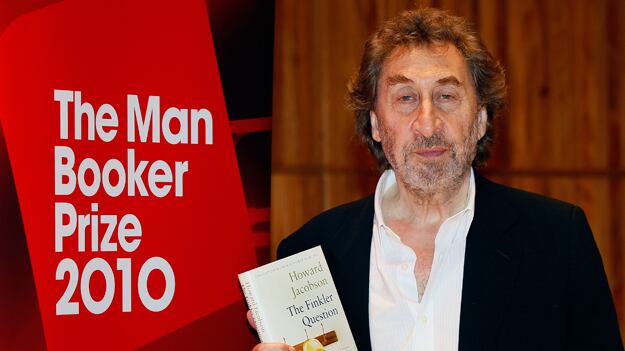

The Man Booker Prize this year was given to a dark horse winner, The Finkler Question by Howard Jacobson. Long praised for his comic novels and a favorite of such writers as Jonathan Safra Foer, this was the first time Jacobson was shortlisted for the prize, though an earlier novel, Kalooki Nights, made the longlist. His novel has only just been released in the U.S., but judging by sales of previous winners this is sure to become a bestseller. The novel follows three friends who gather one night to reminisce about their lives; one is robbed on his way home and from there unspools a work hailed by the Booker prize Chairman, Sir Andrew Motion, as, “very clever and very funny.” Undoubtedly Howard Jacobson is biting his own tongue after bemoaning that comic fiction wasn’t taken more seriously in last week’s Guardian.

Kirsty Wigglesworth / AP Photo

No, the date on this is not a typo. When the Booker was started in 1969, it was awarded retrospectively, to books published the year before the prize was announced. In 1971, the rules were changed, and the award has since gone to books published contemporaneously, the same year the award is given. Caught between the timing change were the unfortunate novels of 1970, which were never eligible. A mere 40 years later, the Booker committee atoned for its 1970 snub. In May 2010, the Booker Prize for 1970 was awarded to J.G. Farrell for The Troubles, an Irish comic masterpiece about a grand hotel in decline much like the country subsumed by violence around it. The win came 30 years too late for Farrell, who died in 1979, but the author didn't miss out on fame and the esteem of his peers. The second installment in his trilogy, The Siege of Krishnapur, won a Booker in 1973.

As the critics and bookies all predicted, this year’s winner was the heavily favored Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel, author of 12 acclaimed books. She beat out literary giants J.M. Coetzee and A.S. Byatt with a new novel, out next week in the U.S., based on the improbable rise and fall of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s trusted minister. It’s the literary set’s version of The Tudors, but will it find a similar blockbuster audience here in America? Yes, if previous winners are any guide.

Last year’s winner was Aravind Adiga’s debut novel, The White Tiger, told from the skewed but comic perspective of an Indian chauffeur who justifies his criminal, murderous methods for climbing India’s social ladder. “[The narrator’s] appealingly sardonic voice and acute observations of the social order are both winning and unsettling,” said The New Yorker at the time. Adiga stuck to murder as a theme with his second book, Between the Assassinations, a collection of short stories.

David Levenson / Getty Images

Former TV producer Anne Enright won the 2007 Booker for her fourth novel, The Gathering, which deals with what The Guardian described as “the horror of love” through complex jumps in perspective and time. Enright, who has written two books since, is known for her sensitive but highly physical writing: “It’s a joy to be with a book that combines the exalted and the profane so handily,” said the Guardian’s reviewer.

The daughter of novelist Anita Desai, who was shortlisted three times without ever winning, finally brought it home for the family when she won for The Inheritance of Loss. The book, which Publisher’s Weekly called “alternately comic and contemplative,” charts a hodgepodge of characters as they deal with the onset of huge political changes in 1980s India. Desai is reportedly dating another prize-winning author, Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk, so perhaps a joint work is in their future.

Diana Matar, PA / AP Photo

For his 15th novel, Banville finally won the Booker for The Sea, a classic British telling of a man’s boozy, sentimental exploration of the past (and, naturally, lost love), which The New York Times characterized as “almost numbingly gorgeous.” Some readers may be familiar with Banville’s occasional pseudonym “ Benjamin Black”, under which he writes dark thrillers set in his native Dublin. His latest novel is out in February.

Alan Hollinghurst has been one of the most respected authors and editors in England for the past two decades, well-known both for his lush, empathic writing style and for his graphic depictions of gay life in 1980s London. He took home the Booker in 2004 for The Line of Beauty, widely considered to be his best work to date. Among other things, The Line of Beauty marked the first time Hollinghurst directly addressed in his fiction the new reality of the AIDS crisis. It’s a brooding story but at the same time, in the words of Anthony Quinn, a “magnificent comedy of manners.”

Alastair Grant / AP Photo

For the second year in a row, a novel about a boy won, when DBC Pierre, the pseudonym used by Peter Warren Tinley, took the prize for Vernon God Little. This chilling tale of what happens when a young man is the scapegoat in his community for a mass murder he didn’t commit is told in a Texas vernacular. Pierre’s next book, Ludmila’s Broken English, didn’t get quite the same attention but covered similarly shocking themes.

Perhaps the biggest seller of recent Booker winners and soon to be an Ang Lee film, Yann Martel’s Life of Pi was a runaway hit with readers, who were drawn to this touching story of a young Indian boy stranded with a tiger on a boat in the Pacific Ocean for 227 days. Despite his extraordinary success, the author hasn’t published anything since, but he did recently receive a reported $3 million advance for a new similarly allegorical novel.

Alastair Grant / AP Photo

Hailed as “the great American novel,” Carey’s masterpiece is actually about Australian bush legend and folk hero Ned Kelly, but its echoes of frontier life and open vistas explain why some thought it was. Already a Booker winner for Oscar and Lucinda, Carey wowed the critics with what Janet Maslin in The New York Times called a “spectacular feat of literary ventriloquism.” Next April, Carey will publish Parrot and Oliver in America, which now that he’s a New Yorker could earn him a Pulitzer.

To launch the Booker in the new millennium, the judges chose a novel of a decidedly historical turn about an old woman recollecting her unhappy marriage and possible love affair in the 1940s. But this wouldn’t be an Atwood novel without a twist in the form of a dystopian novel-within-the-novel ostensibly written by the narrator’s dead sister that reveals long buried secrets better left in the past. Atwood has continued her run of dark novels with the recently released The Year of the Flood.

Dave Thomson / AP Photo