Last week, I spent a day trying to use The Negro Travelers' Green Book, and I’m happy to say I failed miserably.

The book is useless now as a guidebook. The establishments it listed are mostly gone. More important, the clientele it served—African American travelers searching for housing and food in the era of segregation—doesn’t need it anymore.

That, however, does not mean that the Green Book has no value. On the contrary, while its original purpose may be antiquated, its new service as a field guide to the daily and ubiquitous indignities suffered under Jim Crow make it invaluable.

If there is any tragedy here, it is that most people today are blissfully unaware that such a guide ever existed, much less that it thrived for three decades and was so popular that 15,000 new guides were published every year.

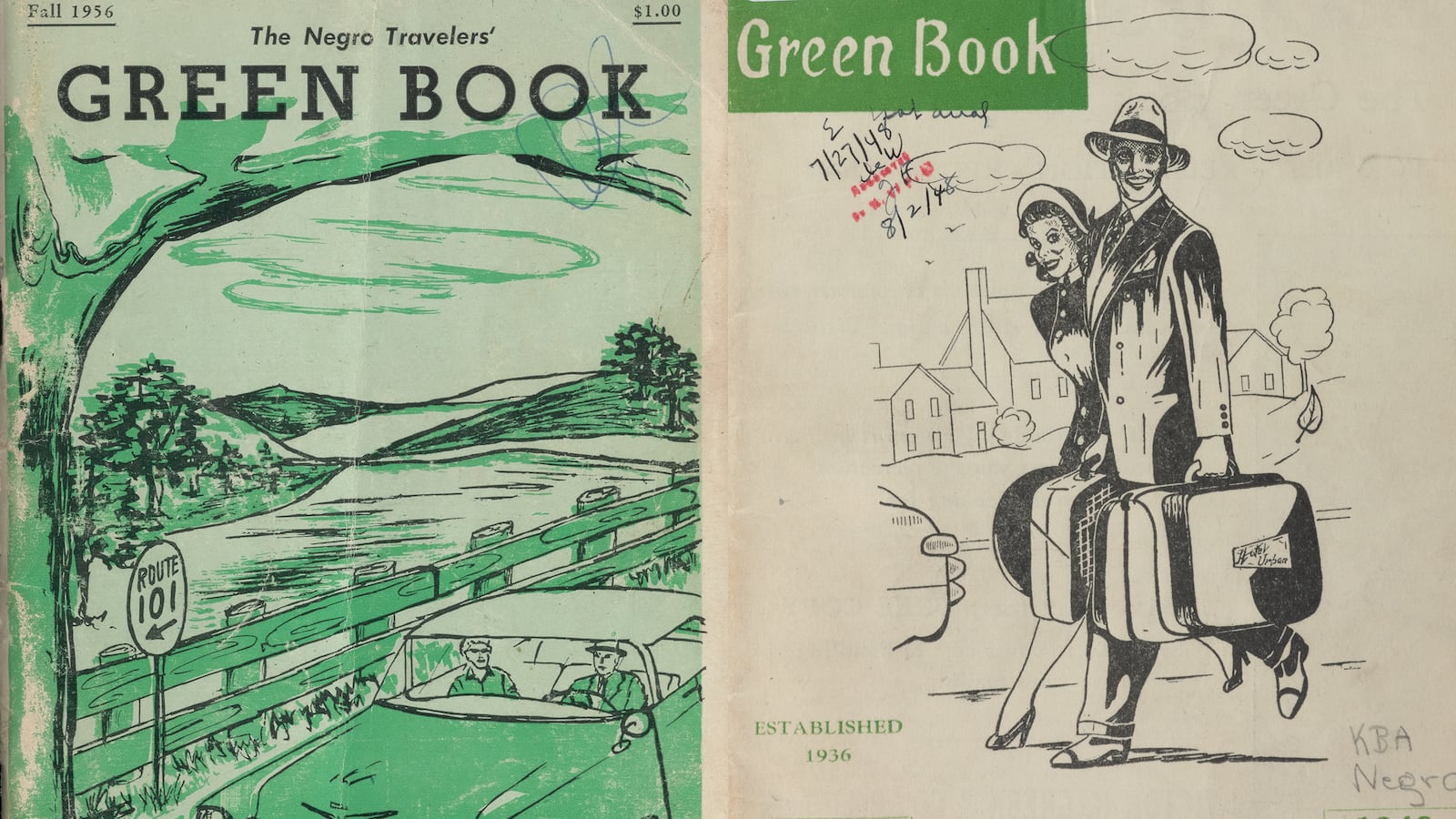

It all began in 1936, when a Harlem postal worker named Victor H. Green published his first Negro Motorist Green Book (the name was later changed to The Negro Travelers’ Green Book).

