In the spring of 2011, I spent two days on the set of Breaking Bad in Albuquerque, N.M. A few weeks later, Newsweek published my long feature story about “the best program on TV, period.”

Some of what I heard and saw on set made it into my report. But most of it didn’t. As I was organizing my files the other day, I stumbled upon two in-depth interviews I conducted during my time in ABQ: one with Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan, the other with actor Bryan Cranston (a.k.a. Walter White).

Reading over the transcripts, I realized that there was a lot of thematic overlap between the two conversations—and that I’d only used a fraction of each interview in the published story. So, with Sunday’s finale fast approaching, I decided to combine my lost Cranston and Gilligan interviews into one big Breaking Bad extravaganza.

Below, Cranston and Gilligan discuss the show’s “experimental” origins; the significance of Walter White’s decision to teach; and how Breaking Bad accidentally became a modern Western. If you don’t know what you’re going to do with yourself once the series ends Sunday night—like me—read on. It’s the perfect way to cling to the best program on TV a little longer. Period.

THE DAILY BEAST: Vince, you once said that no one in their right mind would buy Breaking Bad and that you couldn’t imagine what you were thinking when you pitched it.

GILLIGAN: There are so many reasons why Breaking Bad should not have sold. I’m still to this day astounded and amazed that it came to exist. The fact that it centers on a 50-year-old man who makes a very modest middle-class income—that’s not very attractive, I think, to most network executives. They want shows about younger people with more disposable income. And the fact that Walt gets this very downer news in the first episode that he’s dying of cancer—unsexy to say the least. That’s another strike against us. And the fact that Walt takes this chemistry knowledge and, with the motivation that he’s dying, decides to cook crystal meth—arguably the unsexiest, nastiest, most unredeemable drug there is—is strike three.

There’s no reason this show exists. It’s kind of like in science, the old saw that aerodynamically speaking, bumblebees shouldn’t be able to fly. Clearly they do, but on paper it doesn’t look like they should. It’s the same with Breaking Bad. I’m amazed it exists at all.

Anyone who’s been watching TV for the past 10 or 15 years has become quite familiar with the antihero character. How is Walter White different from someone like, say, Tony Soprano?

GILLIGAN: That’s a good question. Our show owes a great debt to The Sopranos, like all the other shows that center on a flawed or somewhat antagonistic protagonist. If The Sopranos had not existed, I don’t think Breaking Bad would’ve been a harder sell--I think it would’ve been an absolutely impossible sell. You need someone to trod that path ahead of you.

But even though this is a time in television of darker anti-heroes, to me, Breaking Bad is very much an experiment. Television is historically good at protecting its franchise--about keeping it’s characters in a self-imposed stasis. So that shows can go on for many seasons--many decades sometimes--and continue onward for an open-ended amount of time. That’s what television is good at, and some of my very favorite shows have worked on that principle.

But Breaking Bad was designed from the get-go to be closed-ended. I never had it squared away in my mind just how closed-ended it should be; I never had an exact number of episodes or seasons in mind. But it’s a story of change, where you take a character from point A and you transform him, over who knows how many episodes, to point Z. And then you end your show.

That’s not what television does. So The Sopranos and Breaking Bad are certainly different in that respect. Even though they both center around an anti-hero, it’s a little like comparing an apple and an orange.

Also, Tony Soprano was born into his life. His mother and his father were well-acquainted with a life of crime. There’s a feeling with The Sopranos, it seems to me, of fate--that Tony is a creature of his environment. But Walter White is in a sense the opposite of that--someone rebelling against his environment and his nature and trying to be something he isn’t and perhaps wishes he was; someone he didn’t for the previous 50 years didn’t have the courage to be. It’s all about him feeling alive.

He thought he could contain it, but it keeps metastasizing.

GILLIGAN: Walt has a very rational mind. He’s a scientist. He wants to be in control of situations. More often than not, he’s not in control. But so much of his desire for change stems from a lack of control. And yet he also has this hubris that he can control things. As we often do, from time to time--these are all things we can relate to. We all yearn for some sort of control over our fate and our lives, and we can all sympathize with that.

