Harry Hopkins had nowhere near the rules and regulations we have now. (In 1933, Hopkins’ Civil Works Administration put 4 million to work in a month.) I don’t blame the people in the White House for problems in getting shovel-ready projects off the ground; sometimes it takes three years or more for the approval process. We should try to change this: Keep the full review process when there are real environmental concerns, but when there aren’t, the federal government should be able to give a waiver to the states to speed up start times on construction projects. We gave states waivers to do welfare reform, so by the time I signed the bill, 43 of the 50 states had already implemented their own approaches. We need to look at that.

Nick Ut / AP Photo

If you start a business tomorrow, I can give you all the tax credits in the world, but since you haven’t made a nickel yet, they’re of no use to you. President Obama came in with a really good energy policy, including an idea to provide both a tax credit for new green jobs and for startup companies, to allow the conversion of the tax credit into its cash equivalent for every employee hired. Then last December, in the tax-cut compromise, the Republicans in Congress wouldn’t agree to extend this benefit because they said, “This is a spending program, not a tax cut. We’re only for tax cuts.” It was a mistake. The cash incentive worked. On the day President Obama took office, the U.S. had less than 2 percent of the world market in manufacturing the high-powered batteries for hybrid or all-electric cars. On the day of the congressional elections in 2010, thanks in large part to the cash-incentive policy, we had 20 percent of global capacity, with 30 new battery plants built or under construction, 16 of them in Michigan, which had America’s second-highest unemployment rate. We have to convince the Republican Congress that this is a good thing. If this incentive structure can be maintained, it’s estimated that by 2015 we’ll have 40 percent of the world’s capacity for these batteries. We could get lots of manufacturing jobs in the same way. I could write about this until the cows come home.

Paul Sancya / AP Photo

When I was president, the economy benefited because information technology penetrated every aspect of American life. More than one quarter of our job growth and one third of our income growth came from that. Now the obvious candidate for that role today is changing the way we produce and use energy. The U.S. didn’t ratify the Kyoto accords, of course, because Al Gore and I left office, and the next government wasn’t for it. They were all wrong. Before the financial meltdown, the four countries that will meet their Kyoto greenhouse-gas emission targets were outperforming America with lower unemployment, more new business formation, and less income inequality.

Rick Bowmer / AP Photo

Just look at the Empire State Building—I can see it from my office window. Our climate-change people worked on their retrofit project. They cleared off a whole floor for a small factory to change the heating and air conditioning, put in new lighting and insulation, and cut energy-efficient glass for the windows. Johnson Controls, the energy-service company overseeing the project, guaranteed the building owners their electricity usage would go down 38 percent—a massive savings, which will enable the costs of the retrofits to be recovered through lower utility bills in less than five years. Meanwhile, the project created hundreds of jobs and cut greenhouse-gas emissions substantially. We could put a million people to work retrofitting buildings all over America.

Spencer Platt / Getty Images

Let’s suppose you and I go to a blue-collar neighborhood in Rockland County, N.Y., about an hour north of midtown Manhattan. On each house we could do a simple job—in and out in a day—that would almost certainly save 20 percent in energy costs. You wouldn’t even need banks if states required the electric companies to let consumers finance this work through utility savings. At least 11 states allow the electric companies to collect the money saved and use it to pay the contractors. So why shouldn’t the utilities finance this? To give another example, our climate-change initiative worked with the state of Arkansas, with the support of the governor, to develop a program called HEAL (Home Energy Assistance Loan), in which a company first creates jobs by making its own building more energy-efficient. Then, with the savings from the utility bill, they establish a fund to offer interest-free loans to their employees to finance the same work on their homes. This could be done with a little government support by companies all over the country. You get 7,000 jobs for every billion dollars in retrofitting. Let’s start with the schools and colleges and hospitals, and state, county, and local government buildings. That would keep the construction industry busy for a couple of years, creating a million jobs that would ripple through the whole economy, spurring even more growth.

Simon Burt / AP Photo

There may be some things that the states can do to loosen this up. One of the reasons Harry Reid won in Nevada is that, right before the election, two big Chinese companies announced they were moving factories there to make LED lightbulbs and turbines for the big wind farms down in Texas. Nevada is a little state, and it gained more than 4,000 jobs.