Patterning his guide on similar publications for Jews, Green published new editions annually until his death in 1960, and his wife continued the business until 1966.

The Green Book listed hotels, motels, restaurants, barbershops and beauty parlors, tailors, road houses, guest houses, trailer parks, service stations, theaters, dance halls, garages, and taverns where African American travelers could be sure they would not be turned away because of their skin color.

Or, as some editions put it on the covers: “For vacation without aggravation.” Or, more pointedly: “Carry it with you… you may need it.” The title page promised “Assured Protection for the Negro Traveler,” while text inside assured readers that using a Green Book would allow them to travel “without embarrassment.”

Green’s earliest editions identified only places east of the Mississippi where African Americans would find the welcome mat out, but over the years he expanded his directory to include the whole country. He also published a vacation guide, a railroad edition, an airline edition, and ultimately an international edition.

Today actual copies of Green Books are rare enough to be collectible, but the University of South Carolina has posted the 1956 edition online for several years. And now the New York Public Library, as part of its new online Public Domain Collections project has posted 22 editions of the Green Book, from 1937 to 1964. There is also a documentary film in the works, by director Becky Wible Searles and author Calvin Alexander Ramsey, who has also written a play and a children’s book, Ruth and the Green Book about the guide.

The first couple of editions simply sold ad space for merchants in the New York area, but by 1938, Green was publishing an extensive state-by-state directory of tourist-trade merchants willing to cater to Black travelers.

The list of establishments grew a little each year, and there were roughly as many establishments in the North as in the South, which tells you that traveling while Black was difficult no matter which point of the compass you picked.

For my trip, I first thought I might drive to New Jersey or Pennsylvania or, closer to home, Connecticut. The listings for all those places were plentiful. But then I saw that there were even a lot of listings, even in late editions, in Westchester County, where I live.

So I began by driving 10 minutes from my house to 2 Water Street in Ossining, the site of the Depot Square Hotel, which was located a block or so from the railroad station. The building standing at 2 Water Street is old enough to have housed the Depot Hotel in the late ’50s, but is now occupied by a laundromat and apartments. Here, as elsewhere on the journey, there was no one around to answer questions.

I continued on to White Plains, Green Book in hand, but the ravages of time had gotten there ahead of me.

Tarks’ Restaurant, an eatery so good that some of its recipes have found their way into soul food cookbooks, has been replaced by an auto repair shop.

The site of the Winbrook Restaurant is now a vacant lot. A city parking garage and a government building now occupy the sites of the Waldorf Restaurant and the 4 Leaf Clover Restaurant.

I got a little excited when I got to the site of the Tarry Rest Motel, which is still occupied by another motel, the Alexander, but the clerk behind the Plexiglas window had no information about a possible predecessor, and the owner was nowhere to be found.

The Del Rio Hotel site is also a vacant lot. Ironically, the Del Rio stood a quarter mile from Gen. George Washington’s Revolutionary War headquarters, which, while currently undergoing some repair, is certainly still standing.

It struck me, as I drove home, that if we can devote so much attention to a building briefly occupied by Washington, surely we can spare a few plaques to memorialize the hotels, restaurants, and other establishments where Blacks were spared, for a night or just the duration of a meal or a haircut, the indignities of segregation.

Better yet, why not make Victor Green’s inspired guidebooks required reading in America’s public schools? What better way to teach children about the ravages of a time when merely setting foot in the wrong restaurant or trying to use a gas station bathroom could get a careless traveler jailed or worse just because his skin happened to be the wrong color? That Victor Green had to go to the trouble he did, and that thousands upon thousands of grateful travelers used his guides for decades, speaks volumes about the quotidian indignities that are so much a part of this country’s history.

In the first edition of his travel guide, Green wrote, “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal rights and privileges in the United States.”

He did not live to see that happen, but doubtless he would be happy to know that his Green Book was ultimately rendered useless. He might be happier still if he knew that as a history book, his guide’s value only grows with time.