Was there any sense from the start that the character would go further into the realm of being unsympathetic than on other shows?

CRANSTON: That was Vince’s intention. His very famous quote is “turning Mr. Chipps into Scarface.” I knew from our first meeting that was what we were going to do. And that’s why I was so excited about it—because I’d never seen that. Never in television history. Have you ever seen a character devolve into a completely different person?

Are there moments where you felt like something Walter White was doing was beyond what your conception of the character was? Where he surprised you?

CRANSTON: Yeah. That’s always the case. Walt surprises me a lot. I don’t do a lot of forward reading on the scripts, because this guy is on such a wild ride. He doesn’t know what’s about to happen next hour, let alone next day or week. For me to know too far ahead wouldn’t be advantageous.

Do you ever worry about the viewer losing his or her connection to the character?

GILLIGAN: Yeah. Absolutely. Breaking Bad is a show that hopefully gains new viewers with every episode and every new season. But if I’m being honest I have to think that we’re also losing viewers with every episode, because Walt does indeed get darker with every episode that we air.

It’s not that we’re trying to darken Walt for darkness’ sake--some of the plot twists we give the view, some of the awful things that he happens to do. We really are embarked upon an experiment. We’re actively involved in something that I like to think is somewhat unique: the transformation of a hero into a villain. We strive to be true to that. It’s sort of our mandate. You have to go forward with such an experiment with courage. You don’t want to back off from it at the 11th hour. And you certainly don’t want to back off from it because you get a bit of critical success and heightened viewership. You love all that, and you want it desperately. I want big ratings and positive reviews as much as anyone. But I’d feel bad if we softened Walt up in a desire to please more viewers.

So I think that does mean that with every season, with every episode perhaps, there are people who shake loose and say, you know what, this guy is too damn dark. I can’t root for him anymore. I liked it better when he was doing what he was doing for his family. But now I think that’s an empty statement and a lie, and I think that what’s he’s doing is for his own personal benefit, and I just don’t buy the reasons that he does what he does anymore.

But other people will see Walt as fascinating, first and foremost. Even if they find it harder and harder sympathize with him.

Bryan, it must be such a challenge for you as an actor to keep the audience’s sympathy.

CRANSTON: But that’s what we have to do. Sympathy—that was the old form. That was an absolute. That your protagonist has to have sympathy. Well, yeah, if he’s a true protagonist. In the case of Breaking Bad, it’s a blurry line.

The way I look at it is, we had to set the hook in order to catch the fish. The bait was an honest, caring, forthcoming man who just had a load of shit dumped on him, and he decides to do this crazy thing. And yeah, in the pilot, your sympathies are with Walt. You feel for him. “My God, what would I do? Maybe something not that crazy. But if I was desperate…” You kind of understand. You’re kind of siding with him. What the audience didn’t know is that we were going to take him on this journey downward. It would not have worked if we hadn’t already planted that hook. If we had picked up somewhere where he was already a drug dealer.

So after sympathy for Walt runs out, why does the audience keep watching?

GILLIGAN: I have to believe that Walt is ever interesting. His character is ever interesting to me. Bryan Cranston has to climb into his head everyday to play the part. My writers and I have to do the same thing, on a different level.

It’s a dark place to be sometimes, but it’s a fascinating place to be. Walt is a case study. He’s a very interesting, complex, damaged individual with a lot of wonderful facets that even when I feel “oh my god, this guy is dark,” I always feel this guy is interesting. It only increases--it only becomes increasingly interesting to me, the more I learn about him, the more I discover about him in writing about him and thinking about him. And I hope that is the case for most viewers, even as they perhaps lose sympathy for Walt—and I don’t blame them a bit if they do—hopefully they will continue to find him interesting, and hopefully more and more so.

We have an amazing ace in hole with Bryan Cranston himself. I knew from Day One that we needed not only an excellent actor--one who can play very dramatic moments and very comedic moments; who has an amazing range as an actor--but also I knew we needed an actor who was human and sympathizable and somehow allowed us to root for him. Who gave us the ability to root for him no matter what he did. And because of Bryan, Walt is always recognizably human, even if he is tremendously flawed as a character.