The thing I really liked about it was that the Chinese guys played it straight. They said the decision was pure economics. They didn’t say, “We’re coming here because Harry Reid is the leader of the Senate.” They said, “We’re coming here because Nevada has the best state incentives to go with the federal incentives.” They were very clinical. They said labor costs in China are still cheaper, but these turbines are big and heavy, and higher transportation costs to the U.S. market would offset the labor gains—and there was a tax credit from the federal government for green-energy manufacturing, and extra credits in Nevada.

Will Vragovic / AP Photo

Before the last presidential election, I tried for a year to get both Congress and the administration to deal with the fact that the banks weren’t lending because they were still jittery about the economy, and worried about the regulators coming down on them for bad loans still on the books. It’s not much better now. Banks still have more than $2 trillion in cash uncommitted to loans.

So I suggested that the federal government set aside—not spend—$15 billion of the TARP money and create a loan-guarantee program that would work exactly the way the Small Business Administration does. Basically, the bank lends money to a business after the federal government guarantees 75 percent of it. Let’s say that the SBA fund has about a 20-to-1 loan-to-capital ratio, and it’s never come anywhere near bankruptcy. If we capitalized this more conservatively at 10-to-1, we could guarantee $150 billion in loans and create more than a million jobs. We should start with buildings we know will stay in use: most state and local government buildings, schools, university structures, hospitals, theaters, and concert halls. We could include private commercial buildings with no debt. Even if many are strapped for cash, allowing the costs of the retrofits to be paid only from utility savings means the building owners won’t be out any cash. It’s a “just say yes” system.

John Raoux / AP Photo

Look at the tar roofs covering millions of American buildings. They absorb huge amounts of heat when it’s hot. And they require more air conditioning to cool the rooms. Mayor Bloomberg started a program to hire and train young people to paint New York’s roofs white. A big percentage of the kids have been able to parlay this simple work into higher-skilled training programs or energy-related retrofit jobs. (And, believe it or not, painting the roof white can lower the electricity use by 20 percent on a hot day!)

Matt Rourke / AP Photo

I’m sympathetic with the objectives of the Bowles-Simpson commission; we do need to do something about long-term debt. It’s a question of timing, really. If we cut a lot of government spending while our economy still has so little private investment, we risk weakening the economy even more and increasing the deficit because tax revenue can fall more than spending is cut. That’s why the Bowles-Simpson report recommends we delay big spending cuts until next year. So what should we do? More infrastructure initiatives now would put a lot of people back to work. But President Obama doesn’t have the votes in Congress to get another stimulus package. When asked why he robbed banks, Willie Sutton said, “Because that’s where the money is.” We have to unlock that money and take steps to get U.S. corporations to invest some of the $2 trillion they have accumulated.

Paul Sancya / AP Photo

Andrew Liveris’ book on how we can bring manufacturing back to America cites a company that interviewed 3,600 people for 100 jobs and hired 47; the others didn’t have the necessary skills. One answer to the skills roadblock comes from the former labor commissioner in Georgia, Michael Thurmond. After job vacancies go unfilled for a certain period of time, the state offers businesses the money to train potential employees themselves. During the training period, the companies don’t become employers, so they don’t have to start paying Social Security taxes or employer benefits. They train people their way, then hire those who succeed as regular employees, reducing the time lag between when a job is advertised and when it is filled. With unemployment at 9 percent and the real rate of those without full-time work higher, there are 3 million posted job vacancies. Filling them faster could make a big difference.

Rick Bowmer / AP Photo

I’m trying to figure out why job seekers don’t have the skills companies need; why the community colleges and vocational programs, which have done such a great job for America, are not providing more people with the skills to fill these vacancies. Do people just not enroll in the right programs or do they drop out because of the economy? I hope we can find out.

Rich Pedroncelli / AP Photo

It’s true that our corporate rates are the second-highest in the world. But it’s also true that what our corporations actually pay is nowhere near the second-highest percentage of their real income in the world. So I’d be perfectly fine with lowering the corporate tax rates, simplifying the tax code, and saving some money on accountants, but broadening the tax base so that all of them pay a reasonable amount of tax on their profits. That’s what the Bowles-Simpson commission recommended, and it’s the right policy. Lower the rates to be competitive, but reduce the loopholes that cause unfair disparities. We all need to contribute something to help meet our shared challenges and responsibilities, including solving the debt problem.

