The currency of electoral politics is engagement. But what if engaging certain audiences is not always a good thing?

That’s the question the Biden campaign is trying to answer as it navigates a novel political landscape, in which the act of campaigning has been reduced to a series of decisions about which platforms to engage from the candidate’s home.

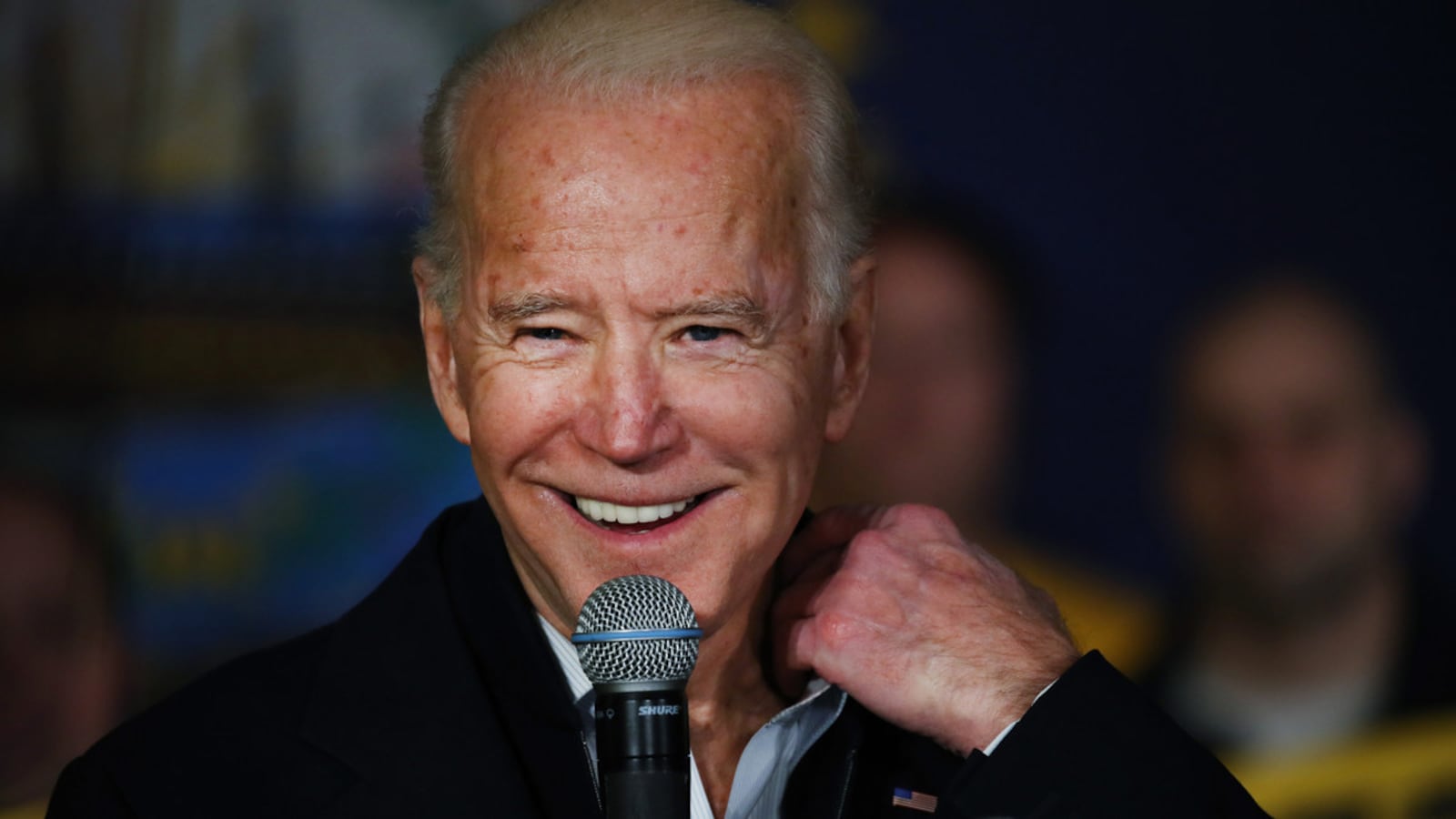

Often, the choices they’ve made have proved correct. Biden is, after all, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee with persistent, healthy polling leads over an incumbent president. But occasionally they have not, as evidenced by the storm kicked up Friday when, appearing on Charlamagne tha God’s The Breakfast Club, the former vice president said (in jest, the campaign insists) that one can’t be black and vote for Donald Trump.

