Media

Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

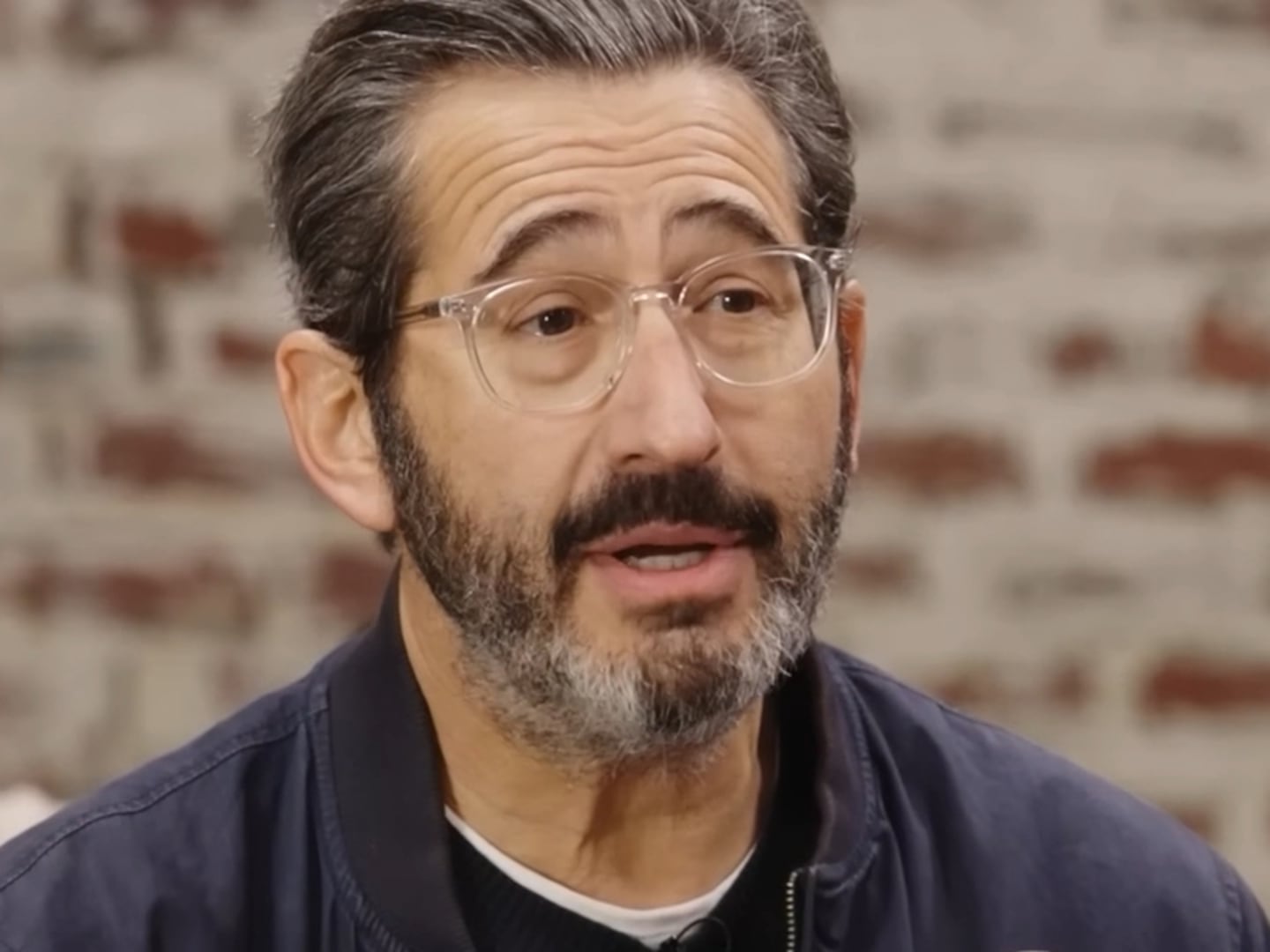

Black Analyst Says Condé Nast Used Bogus Stolen Oatmeal Claim to Fire Him

‘DISRESPECTFUL AND RUDE’

In a new lawsuit, Bradley Bristol claims he was retaliated against for having complained about allegedly discriminatory treatment by his boss.

exclusive

Trending Now