Right in the middle of Bill Buford’s recently published book Dirt, I came across something I think might irrevocably change my life—in fact, change all of our lives. Not in a tremendous, Earth-shattering, I-found-the-coronavirus-vaccine way, but in a daily, almost pedestrian way. Before we get to that, some context about Buford.

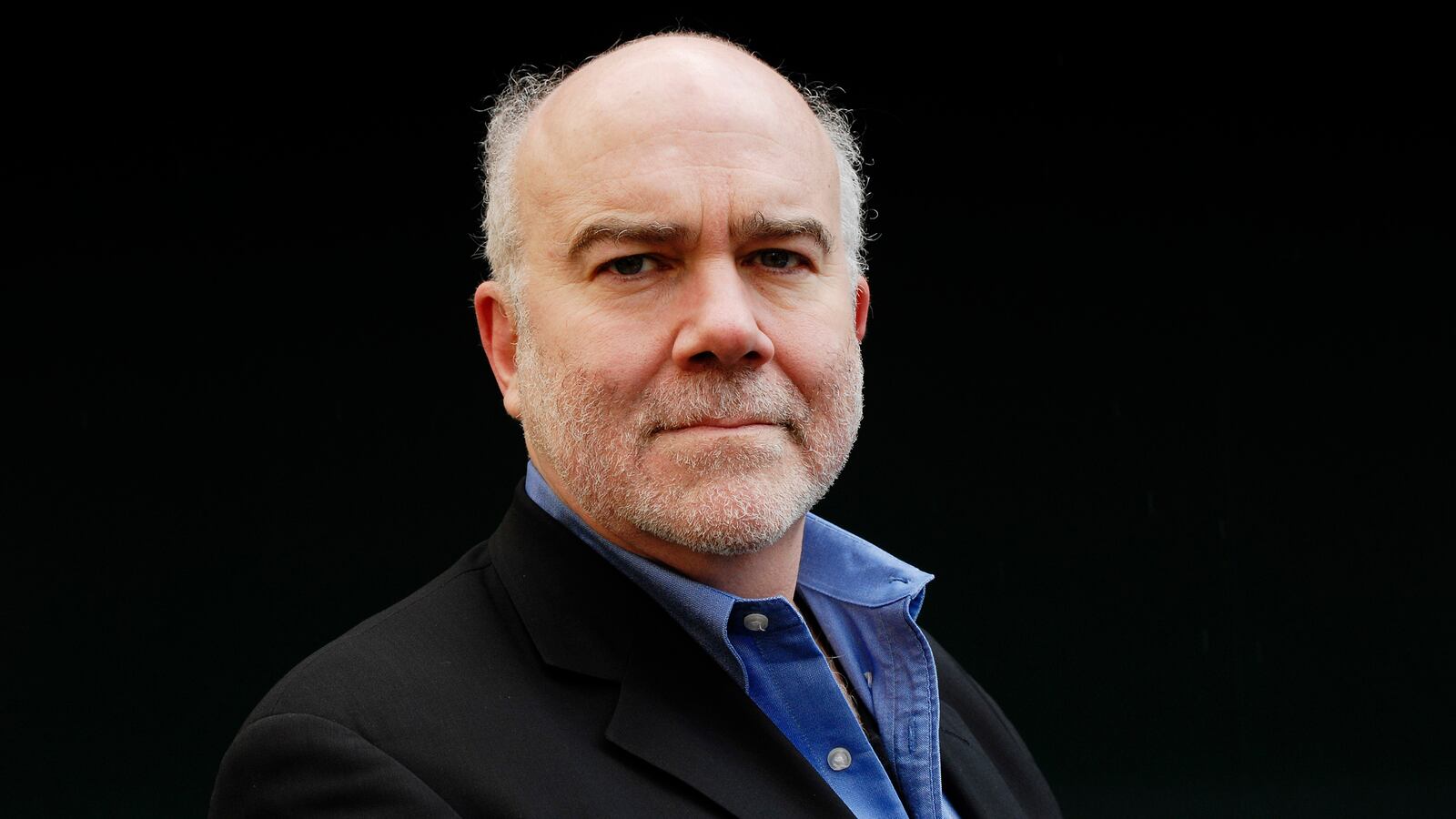

About two decades ago, Buford found himself first with a New Yorker magazine assignment to work in the kitchen at Mario Batali’s Manhattan restaurant Babbo and then with a deal to expand the experience into a book. He got so deeply involved in the food world that he ended up in Italy learning from a traditional butcher. The project became more than just a gig. This was par for the course, since Buford takes his time. To research his previous book, Among the Thugs, he spent eight years running with English soccer hooligans.

The resulting work, the rollicking Heat, ended with a note about how Catherine de’ Medici moved from Italy to France and taught the French how to cook. In the margin of my copy, I had written 14 years ago, “ah, so he’s going to France to do it again.”