The inability to get the balance just right remains an internal campaign riddle, one that has profound implications for November. For Biden, can less truly, actually, be more?

In an interview with The Daily Beast the day prior to the Charlamagne interview, Biden’s digital director, Rob Flaherty, didn’t directly say the campaign is deliberately limiting exposure. But he did say that the campaign wasn’t just cognizant of the dangers of over-engagement but actively strategizing against it. As documented by Peter Hamby in Vanity Fair, Biden’s appearances have been selected with the awareness that contrived settings are likely counterproductive—convincing the very audiences they’re trying to reach that he was there merely to shill for their votes.

“For us to try and force it by having him go on TikTok and Hit The Woah or whatever, that just doesn't compute with who the guy is,” said Flaherty. “And so, for us, it's... how do we use these digital tools in ways that aren't going to feel super weird for him to do?”

And yet, Biden’s appearance on The Breakfast Club shows the potential limitations that come with the approach. Placing your candidate on platforms that feel natural or accentuate his strengths makes a lot of sense, except perhaps when he eventually ventures beyond that bubble.

“For most candidates, more exposure is a good thing, but then there’s Biden,” said Rebecca Katz, a progressive strategist who has been critical of Biden. “It’s important to meet voters where they are, but only if you’re not offending them when you do it.”

Biden’s relationship with the internet has not always been quite so delicate. The depiction of him during the Obama years wasn’t flattering. But even the caricature driven home by countless Onion articles and accompanying memes was inherently relatable. He was the vice president who lacked self-awareness and said things that made his boss cringe. But he was also the aviators-wearing, scarf-discarding, DGAF uncle who drove the dope car and seemed fun to throw a few beers back with even though, in real life, he didn’t drink.

Being a presidential candidate, however, is different than being the vice president. And Biden’s experiences online during the 2020 cycle have not been all that enjoyable. During the primary, he lagged in building up a small-dollar donor network, despite benefiting from the Obama-Biden email list. His campaign’s engagement on social media platforms was pedestrian and he kept largely within his media comfort zone.

There was mockery that ensued on Twitter, as if the platform had another tone. But that proved to be just a small corner of the Democratic electorate. Biden made a bet that nostalgia for the Obama years and old-school campaigning would prove more determinative and, well, he was right.

Whatever plans the campaign had to adjust its approach online came to a halt with the spread of the coronavirus. Early on, it appeared that being confined to his basement merely accentuated Biden’s deficits. The portrait of a candidate stuck in the dial-up generation was hardened by the daily tech problems and the verbal stumbles that defined his live streaming.

And yet, once more, the mockery seems to have been overstated. Biden’s standing against Trump is both remarkably persistent and historically good for a challenger facing an incumbent. His grassroots fundraising has notably improved, having scored the single-day and single-hour record for donations through the online giving site ActBlue, according to ActBlue. And those who work in Democratic politics are slowly coming around to the possibility that maybe, just maybe, Biden’s team knows what it's doing.

“Contrary to what folks are saying in New York Times op-eds, I believe they're doing everything they need to be doing,” said Tim Lim, a longtime Dem digital strategist. “This pandemic makes all previous playbooks less relevant, so they should stick to what is working for the vice president and his campaign, and not spin their wheels just for the sake of doing so. And if you look at the polls and their fundraising, it seems to be working.”

When Biden was first on the presidential ballot 12 years ago, he didn’t have to worry about any of this. Not because the internet was still in its infant stages (at least politically) but because the man on top of the ticket—Barack Obama—had the type of charisma and message that translated across platforms. That stayed true for the eight years the two were in the White House. Obama experimented with different online mediums, held court with internet celebrities, and did shows like Between Two Ferns that would be dangerous territory for most politicians.

