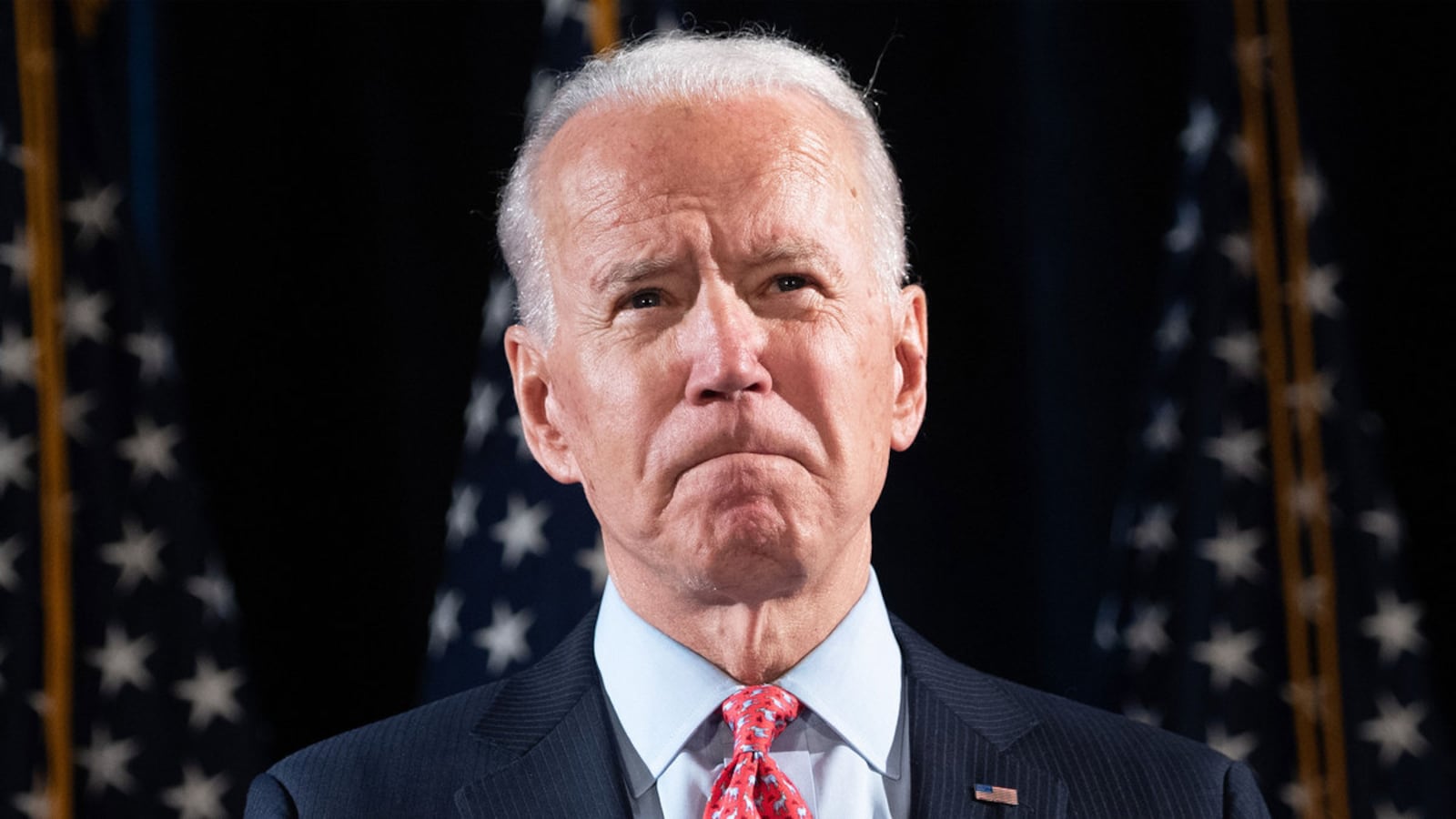

Appearing in an Instagram live chat with soccer star Megan Rapinoe on April 30, presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden made a spontaneous, vague statement about how he’s been “speaking to a lot of Republicans,” including “former colleagues, who are calling and saying ‘Joe, if you win, we’re gonna help.’”

Then he showed his hand: “Matter of fact, there’s some major Republicans who are already forming ‘Republicans for Biden,’” the former vice president said. “Major officeholders.”