Do you think, then, that the key is not to have the audience sympathize with, but rather to understand him?

CRANSTON: Yes, to understand him. What we owe the audience is to be truthful.

OK, so you’re doing this experiment—you’re transforming a hero into a villain. But what is that experiment trying to find or show or prove, beyond just going dark? What’s the point?

It’s funny. The show goes increasingly dark, but what we do is not just for the sake of darkness. Transformation is interesting to me. The best thing I have to offer as a writer is to show the viewer things they haven’t seen before. That’s not just in my case. That’s the case of any writer.

It’s hard, if not impossible, to go out and reinvent the wheel every time you tell a story. And I’m not saying we’re doing that here. But if you put your mind to it, and you see a type of story that has not been told as often, if you find a path that is not so well-trodden, narrative-wise, then I think it’s incumbent upon you as a writer to take it. And it seemed to me watching television—and I’ve watched more television than anyone has a right to and enjoyed most of it; I’m a big fan of TV—but when I came to this realization that TV was good at promoting stasis in its characters, it was a logical next to think, “How can I do a show in which the fundamental drive is toward change, and the evolving of our character?”

So what’s my point? I guess the point of the experiment is to be different--to see where we can go, to see where it takes us. Definitely the experiment is not to see how dark we can go. That’s sort of an inadvertent byproduct, although one which was not unforeseen. If you take a normal, everyday guy and have him choose to become a meth cook and dealer, you don’t have to be Einstein to figure out that if you’re honest about it is going to go pretty damn dark. But that was not the fundamental intention. The fundamental intention was to tell a different kind of story and see what that character would evolve into. To that end, it’s fun when Walt surprises us. It was fun to see how dark he would go in the early day, and nowadays it’s fun to look for the moments of humanity where he’s not quite so dark after all. To see those moments of change as they happen.

Bryan, what do you think? What’s the point of following Walt’s continuous downward journey?

CRANSTON: I think ultimately it’s an examination of the human soul and how, when we step outside of who we really are and degrade ourselves to a level that’s untrue to who we really are, bad stuff happens.

You see Walt’s decline as being untrue to who he really is?

CRANSTON: Who he really was. He allowed himself to be seduced. He’ll tell you, “I’m doing this for my family.” An altruistic “this is what I’m doing.” And he holds onto that tightly because if he lost that, then, “Why am I doing this?” You know? So he holds onto that, but he’s been stimulated by this journey as a man. It’s somewhat of an aphrodisiac to have power, as a man. It’s money, testosterone and adrenaline, pumping in his veins. Have you ever intimidated another person? I mean, gone up and said, “This is what you’re going to do, and if you don’t, I’m going to crush you?”

No.

CRANSTON: For most people, it’s rare. For Walt--the meek schoolteacher getting picked on and scrubbing the chalkboard with the kids laughing at him--now he can boldly walk up to someone and know there’s fire behind it. He can intimidate someone. That’s powerful.

My sense is that watching Breaking Bad helps the viewer understand why people do bad things. An act that might seem incomprehensible somehow becomes comprehensible when you know the person who’s committing it as intimately as we know Walter White. It’s a window onto something you don’t get to see in real life—like when you hear about a murder on the news and wonder how someone could have possibly done that.

GILLIGAN: It’s interesting how you put. I think you helped me realize... I’m as horrified and shocked and scared by really terrible violent criminal behavior as anyone. I read the newspaper just like anyone else and think, “My god, how far have we come here and where is it headed?” You read these stories of monstrous muggings and murders and rapes and all these terrible things, and you want to understand them on some level. It’s not a desire to sympathize with the agents of violence--

Or excuse it.

I have no intention of excusing misdeeds or murders. I just on some level want to understand why people do these things. You’re torn between wanting to understand them and recognize them as human beings, and part of you wants to write them off as human beings and say, “You know what, they’re just evil.” I don’t want to excuse their behavior in any way shape or form. I don’t want to hear they did what they did because they came from a broken home, or because they were illiterate. I have those conflicting feelings everytime I pick up the newspaper.

