This is the latest selection in our monthly series on The World's Most Beautiful Libraries.

PARIS––When I entered the reading room of France’s oldest public library, I let out an audible and not-too-professional gasp that was (fortunately) muffled by my protective mask.

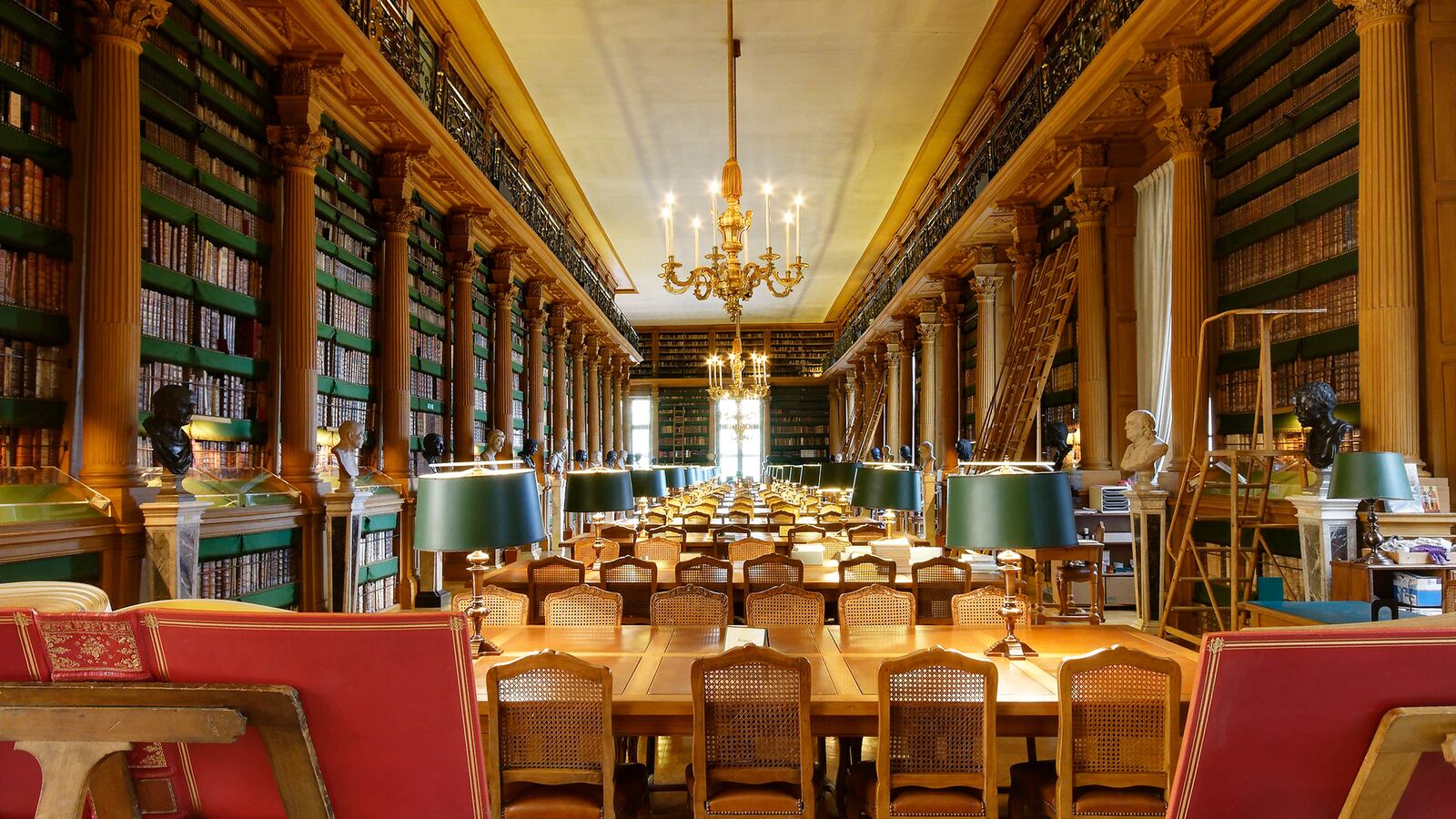

After several years of living in Paris, I have become accustomed to the city’s architectural grandeur. However, as a self-described bibliophile, I found the space’s sumptuous interior lined from floor-to-ceiling with leather-bound volumes a little overwhelming at first. Add to that the woodsy, vanilla-tinged aroma of old books hanging in the air, and I wasn’t sure whether to explore the library or just stand in the entrance and take some yoga-style inhalations.

Since I was accompanied by Florine Levecque, the library’s head of communications who served as my guide, I went with the former while hoping she wouldn’t notice the protracted deep breaths I took every few minutes. Once again, the face mask came in handy.