Biden is adopting a different tack. One of the principles of his online outreach is that the candidate himself can’t always be the primary messenger. That’s a reflection not just of how different he is from Obama but how the internet itself has changed. Peer-to-peer communication and trusted social networks are increasingly important, not just for grabbing eyeballs but for essential campaign functions like raising money, fighting disinformation, organizing political actions.

“People are looking for realness in an internet that they don’t trust,” is how Flaherty put it. “Their friends matter more. Trusted voices matter a little bit more. The internet has just gotten smaller in that way.”

In order to tap into that paradigm, the campaign has tried to create organic content that Biden-supportive voters or trusted voices can help push through various channels. But in order for that content to be successful, they’ve concluded, it can’t merely be anti-Trump. The prospect of getting the current president out of office may be a great motivator for the Democratic base. But the campaign’s own metrics show that people clicking on ads or videos that emphasize Biden’s positive qualities tend to give more money and have longer engagements.

As Biden himself said of his approach during a fundraiser on Friday night: “I think we can win online by connecting people, not tearing them apart, by showing compassion, not cruelty, by building a strategy that respects the campaign we’re running.”

What’s been notable for the Biden team is not just that the pro-Biden content has worked conceptually, but that it’s worked in ways that go against the tides of fairly recent conventional wisdom. In the age of short, home-made videos and viral memes, the campaign’s defining digital successes have been relatively lengthy videos that are expertly produced.

Straight-to-camera explainers from policy experts have gotten millions of views. Candid moments captured and re-packaged by campaign videographers have gone viral. A six-minute-long Biden riff on the Iran missile crisis that he gave at a campaign town hall became the campaign’s second-best-performing Facebook video of all time. More recently, sharply edited clips of Trump’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic have ricocheted across the internet.

Flaherty’s explanation for this success is, once again, that the digital team isn’t trying to force a proverbial square peg through a round hole. The clips play up the very features of Biden that people view as his strengths: empathy and managerial experience. And they do so in a format that’s comfortable to the audience.

“Our base, the people who engage with our content, the formats that they like most are Vox-y… also like Upworthy and NowThis,” he said. “So for us, the content architecture that we're going to build for the people who are our own audience is just really different than Trump's because our base and his base are just very different people... Doing what Trump does with memes, it would feel weird for us, it would look weird for us, and it's not what our audience responds to.”

But while Team Biden has found a groove in its video production operations, there remains glaring problems still to solve in its overall approach. The plurality of their video viewers on Facebook are women 65 and older. On Facebook, their largest growth in audience is older people.

That may simply be because Facebook’s audience is itself skewing older. But it also seems to be a byproduct of the calculations the campaign is making. Others running for the Democratic primary had different approaches. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) took pride in directly engaging audiences that weren’t always capital-D Democratic, figuring that the surest way to convert people was to talk to them. Former South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg built an entire campaign persona around the idea that he was willing to go everywhere and anywhere—no media hit too adversarial or, seemingly, obscure.

Then again, neither of them won. Biden did. And when it comes to elections, another 55-year-old swing-state suburban mother who the campaign convinces to cast a ballot is just as important as a college student from the same state that they persuade to go to the polls.

Still, Flaherty acknowledges that there is work to be done in generating interest among progressives and younger voters; that it is, in his words, “not enough for us to spend our time making content for my grandmother.”

But herein lies the balancing act that Biden’s team must perform. Can they reach those audiences without the candidate actually appearing on the platforms those audiences increasingly use? More importantly, can the campaign and the candidate talk about the issues that matter to young people and minorities in ways that don’t feel distant or patronizing?

The Breakfast Club snafu aside, that’s certainly the hope. It’s why instead of going on TikTok, Biden sat down with soccer star Megan Rapinoe on her Instagram live feed—a choice, Flaherty said, that was made in part to reach young women voters. It’s why Biden won’t likely be a guest anytime soon on Chapo Trap House (“probably not” said Flaherty) but will try and reach progressives through livestreamed conversations with Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA). It’s why some groups, like the youth turnout organization NextGen, will do drag shows on Twitch and others—mainly, the Biden campaign—will take a pass.

“NextGen ought to be doing that,” said Flaherty, “it’s super smart. But if Joe Biden hosted a Twitch drag show that would be weird. But if Joe Biden had a real serious policy conversation with a streamer about issues in the gaming community, like that’s just less weird.”