

Ruthie and Rita really liked that answer. They let out a howl. This made Lionel feel very good. Immediately he began to abuse the House Un-American Activities Committee. First Lionel made them turn off the television lights. Then Lionel began to talk. A river’s tide has less stamina.

“I know a lot about subversion in the entertainment world,” he began. “I know a group of fanatics that are trying to deprive individuals of their civil rights, livelihood, without due process of law. I was one of their first victims. They’re former Bundists and America-Fighters and anti-Semites.”

The chairman was banging his gavel. “No witness can insult this committee,” he told Stander.

“Why, you just asked me to tell you about subversive activities,” Lionel said. “I’m shocked. I’m not a dupe or a dope …”

On he went, roaring and rambling in the witness stand. The committee could not handle him. Stander then went on to further shock all decent people. As the News observed, “And then, before anybody knew it, he hauled in the First Amendment again.”

At the end, the committee, embarrassed, asked him to go away. They would fail to call many witnesses through fear of finding more Standers. The committee liked witnesses who broke into tears and named other people. Lionel walked out of the courtroom with Ruthie and Rita. The three went out for cocktails and lunch. He had been blacklisted from films in the late forties. Now, it would be twenty-five years before Lionel Stander would be allowed to work at his trade in this country. But all Lionel cared about on this day was that he stood up.

Now, the other night, over vodka, Stander was remembering some of this. His left eyelid droops a little. The once curly hair is becoming sparse on top. His face is paunchy. But the energy pours from him when he talks. “I’m not bitter about anything that happened to me,” he said. “I just despised a whole lot of sons of bitches. You know the worst of them all, don’t you? The guys who always disappear when the chips are down are the effin’ liberals. I like only radicals and conservatives.

“I was completely blacklisted and you couldn’t get a person to say a word for me. America was so delicately balanced at the time that my face or figure on television or in a movie would tilt America to complete anarchy. So Preston Sturges finally used me. He was no liberal. He was an aristocrat. He liked a monarchy. But he was the first one to use me after all those years. Twenty-five years. Not one of the effin’ liberals. The liberals. Dalton Trumbo is full of ———. Lillian Hellman’s book is a rip-off at eight ninety-five. Liberals. When there is a real revolution I’m going to be first commissar and there’ll be no liberals.”

He got up to answer the door. He has, if you’ll watch him in a movie, one of these great walking styles you find only in the most accomplished of actors. I first saw this stride up close on a day in 1970. There was a movie being made of a book called The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight and the director had asked me to stop into Johnny Joyce’s restaurant on Second Avenue to meet a new actor they were putting in the picture, Robert De Niro. From Joyce’s we went up to a rehearsal studio, where De Niro read lines with Lionel Stander, who had just come in from Rome. Stander worked with De Niro for a couple of hours. Then Lionel excused himself and I remember him walking down the hall toward a telephone, walking with this great, menacing stride. He was going to call his agent in Rome to tell him that De Niro, whoever he was, was going to be the greatest actor in the history of the business and the agent better grab him.

Now, at the door of his hotel suite, somebody handed him pipe tobacco. Stander took it and walked back to his seat. His wife, Stephanie, a blonde who appears to be a half century younger than Lionel, came into the room with Lionel’s four-year-old daughter.

“That’s my family planning,” Stander said. “I have children from four to forty-three. Of course it took six wives to do it.”

His wide mouth turned into a leer. “Say, if you write anything,” he said softly, “don’t say anything about that girl Rita. I think she got married.”

(June 1977)