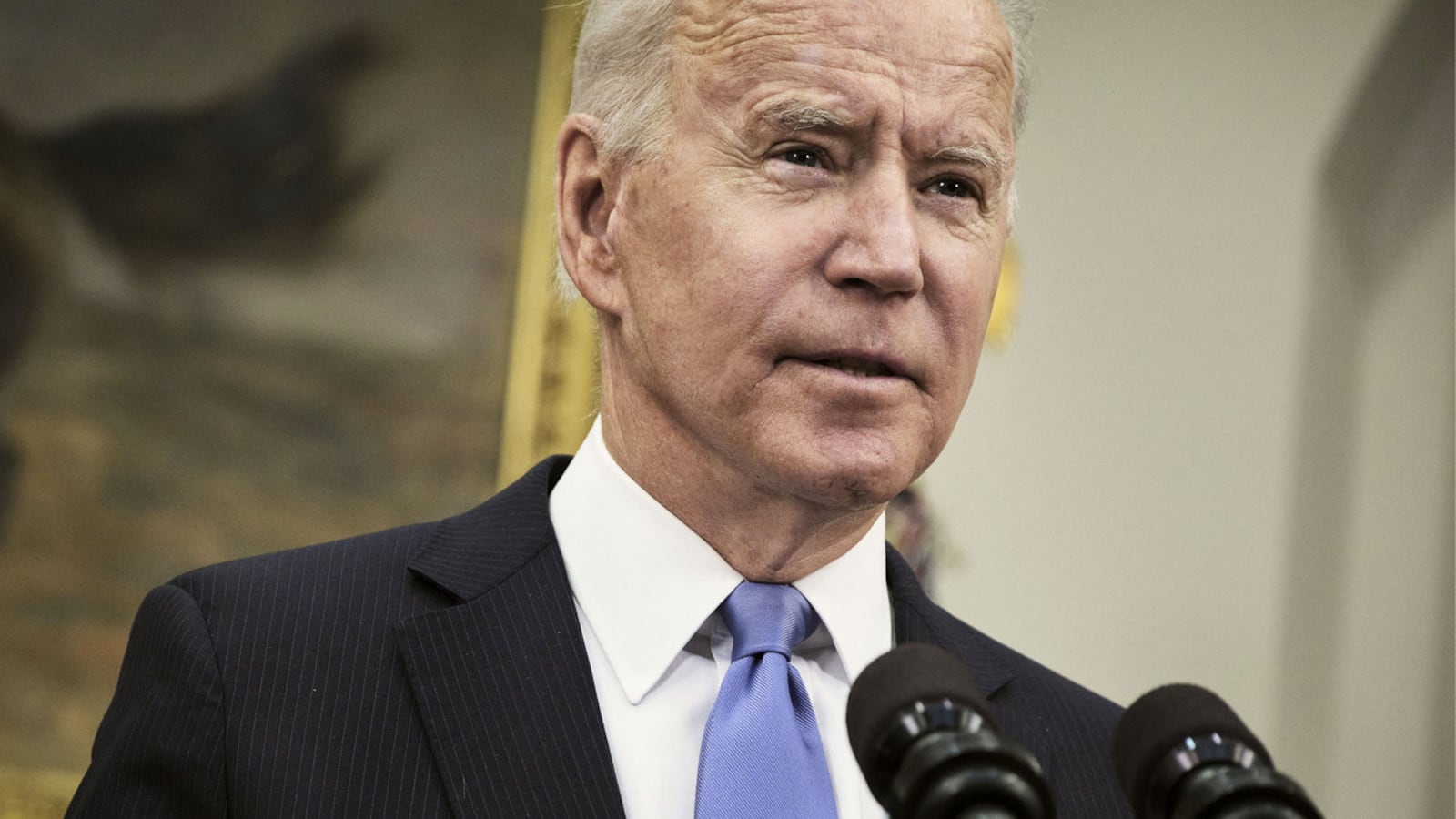

The Republican Party remains as dedicated to owning the libs as they were during the Trump administration, but President Joe Biden still seems to think that passage of a massive, bipartisan infrastructure deal is right around the corner.