But I find that there’s an ancillary benefit to writing Breaking Bad. I don’t have any more empathy than I ever did for murderers that I read about in real life. But they don’t scare me in terms of being as bewildering monsters as they used to be. They don’t bewilder and terrify me quite as much as they used to. Because I feel like I’ve had some version of them in my head for the past four years. Not to say I want to live with them in my head forever. I think when Breaking Bad ends, there’s a lot about this show that I want to take off like a heavy overcoat and put away in a closet somewhere, figuratively-speaking. I don’t empathize with these real-life killers and drug kingpins any more than I ever did, but I recognize them as human. I wouldn’t necessarily say that’s a good thing or a bad thing. But on some weird level, as someone who lives in the modern world, it gives me some modicum of comfort, if that makes any sense.

CRANSTON: There’s some people out there who would say, “Screw it. I’d do what Walt did.” A take-it-to-the-man kind of thing. And then there are some who abhor my actions. Who say, “I cannot get behind your character.” But they still watch. Which is great.

That’s interesting. How do people still watch when...

CRANSTON: It’s like a car accident. They’re watching the disintegration of a man. It’s like [covers eyes], “Oh shit, oh god, ooh, wow, ooh.”

A vicarious thrill.

CRANSTON: It’s addictive. Our show is addictive.

How long do you think Walter White can survive?

CRANSTON: The day? 8:30, 9:00? [Laughs] He still has terminal lung cancer. That’s what he will die of, and in two years.

Do you ever get tired of living with such an intense character?

