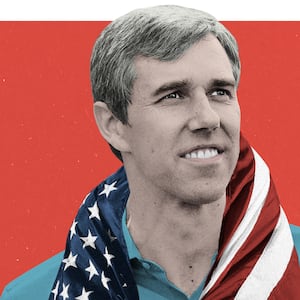

It’s rare to get a second chance to make a first impression, to go home again, to get your groove back. Beto O’Rourke has done all three as he climbed down from running for president to remain in his hometown of El Paso in the aftermath of the greatest trauma in Texas since JFK was assassinated.

From the moment the Walmart became a morgue, O’Rourke was back where he belonged, amid 680,000 residents of a community that is among the safest in the country. He stopped campaigning immediately, not to make a video of himself at a staged hospital visit, but to live among the mourners, some his neighbors, many his constituents when he served them in Congress. Vigils? He was there. A soccer fundraiser? He and his family were at the one to make up for the one outside Walmart that ended last Saturday with two coaches wounded. He donated blood, hugged everyone, spent time with those wounded while trying to save a child or spouse. He skipped the Iowa State Fair, the nation’s premier political event (and dining event too, if you like deep-fried Twinkies), where 16 other candidates bucking to win the first-in-the-nation caucuses appeared.

It was the right choice. Being in El Paso tapped into his natural gifts: empathy, wearing his heart on his sleeve, weaving policy into emotion, one hand chop at a time.

He struck a memorable note with his defiant response to a question from a reporter who, like many in the press was going through one of the five stages of coverage, going over the same old ground each time one of these unspeakable tragedies occurs. Asked what the president could do, O’Rourke snapped: “Members of the press, what the fuck?” Forgive the obscenity: We’re all swearing and crying more than we used to, and O’Rourke needed something to wake us from our benumbed condition. “You know the shit he's been saying. He's been calling Mexican immigrants rapists and criminals... Yes, he’s a racist. ”

For his part, Trump, out of the blue during his visit to trauma staff at the University Medical Center, repeated his wrong assertion that his crowd at a rally in El Paso swamped O’Rourke’s the same night. “You had this crazy Beto,” Trump said, “Beto had like 400 people in a parking lot, and they said his crowd was wonderful.” By the fire marshal count, Trump had 6,500 in attendance. O’Rourke responded, “This community is focused on healing... Certainly not crowd sizes,” resisting arguing back that his crowd was estimated to be in the thousands. What some in the El Paso community are definitely focused on is the half-a-million-dollars-and-change Trump’s campaign still owes them for that night.

With despair at how little has happened, O’Rourke recited what’s been on the to-do list for years: ban assault weapons as they were for 10 years until Republicans unbanned them, pass the bill on improved background checks which sits collecting dust on Mitch McConnell’s desk. For that to happen, Republicans would need to unshackle themselves from the tyranny of the weakened and corrupt NRA and its 5 million members—many of whom support sensible gun laws. They’re a drop in the bucket compared to the 136.7 million people who voted in 2016.

In the absence of a fully functioning president, O’Rourke filled a void and, in the process, reminded people of the man who caught the imagination of his state in his race against Sen. Ted Cruz. After losing, Beto vanished in a cloud of understandable post-traumatic election syndrome and overshared. By the time he announced for president, we’d seen him searching for himself in his pick-up truck, tending to his gums, and giving one of the most unfortunate answers to a simple question since Ted Kennedy didn’t know why he wanted to be president. “I want to be in it. Man, I’m just born to be in it,” he told Vanity Fair.

The phenom rose briefly and then fell to earth: in the polls, in his coverage, and in his fundraising—from $80 million pouring into his Senate race to $9.4 million after he announced to $3.6 million in the last quarter. Jumping up and down had lost its charm. The debates, it turns out, can hurt you but not necessarily help. If Biden seemed way too old, O’Rourke seemed too young. He’s lately been at 2 percent in the polls.

If O’Rourke has any self-knowledge, he’ll see that the presidency is not to be in favor of something closer to home, like the crucial Senate race to oust incumbent Sen. John Cornyn—and just when talk in non-smoke-filled rooms is how to thin the herd. Couldn’t some of those who looked in the mirror and mistakenly saw a president look again, and see a candidate for state office staring back? O’Rourke isn’t alone in running for higher office when his party wishes he’d aim lower—a group that includes Colorado’s John Hickenlooper, Montana Gov. Steve Bullock, and another Texan, Obama cabinet member Julian Castro, who could lap O’Rourke only if he dropped out of the presidential contest and announced first.

It won’t be as easy for O’Rourke as it was back when Sen. Chuck Schumer was begging him to run and an O’Rourke candidacy would have cleared the field, which now has about a dozen Democrats vying for the nomination. And Cornyn is no Cruz. People actually like him, or did. As a member of the Republican leadership, he bears the scars of his lock-stop support for an insupportable president in a state trending ever bluer. Although O’Rourke didn’t defeat Cruz, he gets some credit for his party flipping two congressional seats and 12 seats in the Texas statehouse in the midterms.

When O’Rourke looks back, at the end of his life, at what he did in his public career that made a difference, more than when he was a congressman, more than when he ran a race for the Senate that fell just short, and more than his so-far underwhelming presidential campaign, he will have 11 days, and counting, in El Paso. He showed up. He didn’t send his thoughts and prayers. He gave them himself.