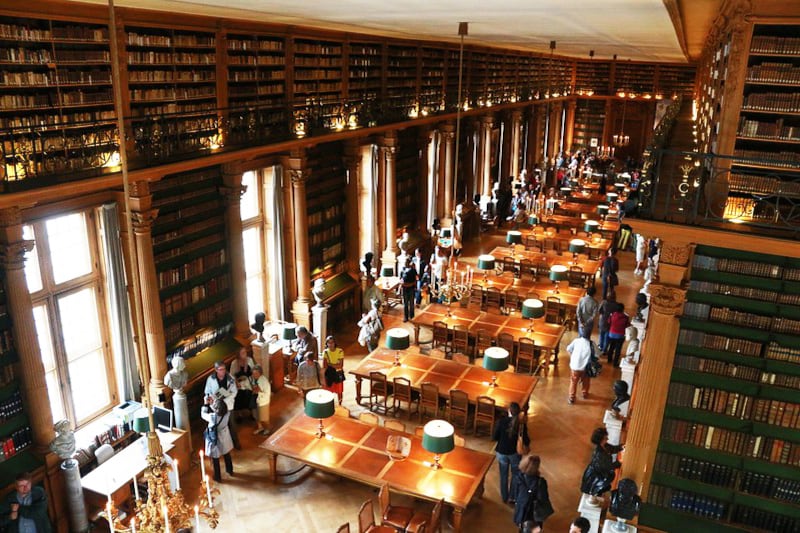

As we moved across the creaky, wooden floors in the L-shaped reading room, I would soon discover that the centuries-old Bibliothèque Mazarine is part library, part book museum, and part cabinet of curiosities.

An ornate grandfather clock made of inlaid rosewood and copper detailing has been chiming every 15 minutes since it was crafted in the 1700s, and the stunning celestial globe at the far end of the room is attributed to Vincenzo Coronelli, the renowned Venetian cartographer.

The two imposing, gilt-bronze chandeliers that dangle near the entrance once belonged to none other than Louis XV’s number one mistress, Madame de Pompadour, who had them custom made in the mid-1700s for her chateau in the village of Crécy-Couvé outside of Paris.

Levecque told me that many of the library’s riches were seized from nobles during the French Revolution and then ferreted into the library which, astonishingly, remained open even as the guillotine continued to fall at the Place de la Concorde across the river.

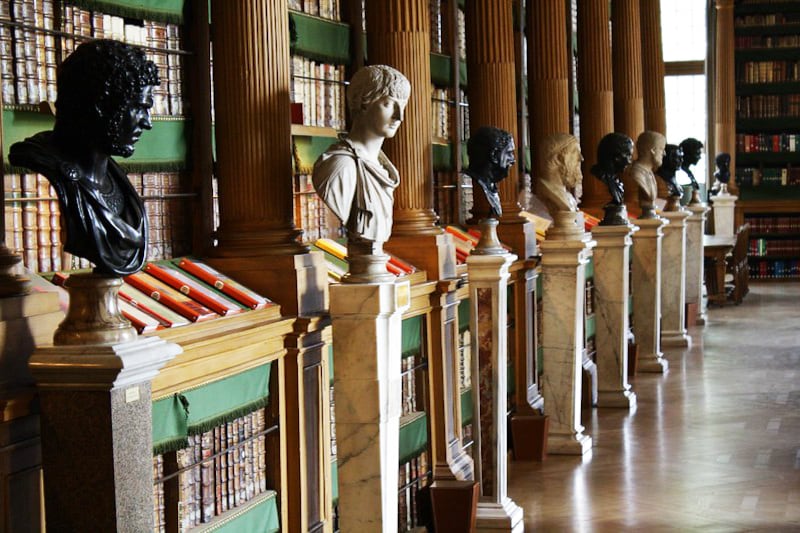

Sliding ladders lean against a balcony that encircles the reading room, which is lined with wooden Corinthian columns. Beneath the columns sit some 90 antique busts, including a terra cotta rendering of Benjamin Franklin crafted by Jean-Jacques Caffieri—the personal sculptor of Louis XV, who also designed the ornate metalwork on the Palais Royal’s grand staircase. Levecque even pointed out a small, hidden door that blends seamlessly into the stacks. Beyond it are offices and other parts of the library that only staff have access to.

The Bibliothèque Mazarine was founded in the mid-17th century by Jules Mazarin, the influential Franco-Italian cardinal and politician, who served as the prime minister of France. Widely rumored to have been the longtime lover of Louis XIII’s wife, Anne of Austria, Mazarin served as her closest advisor when she became regent following the death of her husband from tuberculosis in 1643, and was even tapped with educating her young son, King Louis XIV.

Along with his appreciation for books, the astoundingly wealthy cardinal also had a love of bling, amassing a remarkable collection of jewels. Among them are the famed collection of 18 diamonds—known as “the Mazarins”—that he bequeathed to Louis XIV. One of Mazarine’s giant gems hit the auction block at Christie’s a few years back. The 19-carat, pale pink diamond ended up selling for almost $14.5 million.

