Through the use of a bionic finger, scientists have created the ability for amputees to feel textures. It’s a huge leap for the world of the prosthetic touch, and a powerful indicator of how far we’ve come in understanding the brain.

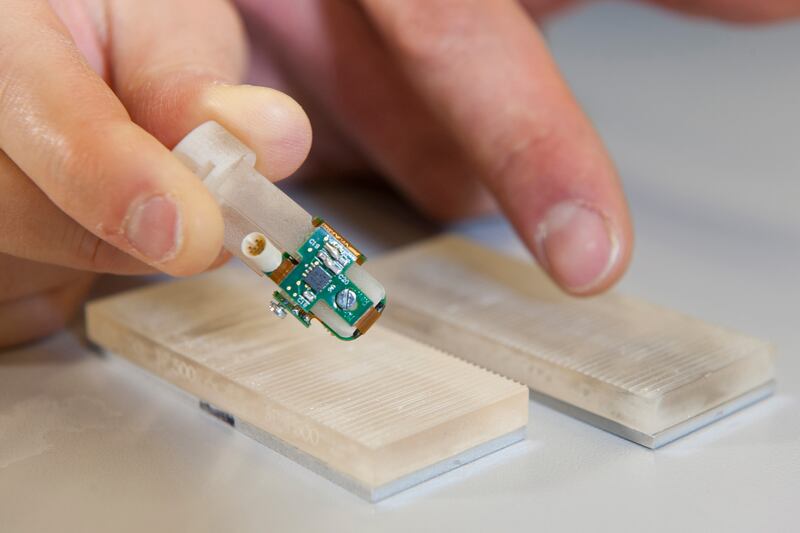

The study, published Tuesday in the journal ELife, was a joint effort between scientists at the Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna (SSSA) and the Swiss Federal Institute of Tech in Lausanne (EPFL). To conduct it, the scientists surgically implanted electrodes into the upper arm of Dennis Aabo Sørensen, whose arm had been amputated below the elbow.

In a video of the event, a machine moves an artificial bionic finger across two types of lines on a plastic strip—some close together, the others far apart. The movement of the fingertip generates an electrical signal, which translates into a series of electrical spikes. Sent to the brain, the spikes mimic the language of the nervous system and create the sensation of feeling.

Later in the video, Sørensen describes the process. “When the scientists stimulate my nerves I could feel the vibration and sense of touch in my phantom index finger,” he says. “[It] is quite close to when you feel it with your normal finger you can feel the coarseness of the plates and different gaps and ribs.”

The research differs from previous experiments, many of which aim to produce feeling through an actual bionic hand. DARPA, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, successfully created a bionic hand that allowed a paralyzed 28-year-old to feel touch. But unlike the electro-powered bionic finger, the hand did not allow the volunteer to feel specific textures.

With the electrode implanted, Sørensen was able to feel both smooth and rough services, successfully distinguishing between the two 96 percent of the time. He says the process felt even more like real touch because the memory of his missing limb remains. “I still feel my missing hand, it is always clenched in a fist,” he said. “I felt the texture sensations at the tip of the index finger of my phantom hand.”

In earlier studies, Sørensen was given a bionic hand that allowed him to feel and recognize various shapes and softness. But the ability to distinguish between textures is considered by scientists to be a “superior level of touch resolution.” Silvestro Micera, a professor at EPFL Switzerland and SSSA Italy as well as one of the lead researchers, called texture discrimination a “sophisticated part of the sense of touch,” one that’s only possible (as of now) through the implanted electrode.

To test the efficacy of the experiment in non-amputees, the scientists attached fine needles to their arms, connecting them to the main nerve. While still able to feel the sensation of texture, the non-amputee group had more difficulty distinguishing between smooth and rough—succeeding only 77 percent of the time.

Despite the discrepancy, the scientists saw the second experiment as a potentially different way to achieve the same result, one that would require less work. Calogero Oddo of the BioRobotics Institute of SSSA expressed hope that the discovery would yield even bigger things in the future.

“This study merges fundamental sciences and applied engineering: it provides additional evidence that research in neuroprosthetics can contribute to the neuroscience debate, specifically about the neuronal mechanisms of the human sense of touch,” said Oddo. “It will also be translated to other applications such as artificial touch in robotics for surgery, rescue, and manufacturing.”

The discovery comes just six months after a professor in the Department of Ocean and Mechanical Engineering at Florida State University created an authentic-looking robotic finger using a 3-D printer. Suffice to say, for the prosthetic limb community, the future is bright.