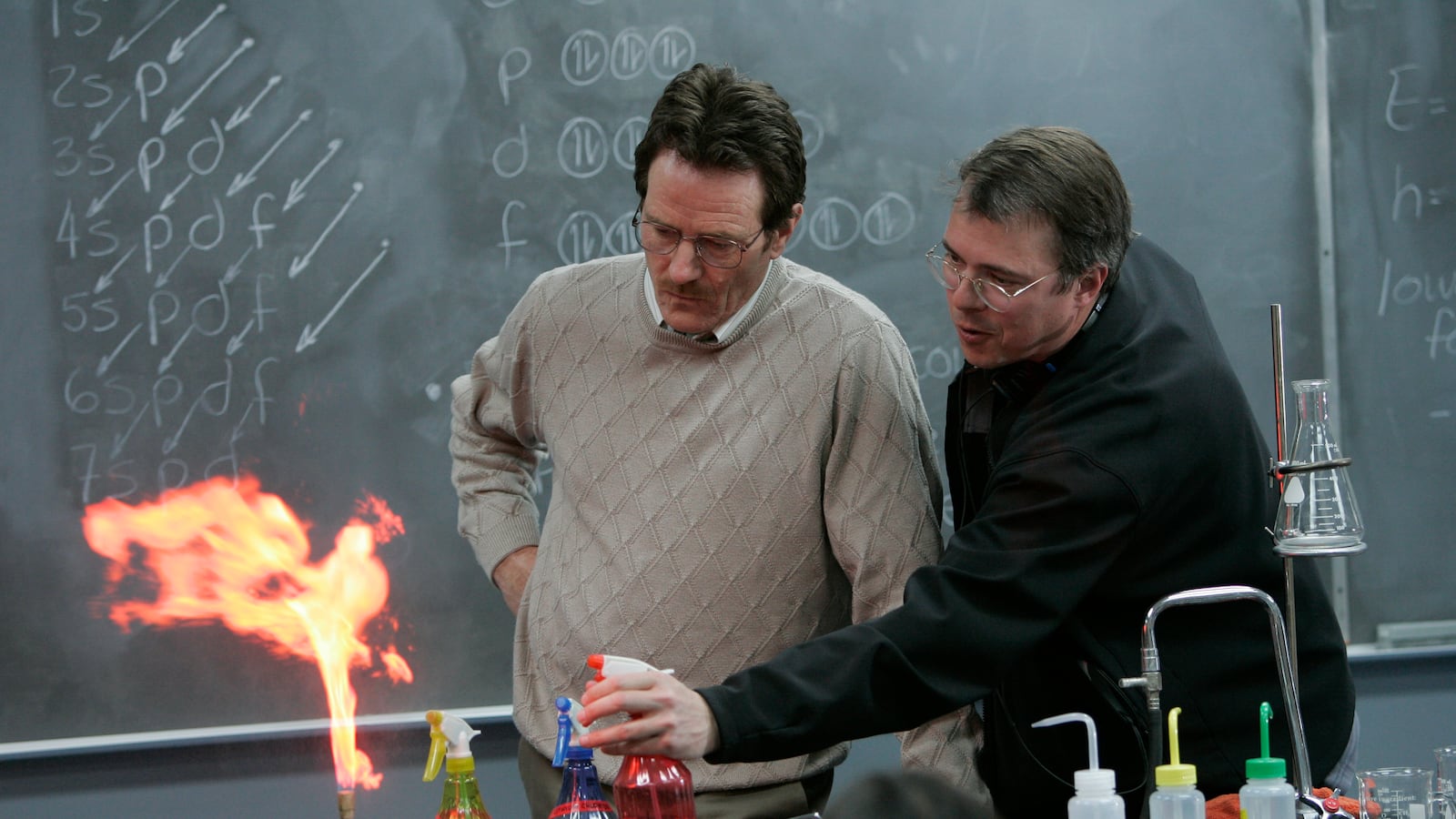

CRANSTON: No, I think I’ve done this a long time, so I let it go. I’m able… turning on a switch is too mechanical. It’s more like putting on comfortable clothes. A good pair of jeans and a sweatshirt. You’re comfortable in it, the shoes just fit right. It’s the same thing. I can step out of it and do something else. But when it’s time, oh yeah. I put this on and put these glasses on and pretty soon I’m in Walt’s head.

It’s such a mysterious process for those of us who can’t possibly imagine ourselves doing it. Have you discovered anything new as an actor doing this show?

CRANSTON: Our job as actors is to be able to observe human behavior and be able to replicate it. Our basic job out in the world is being observationists. You see something, you see behavior, and you say, “Oh that’s interesting.” You file it away. You study it. The way people react. The way that real people walk and talk and sit. It says a lot about someone.

I know color is a big thing for Vince. Is there any significance to Walt’s all-beige wardrobe?

CRANSTON: There’s a lot of significance to that. When you first saw me, I was also in beige. And that was by choice. I chose that. I wanted Walt to disappear. I wanted his color palette to be boring. Nothing stood out. This man is invisible to himself and society. And that’s why I wanted the mustache, the little thin... we thinned it out and thinned it out and lightened it...

It was just barely there.

CRANSTON: I wanted people to think, “What’s the point? What’s the point of this man? Where is this man?” Because he is one of those guys.

At the beginning of this show, Walt was depressed about the missed opportunities in his life. He had developed a fear of failure. All his life, every friend, colleague, teacher, professor, parents, significant others, all of them said, “Sky’s the limit for Walt. He can write his ticket.” So why isn’t he working for a pharmaceutical company? Why isn’t he making six figures? Why not? And Vince didn’t answer that. “We might explore that,” he said. But ultimately I had to figure that out for myself.

And I thought, “teacher.” That’s the interesting thing. I don’t know whether it was subliminal or intentional. Vince didn’t give me an answer either way. But Walter White became a teacher. It’s a profession that’s shielded from criticism. It’s respectable and honorable. But he’s hiding out. He chose teaching so he wouldn’t get ridiculed. If he’d said, “I’m going to buy a diner,” someone would have responded, “What do you know about a diner? What are you doing? You should go work in a laboratory or something.” To me, it was very specific how and why Walt chose his profession.

Albuquerque wasn’t the original setting of Breaking Bad. New Mexico was chosen for financial reasons. How has this place contributed to the show?

GILLIGAN: You hear it said often with movies and television: “the setting has become a character all its own.” And I never really understood that until I did Breaking Bad here in Albuquerque.

