Lately, Bob Dylan, the globe-trotting rock star, has been painting pictures of his travels. A lot of them look like what you’d find on any retiree’s easel, set up by the Eiffel Tower or the Great Wall of China. A few come much closer to being serious contemporary art. You can tell, because they’re the ones that have been making headlines.

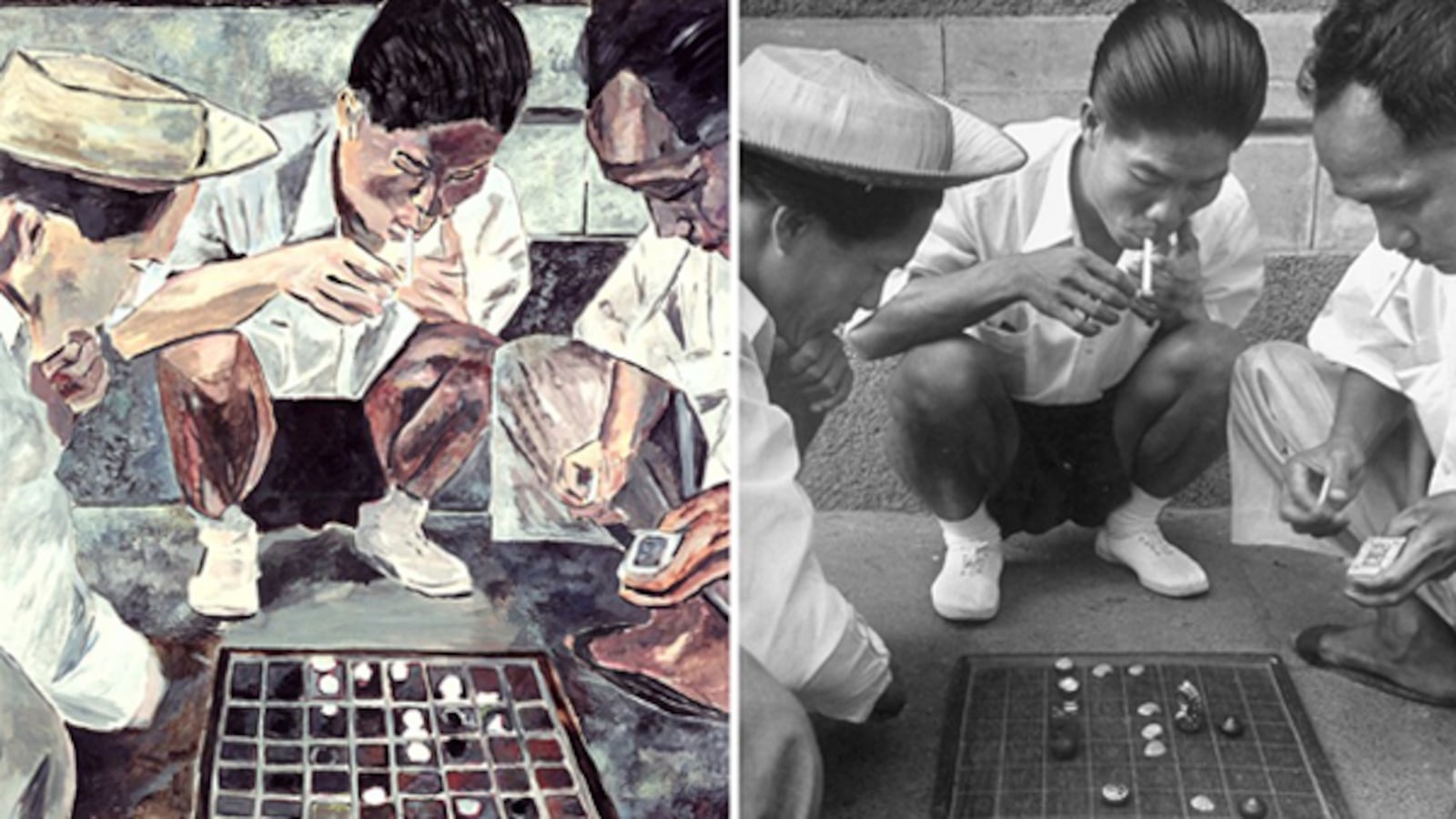

Various webizens have recently been raising a stink because some of the paintings in Dylan’s new “Asia Series,” now showing at Gagosian Gallery in New York, turn out to have been based on other people’s photos, as reported in Monday’s New York Times. A painting of two old men, called Trade, was closely based on a 1948 image by the great French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. One called Opium has now been “outed” as a copy of a vintage photo of an opium den by Leon Busy. A Flickr user who goes by the name Okinawa Soba has complained that fully six of Dylan’s sources seem to have been fished from Soba’s photostream, where he had posted images of vintage Asian photographs he owns.