The GOP that Biden knew during his 36 years in the Senate—even the GOP Biden worked with during his eight years as vice president—has, of course, changed. Moderate senators like Bob Corker (R-TN), Richard Lugar (R-IN), and Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-TX) have been replaced with a conference full of naked partisans like Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), Mike Braun (R-IN), and Ted Cruz (R-TX). And yet, the White House continues to say Biden is “eager to engage” with Republicans and potentially strike a bargain on infrastructure.

Even Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), who has made major deals with Biden in the past—at least, when those deals suited McConnell—seems to have little interest in actually achieving a compromise on infrastructure. At the beginning of this month, McConnell publicly said “100 percent” of the GOP’s focus was on “stopping this new administration.”

During a weekly Senate GOP leadership press conference on Tuesday, in a sign of how far apart the two sides are, McConnell suggested he’d like to see the administration “repurpose” some of the money Democrats allocated for state and local funding in their COVID relief bill toward infrastructure—a red line for Democrats. And the No. 2 Senate Republican, John Thune of South Dakota, said he thought Republicans and Democrats were making progress on an infrastructure bill until GOP senators met with Biden at the White House last Friday.

“Friday clearly was a setback,” Thune said. “My impression is the staff at the White House isn’t as inclined to make a deal as the president is.”

Republicans are keenly aware that Biden wants a deal. A senior GOP aide told The Daily Beast on Tuesday that there was a “legitimate desire” among Republicans for an infrastructure package, but said that Democrats were making it “impossible with all of their extraneous demands.”

“We want a deal,” this aide said. “But we also have no doubt that Biden would love a deal, so he needs to come our direction.”

Biden’s zeal to strike a bipartisan agreement is looking increasingly like a weakness, just as it was during the 2012 fiscal cliff negotiations when Biden locked in the expiring George W. Bush tax cuts in exchange for Republicans keeping the government running.

In the near-decade since Biden brokered that deal with McConnell, the GOP has tilted even further toward extremism and obstruction. There’s much less to be gained by working with Democrats than by blaming them, and Donald Trump’s politics of grievance has taught Republicans that their voters will reward dysfunction and chaos over order and legislative achievement.

The differing political and governing goals have left the two parties not just speaking past each other, but speaking different languages. For Biden, though, it might as well be a different millennium.

Biden has already come down from an initial offer of about $2.3 trillion for infrastructure, suggesting to GOP senators on Friday that Democrats could do a $1.7 trillion bill by trying to do separate legislation for manufacturing and cutting some funding for roads, bridges, and broadband.

Republicans initially countered with a $50 billion increase to their roughly $550 billion plan, a move that White House press secretary Jen Psaki suggested was inadequate.

“Our concessions went 10 times as far as theirs,” Psaki said on Monday. “So the ball is in their court.”

Speaking with reporters on Tuesday, Psaki said the president expects this latest round of negotiations to reflect “a week of progress.” And she described Biden’s counterproposal cutting nearly half a trillion dollars from the infrastructure plan as a “good faith effort” that should be met in kind.

“The president’s only line in the sand is inaction,” Psaki said, adding that the president was “encouraged” by Republicans working on a counterproposal—even one that leaves intact Trump’s tax cuts that were largely aimed at the wealthy.

“If they don’t want to touch the 2017 tax cuts, a $2 trillion tax cut that did not end up having a windfall back to the American public, that’s their decision,” she said.

There does appear to be some movement on the Republican side. Sen. Roger Wicker (R-MS) said a group of GOP senators would present a nearly $1 trillion plan, led by Sen. Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia, to the White House on Thursday. And Republicans are apparently drafting a backup offer if negotiations with the White House fall apart.

But there’s still a nearly $1 trillion gap—and that’s just the fiscal disagreements.