Originally located in his private mansion, Mararin’s library initially served as a repository for his extensive private book collection. The library began welcoming scholars in 1643 and opened to the general public nearly two decades later.

Mazarin fled France during the series of civil wars known as the Fronde, and his beloved library was auctioned off. When he returned to power in the mid-17th century he gradually restored the collection, but moved it to different quarters where it has remained ever since.

Today, the building is housed in the left wing of the Institut de France. Formerly the Collège des Quatre-Nations (a school that Mazarin also founded) the institute has served as the headquarters of five learned societies since the late-18th century, including the prestigious Académie Française. The Institut de France also manages museums and historical attractions throughout the country, including the Musée Jacquemart-André, the Château de Chantilly, and the Domaine de Chaalis.

The institute is situated on Quai de Conty near the banks of the Seine and its neoclassical dome can be seen from the adjacent Pont des Arts—the iconic wooden pedestrian bridge that links the building with the Louvre’s central square. Designed by Louis Le Vau, the Sun King’s favorite architect, the palace-like building merges elements of French Neoclassical architecture with Italian Baroque. Another neoclassical element was added in 1824 when the architect Antoine Vaudoyer built the grand staircase leading to the library.

In spite of its majestic high ceilings and rich collection of objet d’art, the Bibliothèque Mazarine is somewhat small compared to some of the city’s other libraries, which gives it an unexpectedly cozy vibe. It’s also a popular student haunt and is often filled with French scholars (and study abroad kids in the know) crouched over long, leather-covered tables and tapping away on laptops.

The warm ambiance is part Harry Potter film set, part regal study hall—the kind of place in which you would want to hunker down during a gloomy February afternoon and lose yourself in an obscure 18th-century volume on French literary history.

While the library keeps some 200,000 titles—many of them contributed by Mazarin himself—covering a wide range of subjects, its more modern collections focus on French history, particularly literary and religious history. The collection also includes books in foreign languages, including Italian and English.

Altogether, the library boasts some 600,000 documents, including numerous medieval manuscripts and an extensive collection of rare books. The oldest document, Levecque said, dates back to the ninth century. More than 200 artworks and antique furnishings round off the collection, including Madame de Pompadour’s above-mentioned chandeliers, which, upon closer inspection, are adorned with tiny cherubs.

The library’s most valuable treasures, however, aren’t on display. Among its holdings is one of the only existing copies of the Gutenberg Bible. Printed in 1455 by Johann Gutenberg, the book is the first in the West to have been printed from movable metal type. The bible is kept in a separate room under lock and key and is off-limits to everyone save for scholars. But not just any scholars, either.

“There needs to be a legitimate reason to see it, something pertaining to their area of expertise or academic focus,” Levecque explained.

“Can’t curious journalists have a look?” I pressed.

Alas, no.

While the bible and other rare documents may be hidden away, the library and its treasure trove of books and antiques are available to anyone who wants to enjoy them. Admission is free, and a pass (also free) valid for five consecutive days is available for out of town scholars or book-loving tourists who know that a single trip won’t suffice. For those lingering longer in the City of Light, an annual library card is available for €15 ($17.75)—cheaper than your typical coworking space and far easier on the eyes.

The library also holds several exhibitions every year, some of which feature its more valuable and lesser-known treasures and documents. Free guided tours for individuals and small groups are also available. The tours are in French, but Levecque said that tours with an English-speaking curator can usually be arranged in advance.

Even though the library’s collection has been digitized, its card catalogues were not done away with. Levecque said they function as a backup in the event of a technical glitch with the electronic system. The motivation for keeping the catalogues around may have been rooted in practicality, but the cabinets and their rows of slightly weathered looking cards within add to the atmosphere.

The reading room is equipped with wireless internet and 10 computer workstations, as well as 140 seats. But in this new era of social distancing, only a fraction of the chairs can be filled. Still, I was surprised to see as many people as I did in the room. Whether a bloody revolution or a global pandemic, nothing, it seems, will keep the library’s devoted regulars away.

“Bibliothèque Mazarine has always been a public library that is open to all,” Levecque said. “People come here from all walks of life. It’s very diverse.”

This diversity and willingness to welcome the public, she adds, is what sets the library apart from Paris’ other book rooms.

That and its striking, movie set-like interior, perhaps.

The library’s slender columns and leather-bound stacks are unlikely to grace the big screen any time soon, though. Levecque said that obtaining a permit to shoot here, is “prohibitively expensive,” adding that shootings would also temporarily close the library. A reminder that even though it may look camera-ready, more than three and a half centuries since its inception, Bibliothèque Mazarine remains true to its roots.

Besides, no film could ever convey the delectable smell of historic tomes.