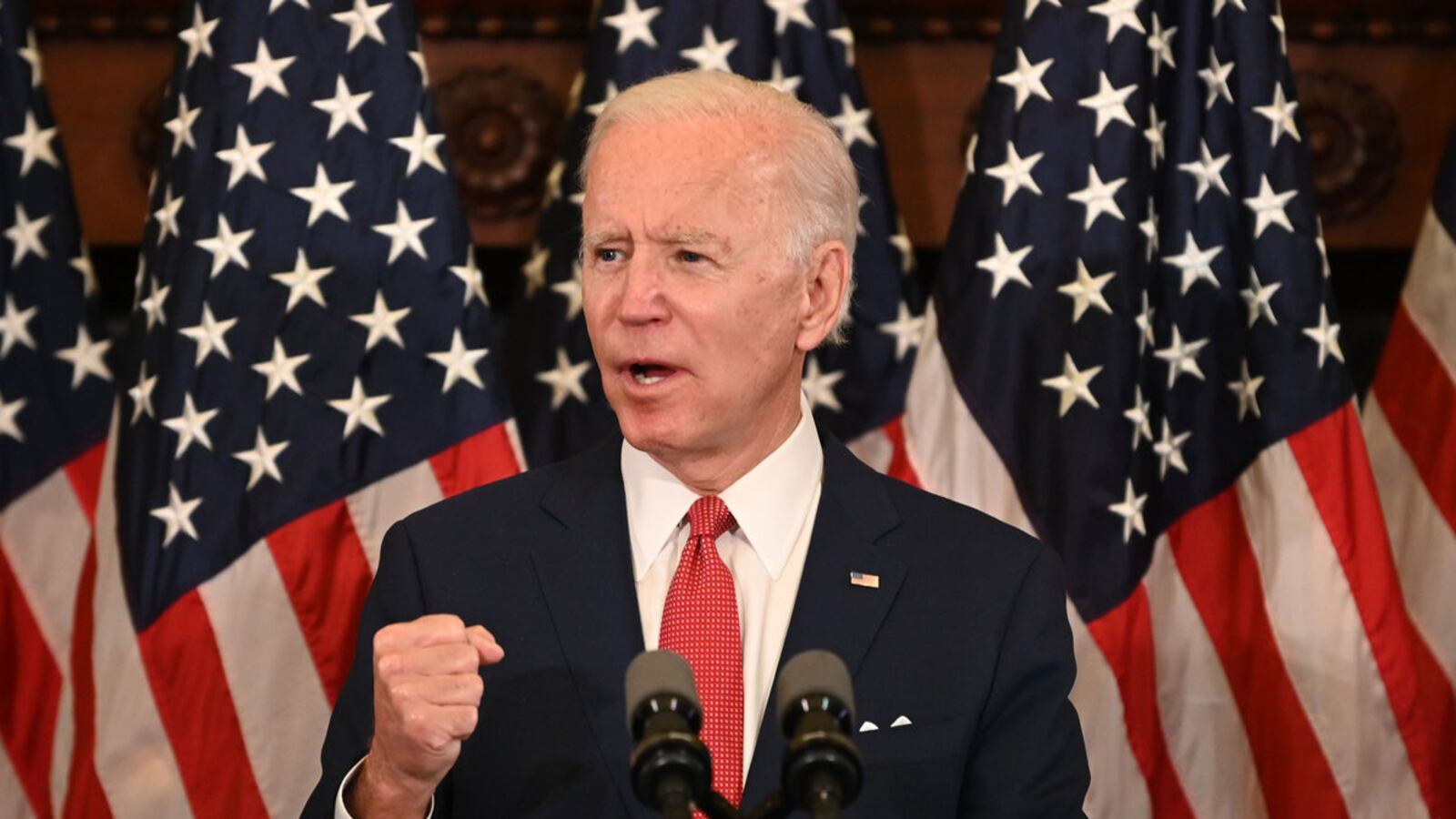

One of Joe Biden’s big campaign promises was to restore norms and institutions in our country. In other words, he would not be Donald Trump.

And while the nation’s political tone has calmed, the Party of Biden is gaslighting us in an entirely different way: by redefining what had been the meaning of widely understood words and terms to suit their political interests.

Twisting language isn’t a new thing. But in modern American politics, this usually manifests as hyperbole (like Biden’s suggestion that the Georgia election law is worse than Jim Crow), euphemisms like “downsizing,” politically correct neologisms like “Latinx,” or issues framed to highlight your strengths (or your adversary’s weaknesses). The technical term for this type of wordplay is “bullshit,” but in polite company it’s called “spin.” And whether you’re a disciple of Frank Luntz or George Lakoff, it is an accepted and bipartisan facet of the game of politics.

