On the mournful anniversary of the blatant murder of George Floyd, an inconvenient truth confronts American politics: Violent crime has shot up dramatically in cities over the past year, amid the pandemic, yes, but also amid a wave of policing protests and radical reforms.

Luckily, after a year where the number of shooting victims in New York City doubled, there is a leader who supports commonsense criminal justice reform and yet has a record of speaking plainly about “predators on our streets” and the need to remove them while also dealing with root causes: “It doesn’t matter whether or not they’re the victims of society. The end result is they’re about to knock my mother on the head with a lead pipe, shoot my sister, beat up my wife, take on my sons.”

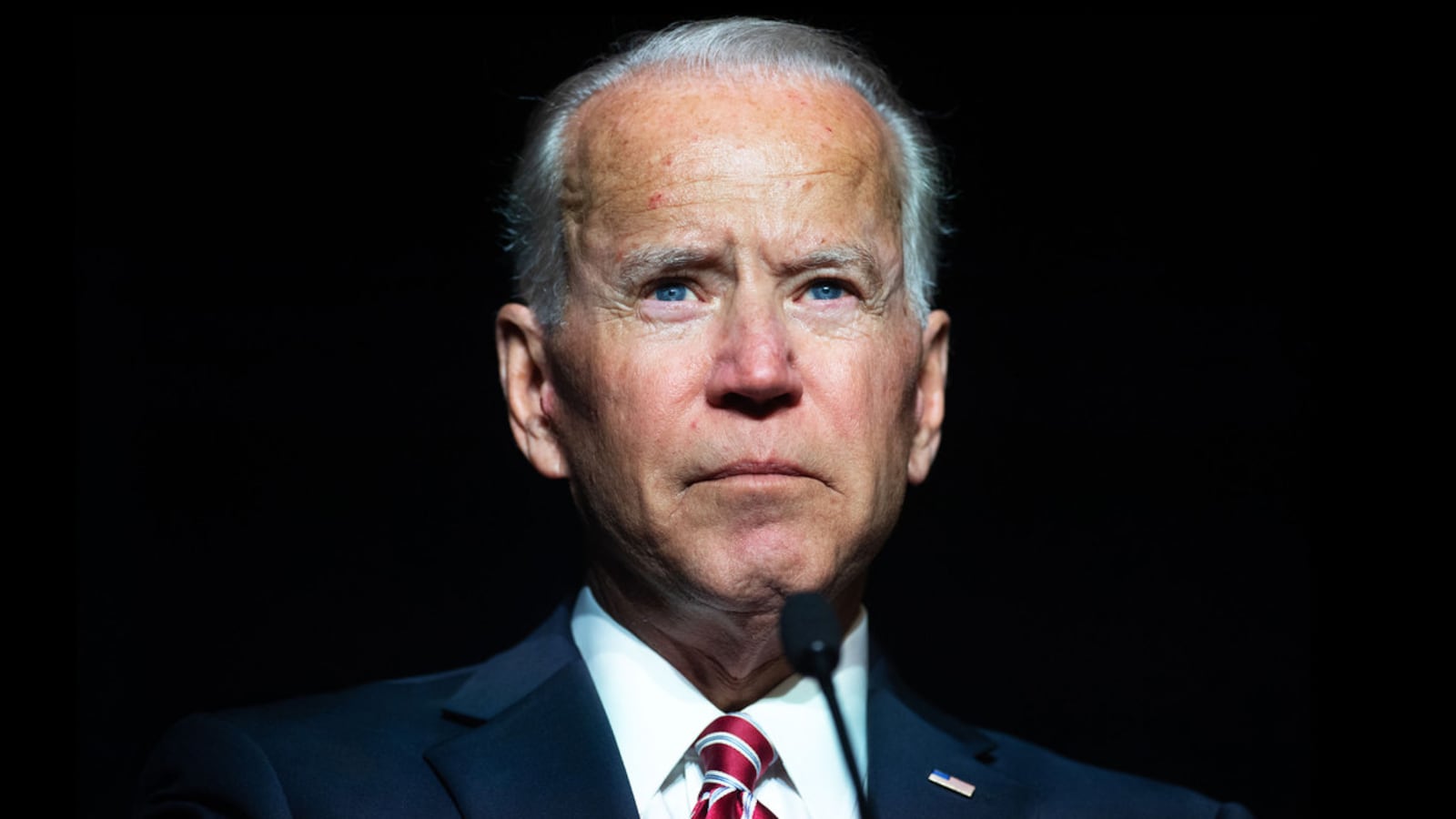

Or, rather, there was a leader who knew how to talk about getting violent crime under control. To confront what threatens to be an emerging crime epidemic, the kinder, gentler Joe Biden of 2021 might want to recall and channel some of the Joe Biden of 1993, who understood the personal real-world danger of out-of-control crime and the political danger of being tagged as a “soft-on-crime” Democrat.