All this led the Huffington Post to warn that the paintings may be “plagiarized,” and therefore “stunningly unoriginal.” A headline in Artinfo.com asks if Dylan’s painting are “ripped off.”

They aren’t. They are mainstream contemporary art. Ever since the birth of photography, painters have used it as the basis for their works: Edgar Degas and Edouard Vuillard and other favorite artists—even Edvard Munch—all took or used photos as sources for their art, sometimes barely altering them. Some of Matisse’s greatest works riff on cheap postcards of North Africa.

And that’s just the prehistory of the more aggressive, explicit borrowing that more recent painters have got up to. Warhol, of course, could barely have made paintings at all without well-known photographs to build them on. Gerhard Richter, possibly the greatest painter of our current era, used news photos of the Baader-Meinhof gang as the basis for one of his best series. Massimiliano Gioni, a curator at the New Museum of contemporary art in New York, said in an email that Richter’s photo-based paintings have “explored and analyzed in depth how photography and painting relate to each other: more importantly Richter has taught us to be somehow equally skeptical of the presumed objectivity of photography and of the subjectivity (and expressiveness) of painting. He has shown us that we can see and feel as machines, even when we paint, and that photos can be much more charged with emotion than we think.”

One year ago, one of the best shows in New York was the Metropolitan Museum’s giant retrospective of John Baldessari, a veteran Los Angeles painter who not only bases many of his paintings on photos, but often pays other people to paint them. He calls Dylan’s borrowings from photos a “no-brainer” that’s not worth a moment’s worry. “There are always going to be people who say art should be completely original. But what does that mean? Nobody comes out like the birth of Venus—all art comes out of art.”

Given his subject matter, Dylan’s “appropriations” may be especially cogent. By using old photos to explore the questionable notion of “Asian-ness,” Dylan locks onto the clichés at its heart, in a way he couldn’t have done by painting scenes from life. (By the way, you don’t need to know the exact sources for these paintings to see that they are based on photos. Many of them show obviously outdated scenes: Did Dylan really meet a Manchu couple, dressed in circa-1900 style, or observe a landscape full of kimonoed Japanese? Other images have compositions that are obviously photographic.)

The old photos let Dylan recycle standard Asian imagery in just the way our notions of Asian identity are based on recycled ideas. Dylan’s series becomes a kind of compilation of our views of Asia, tied together into a tidy package by the old-fashioned medium of oil paint—a cliché used to talk about clichés. Dylan isn’t a “good painter,” in the traditional sense, or no better than that retired-dentist uncle many of us have. And that weakness lets his pictures stand in for painting in general, rather than distracting us with any particular virtues. It is painting degree zero, just good enough to get its imagery across.

Let’s not forget that Dylan, the great pop musician, has always been a master of the cover version, copying whole songs and melodies and lyrics and even vocal stylings. Why wouldn’t he grasp the equal benefits in “covering” images by others, in his art? His only fault, in fact, is in not trumpeting those benefits.

Instead, he and Gagosian have been weirdly, naively coy. The show’s press release describes it as “a visual journal of [Dylan’s] travels” with “firsthand depictions of people, street scenes, architecture and landscapes.” In a hired-gun catalogue essay written by the great MoMA curator John Elderfield, Dylan cites a drawing teacher who told him to “draw only what you can see … draw it only if it is in front of you.”

Since the “plagiarism” story broke, statements from the gallery have just about admitted Dylan’s photographic borrowings, but rather than celebrating them they launch into the worst wall-label bromides: “the paintings’ vibrancy and freshness come from the colors and textures found in everyday scenes [Dylan] observed during his travels.”

Maybe the gallery is still smarting from a lost copyright lawsuit, now in appeals, in which Richard Prince, a Gagosian artist, got in trouble for basing his pictures on uncredited photos by someone else—a practice that is in fact the heart of Prince’s art, and that has won him a place in most major museums.

Here’s my favorite irony in this whole affair: That Dylan catalogue has an afterword by Prince, in which he waxes lyrical about his love for the musician and his paintings, which he compares to works by Arthur Dove and Cezanne. Prince never realizes that he himself may be the artist whom Dylan most nearly approaches.