When Republicans talk about a death tax instead of the inheritance tax, partial-birth abortion instead of late-term abortion, or the incredibly lame Democrat Party instead of Democratic Party, they are attempting to put a thumb on the scale and change our perceptions. Ditto when big-government progressives talk about “investment” before they raise your taxes. Again, this spin is bipartisan. But here’s the thing: They are not pretending these words and terms mean something entirely different from how they are commonly defined.

What Democrats are doing today, however, is much more egregious and pernicious. They are not just spinning or framing issues; they are redefining generally accepted terms.

Let’s take, for example, the term “infrastructure,” which most of us understand to mean things like bridges, roads, airports, and subways. In a recent speech, Biden acknowledged the shifting definition, saying, “The idea of infrastructure has always evolved to meet the aspirations of the American people and their needs, and it’s evolving again today… It still depends on roads and bridges, ports and airports, rail and mass transit, but it also depends on having reliable, high-speed internet in every home. Because today’s high-speed internet is infrastructure.”

This seems like a reasonable, if modern, interpretation, but the bill that Democrats are selling as infrastructure also contains $400 billion for long-term care. Now, if you want to get super esoteric, you could argue that everything is infrastructure. Just as you can’t go to work without roads, how are you going to work if your aged parent needs home care that you can’t afford? Then again, you could just as easily apply that to children. Indeed, Democratic Senator Kirsten Gillibrand recently argued that “Paid leave is infrastructure,” “Child care is infrastructure,” and “Caregiving is infrastructure.” But if you do that, then words mean everything, which is to say they cease to mean anything. By taking a popular issue and broadening its brand to be all-inclusive, Democrats hope to pass legislation authorizing hundreds of billions of dollars for unrelated parts of the progressive agenda.

Redefining words has the potential to not just win a given political argument but also (and more importantly) to undermine our ability to even communicate—to, in the words of the Bible, “confuse their language so they will not understand each other.” Recently, Barack Obama said, “If we do not have the capacity to distinguish what’s true from what’s false, then by definition the marketplace of ideas doesn’t work. And by definition our democracy doesn’t work. We are entering into an epistemological crisis.” Obama was, no doubt, thinking of Trump gaslighting us and right-wing “fake news” that spreads on social media, but the quote also applies to the Democratic Party’s current fixation with Newspeak. If you can simply redefine what a widely accepted word or term means, then it’s difficult for the marketplace of ideas, let alone democracy, to work.

Another example is the word bipartisan, which—in the context of policy debates—means winning votes from both Republican and Democratic members of Congress. But get a load of the slick sleight of hand Team Biden uses: “If you looked up ‘bipartisan’ in the dictionary, I think it would say support from Republicans and Democrats,” Anita Dunn, a senior Biden adviser, told The Washington Post. “It doesn’t say the Republicans have to be in Congress.” But as the Post’s Peter Stevenson pointed out, “...that’s a pretty different definition of ‘bipartisanship’ than the one Washington has been accustomed to for a long time—and it’s not how Biden defined it while campaigning for president last year.” (If you’re keeping score, Democrats are trying to pass their redefined definition of “infrastructure” by citing its “bipartisan” support—a term they also redefined.)

Democrats are also trying to redefine the term ‘court packing’. Everyone knows this term because FDR tried to do it in 1937; for example, in a 2017 NPR review of historian Robert Dallek’s Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Political Life, Ron Elving referred to “what many consider FDR’s greatest mistake, his 1937 ‘court packing’ scheme to add six seats to the U.S. Supreme Court.” Biden even once referred to it as a “boneheaded” idea (more recently, he appointed a bipartisan commission to study the idea). Some prominent Democrats are arguing for their new definition. “Some people will say we’re packing the court. We’re not packing. We’re unpacking,” House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerry Nadler said. He’s not alone. “Republicans packed the court when Mitch McConnell held Merrick Garland’s seat open nearly a year before an election, then confirmed Amy Coney Barrett days before the next election,” Rep. Mondaire Jones said.

To be sure, words and terms evolve organically over time. Thanks in part to people (like Biden) who frequently misuse the word “literally,” it is sometimes acceptably used to mean its opposite, “figuratively.” Words like “penultimate” and “nonplussed” are likewise so often misused that, at some point, they mean what people think they mean. Heck, the same is true for political terms like “liberal” and “conservative.” The difference here, though, is that this change is happening organically.

What Democrats are doing with language is the intentional inversion of customary meaning. In my book, that’s propaganda. That’s not what Americans were hoping for when they voted for Biden. That’s not a return to normalcy. That’s not a change we can believe in.