OECD

We lost manufacturing jobs in every one of the eight years after I left office. One of the reasons is that enforcement of our trade laws dropped sharply. Contrary to popular belief, the World Trade Organization and our trade agreements do not require unilateral disarmament. They’re designed to increase the volume of two-way trade on terms that are mutually beneficial. My administration negotiated 300 trade agreements, but we enforced them, too. Enforcement dropped so much in the last decade because we borrowed more and more money from the countries that had big trade surpluses with us, especially China and Japan, to pay for government spending. Since they are now our bankers, it’s hard to be tough on their unfair trading practices. This happened because we abandoned the path of balanced budgets 10 years ago, choosing instead large tax cuts especially for higher-income people like me, along with two wars and the senior citizens’ drug benefit. In the history of our republic, it’s the first time we ever cut taxes while going to war.

Charles Dharapak / AP Photo

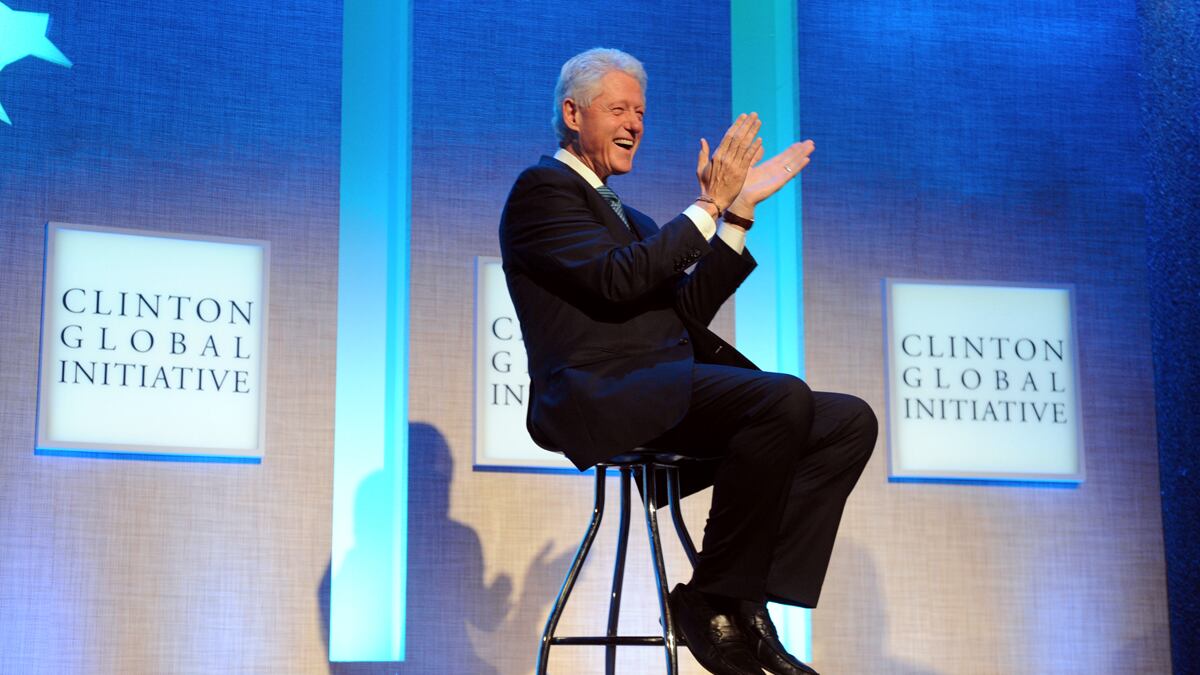

I’m hosting this month’s CGI America meeting on the assumption that there will be no federal stimulus and no further tax incentives targeted directly toward creating new jobs. Going on these assumptions, we want to analyze America’s economy: What are our assets? What are our liabilities? What are our options? There must be opportunities to be tapped, given all the cash in banks and corporate treasuries. If we have some success, we might be able to influence the debate in Washington in a nonpartisan way because we’ll have economic evidence to show them. I don’t have any problem at all if Congress wants to give tax credits to companies that actually hire people. But I think we have to pay for them, so I’d be happy to go back to the tax rates people at my income level paid when I was president in order to pay for the tax incentives to put more people to work.

Michael Reynolds/ Getty Images