Biden’s infrastructure plan would pay for itself over a 15-year span by raising taxes on corporations, the wealthy, and on certain capital gains, as well as by rolling back the Trump-era tax cuts. Financing for the Republican plans, would be heavily dependent on user fees, tying the gas tax to inflation, and rolling over unused stimulus funds from previous COVID-19 relief packages.

While both Biden and the Capito plans advocate for strengthening IRS enforcement in order to better catch tax cheats and increase revenue, Republicans have balked at the $85 billion in increased funding for the agency that Biden says is needed to do it. And that’s to say nothing of the differences between the proposals on things like childcare, elder care, housing, research and development, and workforce development.

Democrats have a slim majority, but that does them little good in this particular negotiation where the rules dictate that they need 60 votes to move anything closer to Biden’s desk.

Democratic leaders are, however, already gaming out options that presuppose universal Republican opposition—and looking for ways to attract moderate Democrats, who may have shopping lists of their own.

One potential mechanism leaders are exploring to attract fence-sitters is adding military infrastructure spending priorities to the plan. Although Biden’s pitch on his American Jobs Plan is largely couched in rhetoric about increasing the nation’s economic competitiveness, funding for revamping military infrastructure could be framed as increasing military competitiveness, as well.

“Nearly $4 billion in [Department of Defense] construction funding was redirected to ‘build’ the border wall,” one Democratic staffer on the House Appropriations Committee told The Daily Beast. “If you’re a conservative Democrat with a joint base in your district, you’d be more than happy for some of that money to be redirected away from the wall and towards a huge local employer.”

According to two sources familiar with the thinking, Democrats see adding funds for the Department of Defense’s child development program, in particular, as a way to corral Democrats across the political spectrum too.

“If you have a joint base in your district that employs 20,000 people, you’re gonna welcome that money,” the staffer told The Daily Beast.

Democratic lawmakers have thus far tolerated Biden’s appeal to bipartisanship, assuming that there’s no harm in allowing the president to try and reach a deal with Republicans, especially if it means they could potentially deliver more legislatively. But their patience does appear to be wearing thin.

"I understand that the President wants to make clear that Democrats are willing to engage in good-faith bipartisan negotiations,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) told The Daily Beast on Tuesday. “But the clock is running. We need to get an infrastructure bill through. And we need to get it through now.”

Warren said Republicans had already repeatedly indicated they were not interested in an infrastructure package that is “big enough to meet the need,” and she said they'd already eliminated “entire categories of help, like child care, which profoundly affects women's ability to get back into the workforce."

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) told Politico recently that he didn’t see the negotiations going anywhere.

“We’re too far apart,” Whitehouse said. “Because I think Mitch’s ultimate purpose is not compromise but delay and mischief.”

Whitehouse added that Biden was “entitled to his judgment” on the negotiations, “but if I were in a room with him, I’d say it’s time to move on.”

And many Republicans sound just as fatalistic. Sen. John Barrasso (R-WY)—the Senate Republican conference chair—told reporters on Tuesday that the two sides were “very far apart.”

He couched that by saying, if Biden wanted to narrow the scope of his bill to just what Republicans believe infrastructure is—like roads, bridges, and tunnels—there was a possibility. But if Biden wanted a plan that would cost trillions and raise taxes, “then he is going to find no Republican support.”

Still, some Democrats have embraced Biden’s search for a bipartisan deal as part of the president’s process.

After all, Biden’s calls for bipartisanship were useful during COVID relief negotiations, even if they were largely performative. Although there wasn’t a single Republican in the House or Senate who voted for the $1.9 trillion COVID package, more than 40 percent of Republicans supported the bill, giving the legislation at least an air of bipartisanship. So with Biden once again pleading for a deal, it could be politically useful for him to exhaust all options with Republicans before turning to the partisan reconciliation process.

"I don't think there's any harm,” Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI) told The Daily Beast. “I just think we have to be clear-eyed about where we stand, which is more than $1 trillion apart.”

Schatz added that he was “serene” about Biden trying to find a deal with Republicans. “If there's a breakthrough, great, if not, we should just move on,” he said.

—with reporting from Sam Brodey.