The comment hardly received any attention at the time. But in declaring it, Biden ended up tipping off the earliest stages of a brewing effort that’s starting to get underway in certain Republican circles behind-the-scenes.

Interviews with several of the most prominent NeverTrump Republicans reveal that for now, the nascent effort is loosely defined and could ultimately take a variety of forms. But preliminary talks about messaging, engagement, leadership, and rollout are starting to be broadly sketched out, according to sources directly familiar with the matter. And the talks have happened more frequently as Biden moves solidly into general election mode.

“It is literally just forming,” one former top Republican Party official involved with the preliminary discussions told The Daily Beast. “I’ve had several conversations with people who have approached me. It’s going to take off, it’s going to happen. The question is to what degree and form it does,” the source, who was granted anonymity to speak candidly about private discussions, said.

“You don’t want something like this out on the street before it needs to be,” the GOP source added. “It just makes it much harder to do.”

The contours of a developing “Republicans for Biden” movement are indeed fluid, with longtime operatives and former party loyalists mixed on what a final product would look like and when it might come into fruition. The movement behind-the-scenes is in contrast to the very public effort to unite the left, but matches Biden’s own professed fondness for working with Republicans.

When presented with Biden’s comments, GOP sources interviewed referenced two main possibilities: an external group that would work on his behalf as a political action committee—similar to other Democratic-led outside groups—that could theoretically clear a pathway for others to join; or an internal operation within Biden’s campaign, with one or more recognizable Republican figures joining as the public face.

A second source well-placed in Republican circles—who has had conversations with senior Biden advisers in recent weeks—said that any mounting effort would most likely come from within the campaign’s vast network.

“My impression is the official one will be part of the campaign,” the Republican source said, referencing the apparent “Republicans for Biden” group Biden mentioned himself.

Among the GOP’s more ardent anti-Trump faction, several names came up in conversation when asked who could theoretically have a role in an outside political entity, which would not be allowed under campaign-finance laws to coordinate with the campaign directly. Those names include former Sen. Jeff Flake (R-AZ), Wisconsin-based political analyst Charlie Sykes, conservative media giant Bill Kristol, former Republican National Committee Chairman Michael Steele, longtime campaign operative Steve Schmidt, former Rep. David Jolly (R-FL), and columnist Mona Charen, among others.

Meanwhile, one name in particular has been floated as a choice to help give legs to such an effort from the inside: former Republican Ohio Gov. John Kasich. The source who has spoken to top Biden allies about a number of topics said there has been discussion in Bidenworld about Kasich, a leading NeverTrump voice, who joined as a CNN analyst after leaving office in January 2019.

A senior Kasich strategist denied any discussions.

“It’s done, but the reason it’s not common is there are few people willing to do that,” longtime Democratic campaign strategist Joe Trippi said about the possibility of a Republican joining a Democrat’s campaign in this capacity, or vice versa. “It’s not rare on the Biden campaign’s part. You just don’t usually have that many prominent people usually willing to cross lines in the middle of a presidential campaign.”

But when presented with both options, Trippi said the campaign would most likely want outside and internal GOP help if available. “If you’re the Biden campaign, you want both those things to happen,” he said. “I don’t think it’s either or.”

Reached for comment, a spokesperson for the Biden campaign said, in part, “Vice President Biden is running for president to unite our country and rebuild the soul of the nation, and to accomplish that we need to bring together Americans from across the political spectrum to build the broadest possible coalition to defeat Donald Trump.”

“As we move into the general election, we're going to continue to ramp up our outreach to Americans of all political stripes—including the many disaffected Republicans who are horrified by Trump’s historic mismanagement of the coronavirus crisis.” The campaign declined to elaborate on Biden’s own prior statement about a “Republicans for Biden” group forming.

Since securing near-instant party unity following his sweeping victory in South Carolina, Biden’s campaign has been focused on weaving the values of progressive leaders into their emerging platform. After Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), his final primary opponent and longtime Senate friend, departed from the race and endorsed him last month, the former rivals announced the formation of several task forces as a way to prioritize progressive issues.

“My impression, more than an impression, is they have been cautious about going ahead with anything official ‘Republicans for Biden,’ [partly because] they want to make sure the Democrats are all OK first,” said the source who has been in talks with Biden advisers.

Still, Biden has already been sending less-than-subtle signals to Republicans on his own.