Somewhere over the course of the intervening years, I stopped expecting that book.

In fact, it almost never happened. Buford found it difficult to infiltrate the kitchens of France. For one thing, chefs weren’t impressed with his Italian credentials or experience. So he had to move to France to do it and also, um, learn French—and do it all with preschool-aged twins and a wife in tow.

That he began working on the book at all is, even in the middle of reading of it, somewhat of a surprise—you’re holding it, you know it happens and yet…

No one would expect restraint from Buford—he is not the sort to take a tour, skim the press release and call it a day—but this dive is deep even by his standards. He lived in France long enough for his sons to think and dream in French, for them to have different handwriting (better) in French than they do in English. Long enough to make real friends, to learn the language (sort of) himself, and to come teeteringly close to running out of money. He was, after all, working as a stagiare, the classic French system of apprenticeship during which a young chef works in the kitchen of an established chef to cut his teeth and gain imprimatur. In those kitchens, one works all day, every day, six days a week—worth doing for free if you’re a youngster trying to become a grand chef, but it’s a little rockier of a proposition if you are a middle-aged father.

What’s more, the work, while rewarding, comes with a culture that runs on humiliation and machismo. At one key moment, the cook he’s working next to dismisses him. “Made to stand in the corner by a nineteen year old,” he said. “It was really dark.” It’s a climactic scene, and ultimately hinges on whether or not Buford is going to follow the instruction of their superior and punch his co-worker. (It wouldn’t feel right to spoil what happens next—the tension is so visceral.)

I read Dirt during the coronavirus lockdown, which was a double-edged experience. On the one hand, it was a marvelous journey that took me far away from my home. Part of Buford’s charm is that while he is as obsessed with food, he is perhaps even more obsessed with books and history. He brings to his scholarship the same exuberance he brings to the table, and as much as he loves both research and eating, I suspect he loves words even more. His work is writerly first, a book meant to be read from cover to cover.

But the other edge was that reading it made me want to travel and it made me want to shop. I wanted to peer into a butcher’s case to see what looks right, I wanted to scour market tables for good cherries, to talk to a cheesemonger… I shrugged it off, of course, since I’d rather wait to see the cheesemonger than endanger one.

It struck me, however, that a man so curious, and so good at finding ways to get and stay interested, might have some insight into how we can all invigorate our own kitchens.

Obviously, he’s found a way to keep from being bored during the coronavirus. So, what is he doing now?

Turns out, in addition to cranking out “Kitchen Notes” for the New Yorker, he’s been baking, like all of us, but that’s not all.

Buford has “little obsessions. Maybe not so little.”

Specifically, he’s obsessed with chicken. One of the most riveting meals in Dirt takes place in a high meadow of the Jura mountains, where Buford has walked to track the footsteps of Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin. He has bought a chicken sandwich, which he describes as the best he’s ever had.

He didn’t spec it out in the book, so I asked him what made it so special. “Lots of fatty chicken—in a good way,” he told me. “Mayo, homemade. A big hunk of bread. My toes are going tingly.”

Chasing that taste, recently at home he has been cooking the French Bresse chicken in broth, trying to find the magical moment when the breast is still edible and the legs are cooked. “The Bresse is only a little better than a very good chicken, but all the very good chicken is a lot better than the rest of it.”

In Dirt, he explains that the “roasted” poulet de Bresse Demi-Deuil (a chicken with truffles tucked under the skin, one of the cornerstones of French cooking) is cooked as if it were “two birds. Actually, it is a trick of presentation to make it seem as though it were one. It also isn’t roasted.”

On the phone with me, he talked about how you learn to recognize, from the vapor coming off the pot, when the chicken is cooking perfectly and how long it will take. His most successful bird, so far, was the one that he boned out, stuffed and rolled back up.

Recently, he’s also been making stock, or rather, keeping it. He’s got a stock that he replenishes every week, saving a bit of last week’s like a setback in whiskey, or the hunk of yesterday’s dough that his Lyonnais boulanger used to start today’s loaves. In this way, it becomes not just a stock, not just any broth, but the base of all of your dishes.

Of course, such activities lead to arguments about freezer space and storage, and it is about this that Buford has led me to a path from which I hope to never falter.

He was charged, during the course of his stage, with the production of the staff lunch, which, on Fridays, is to be made of the leftovers from the week. The French, it turns out, have a philosophy of leftovers. It’s in the textbook Buford used at the Institut Paul Bocuse. (There’s even a book from 1899, The Art of Using Leftovers.) It is important, for instance, to “never store a leftover in a serving dish or cooking vessel; never reuse a preparation made with raw egg; never keep anything for more than three days; and, the most important of all: Never, under any circumstances, use a leftover twice. A leftover has one chance,” Buford writes, “to be made even better than the original.”

I told him he’d blown my mind with that last one, and he laughed in agreement.

“It’ll change the way you think about it. It’ll change your relationship with your fridge.”