First, though, some context is in order. Between the early 1960s and the 1980s, the crime rate doubled, peaking around 1991. It continued to fall for two decades after the passage of the 1994 crime bill, sometimes called the Biden bill, before the violent crime rate began slowly rising around 2015—mostly in a few big cities.

Last year, it exploded. As The New York Times’ Ezra Klein recently noted, “Early estimates find that in 2020, homicides in the United States increased somewhere between 25 percent and nearly 40 percent, the largest spike since 1960, when formal crime statistics began to be collected. And early estimates indicate that the increase has carried over to 2021.”

As is the case with inflation (transitory!) and the border surge (cyclical!), Biden is hoping “it will disappear” (in the words of his predecessor).

And maybe it will. After all, the COVID-19 pandemic is the most obvious driver of the 2020 spike. People are more stressed and more idle, and many of the mediating institutions—community groups, schools, churches, and other anti-violence organizations—were mostly shuttered.

If the crime rate recedes in 2021, the spike will be attributed to the pandemic, as well as to the killing of George Floyd, which kicked off a growing distrust between communities of color and the police.

But what if it does not recede or keeps rising?

The problem for Democrats is that Biden would be caught holding the bag, and the rise in crime would reaffirm long-held stereotypes about bleeding-heart liberalism. As was the case in the 1960s and ’70s, it would be perceived as a result of progressive policies, including (this time around) the decriminalization of marijuana, criminal justice reform policies that end “mass incarceration,” the rise of “mostly peaceful” protests, and the proliferation of homeless “tent cities” in America’s urban areas. The backdrop would be a liberal media that says violent protests are good and lodges a defense of looting. The message will be that we got soft and repeated the mistakes of the past.

While there may be some truth to this, multiple factors probably contributed to the decline in crime in the early 1990s (some people even argue 1973’s Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion, was the biggest factor). But the simplest explanation, and thus the most politically potent, is that aggressive police tactics put more cops on the streets who took more criminals off of them—until we (here, I’m even including Biden) started moving away from these policies just in time for a spike in violent crime.

Never mind that crime rates were already falling before Biden even authored the 1994 crime bill—and before Rudy Giuliani became mayor of New York City (a city where crime is currently one of the top priorities of Democratic voters) and implemented his “broken windows” theory of policing. Fear of crime has all sorts of externalities that progressives may not like, including (ironically) a rise in gun sales and a turn toward “law and order” politicians.

Ezra Klein goes on to say, “In the 1970s and ’80s, the politics of crime drove the rise of mass incarceration and warrior policing, the political careers of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, the abandonment of inner cities. If these numbers keep rising, they could end any chance we have of building a new approach to safety, and possibly carry Donald Trump—or someone like him—back to the presidency in 2024.”

Trump, of course, made “American carnage” a theme of his inaugural address. That was in a year when there were 17,250 murders in America, according to the FBI. Preliminary data for 2020 shows more than 20,000 murders—a number the nation last hit in 1995.

If Biden and the Democrats (who run most major cities) are going to stem this tide, they simply cannot allow a narrative to take hold that they let their guard down. This doesn’t mean ditching all of the “commonsense” criminal justice reforms, such as ending mandatory minimum sentences, ending qualified immunity, and putting an end to police neck restraints, but it does mean re-committing to a style of politics that cares more about the victims and regular Americans than it does about coddling criminals. It means recognizing the (real and perceived) threat that a weak-on-crime image poses to the Democratic party—possibly for a generation.

Words matter, and just as candidate Biden’s calming rhetoric was needed to contrast with Trump’s harsh words, President Biden may have to once again reinvent himself to deal with this new existential challenge. In a 1994 Senate floor speech, Biden observed that, “Every time Richard Nixon, when he was running in 1972, would say, ‘Law and order,’ [and] the Democratic match or response was, ‘Law and order with justice’—whatever that meant. And I would say, ‘Lock the S.O.B.s up.’”

We may be nearing a time when Biden is once again uniquely suited to speak to a new, emerging problem—but with a twist. Biden should acknowledge that his 1990s law-and-order rhetoric painted with too broad a brush, while reaffirming that his basic premise (that dangerous people belong in jail) was always correct. This new perspective (informed by the wisdom and experience), might sound something like this: “Lock up the S.O.B.s—just not their friends and cousins who happen to be hanging around.”

If this still sounds too harsh, consider the alternative: handing back power to the next Trump (or Nixon), whose mantra will surely be, “Lock them all up and let God sort ‘em out.”

Biden will also have to continue to vigorously “police” the left and push back on the defund rhetoric that became all too prevalent and mainstream in the last year, even as moderate Democrats warned it would have negative consequences in the 2020 elections.

It won’t be easy. This isn’t Biden’s only challenge. A trifecta of tribulations threatens to test his grand ambitions. Incipient problems like inflation and a growing border crisis loom on the horizon. But the rise of violent crime may be the jewel of this unholy trinity.

If he hopes to become a transformational president, or even a moderately successful one, this is one more metaphorical bullet Biden will have to dodge. If the era of big government is to return, then the era of violent crime can’t.