Throughout much of the primary, the former VP remained the national frontrunner with the explicit message that he can appeal to a broad coalition of individuals needed to beat Trump, often maintaining more moderate policy positions when his opponents tilted leftward. At one juncture in late 2019, he even floated the possibility of selecting a Republican running mate, an idea he has since backed away from since becoming the party’s presumptive nominee.

As his campaign continues to plow forward toward November, Biden has taken new steps to appeal to Republicans. In late April, he said during a virtual fundraiser that he would consider naming Republicans to his Cabinet under the stipulation that they were “the best qualified person.”

To some Republicans, that type of public messaging from Biden, paired with early private discussions, is setting the right groundwork for one or more efforts to take off in earnest on his behalf, albeit at a slower pace in the age of COVID-19.

“I know that it’s happening and it’s coming together,” Jennifer Horn, a longtime Republican operative and former state party official, told The Daily Beast. Horn said she was approached several months ago by a national GOP operative about specifically joining a “Republicans for Biden” effort, but hasn’t been involved directly. Instead, she’s focused her attention on the Lincoln Project, an anti-Trump super PAC she advises along with George Conway, the husband of White House adviser Kellyanne Conway, Schmidt, and political operatives John Weaver and Rick Wilson (a Daily Beast columnist).

With less than six months until Election Day, there are already a number of Republicans and ex-Republicans who have stated they intend to vote for Biden. On Tuesday, former CEO of Hewlett-Packard Carly Fiorina, who competed against Trump in 2016, declared that she “cannot vote for Donald Trump in 2020,” while entertaining the possibility of not voting.

For Republicans aiming to get a pro-Biden movement off the ground, that potential scenario—where voters may feel they simply can’t vote for Trump or Biden—is a nightmarish thought.

“It’s really hard to get people to take that last step,” Horn said. “To publicly say and do something. You need five or 10 people who are all ready to go at the same time.”

There’s also a mounting concern in at least some corners, according to the GOP source who has been in conversations with other Republicans about the possible difficulties, that Biden’s campaign might not be able to join forces in a seamless way, noting technical and operational difficulties they have had recently.

“A coalition like this has to be knitted together very carefully because it can very quickly fall apart and everyone is made to look stupid,” the source said. “That’s the last thing that anyone who gets out on this bandwagon wants to do when they realize that the wheels aren’t on securely.”

While most Republicans interviewed spoke candidly about the first portion of Biden’s statement, when asked about the second part—that “major officeholders” are starting this effort—no GOP source contacted could present a concrete name. Indeed, most admitted they would be shocked to hear of anyone at the Senate or House level likely to take such a step, but did not rule out the possibility that Biden could be referring to state or local elected officials.

Others are less convinced. Former Rep. Joe Walsh (R-IL), who plans to vote for the Democrat in an expected Trump vs. Biden matchup, said “it’s still a leap,” for a Republican to publicly say they’re against Trump. “It still takes some balls, and so I don’t think you’ll see a huge number of well-known names,” he said.

“I don’t think there’s any freaking way a current elected Republican would ever sign their name on to Republicans for Biden,” Walsh said. “They’ve demonstrated over the course of the last three years that they’re just too damn cowardly to do that.”

That sense of skepticism was picked up in other conversations.

“No one wants to end up like Jeff Flake,” Fergus Cullen, a Trump critic and past chairman of the New Hampshire Republican Party, said about the former Arizona senator, who retired with an isolated anti-Trump crusade early last year.

The sense of resignation shared among some disgruntled Republicans is built, at least partially, on recent history. Early in the presidential cycle, so-called NeverTrump Republicans were not able to woo a single marquee challenger into primarying the president, with Kasich and others passing on the opportunity.

Former South Carolina Gov. Mark Sanford ran in the GOP primary for a short time before abandoning his run in November, leaving Walsh and former Massachusetts Gov. Bill Weld as the most prominent remaining options. Both failed to gain much traction or sway any prominent current GOP office holders to their cause.

“This is about killing the alligator closest to the boat,” said Rick Tyler, who served as Sen. Ted Cruz’s (R-TX) communications director during his 2016 presidential campaign. “People say how can you support Biden? The alligator that’s going to kill us is the closest one, and that’s Trump,” he said.

“I don’t want Biden to be president. I don’t want Trump to be president,” he added. “Am I willing to have Biden be president so Trump won’t be president? You’re damn right I am.”