I wrote the pilot of Breaking Bad and set it in Riverside, California, because I thought it would be nice to do a TV show not far from where I live. I could be in the writer’s room and then get in the car and go visit the set, then sleep in my own bed at night. But early on, Sony, our studio, came to me and offered the thought that we shoot in New Mexico instead. When I said, “Why?” they said, “Because New Mexico is offering this 25 percent rebate to productions that occur inside its borders. And 25 percent back in our collective pockets, figuratively speaking, will go a long way toward getting you the things you want to put on screen.” It’s a wonderful incentive and it’s the reason we shoot here.

CRANSTON: We came here for financial reasons. This is a very risky endeavor. Our studio, Sony, was taking on a big risk. They have negative financing every week. They’re losing money. They’re taking a gamble that they’re going to be able to package and sell foreign and sell some sort of package to domestic and make their money back. If they can. It’s not a guarantee. And so the only reason that we’re on the air is because we’re able to take advantage of that 25 percent tax break. We would not have been greenlit. The financials would not have worked out.

It’s amazing to me. It seems like the show could not take place anywhere else.

CRANSTON: Well it certainly has influenced the show. All the Hispanic characters, the DEA, the border stuff. All that stuff is ripe.

GILLIGAN: I’m so glad that that rebate got us here. Albuquerque is a great town. It’s very cinematic looking. It’s fresh. It feels like virgin territory. When you point a camera somewhere around here, chances are you haven’t seen it on TV or in a movie. There’s a lot of virgin powder here, versus in Southern California. You can’t swing a camera without photographing a place that hasn’t been photographed 1,000 times before. I love the freshness that Albuquerque gives our show. I love the desert landscapes, the Sandia mountains in so many of our shots. I love the Old West meets modern West feel of this city. And I love these wonderful fat cumulus clouds that we get in the sky. You so seldom get the kind of cloud formations in Southern California that you get out here, and that’s become a big part of the look of our show.

You mentioned Old West meets modern West. I wonder if in any sense you see Breaking Bad as a modern western, and how.

GILLIGAN: I absolutely see Breaking Bad as a modern western. In that sense, my thinking about the show has evolved a bit since the pilot. When we were shooting the pilot, I wasn’t as familiar with Albuquerque or New Mexico. I hadn’t spent as much time out here. That was before I actually bought a condo out here. So I was thinking in terms of the French Connection. That was a big visual inspiration. I love the French Connection, period. It’s just one of the great movies. It feels as fresh and new today as it did 40-some years ago, when it first came out. It feels timeless to me in a way that most movies don’t. It doesn’t feel dated. And I was definitely riffing on the look of that movie, the news cameraman feel of that movie, as if it was shot hand-held without the aid of tripods, and yet a steady hand-held, the cameraman holding the camera as steady as they humanly could hold them. I love that feel. I definitely paid homage to that movie in the way that we shot the pilot episode.

But the more I’ve gotten to know Albuquerque since that first episode, the more I’ve begun to think in terms of Westerns, which I also love immensely. I love John Ford Westerns, Budd Boetticher Westerns--we actually named a character Gale Boetticher, after Budd Boetticher, who was a wonderful, real-life bullfighter, and a director of B-picture Randolph Scott Westerns in the late 1950s. I love Sergio Leone. Once Upon a Time in the West is a great visual inspiration for this show. Just the opening 15 minutes of that movie are so striking and so interesting and just grab you buy the balls when you watch. Very little is said, and I love that kind of storytelling. I like motion pictures. I like telling a story visually. We work hard on our dialogue on the show, and try to make it sound real, try to make it snap, but our favorite moments, my writers and I, are the moments without dialogue when we’re telling the story visually, and Leone was a master of that. So we’re borrowing liberally from him.

Are there thematic echoes of Westerns as well?

GILLIGAN: There are definitely visual echoes to Westerns, but I suppose story-wise you could think of Breaking Bad in Western terms as well: a man alone against the horizon, being tested, testing himself, testing his mettle. There is a lot of talk in Breaking Bad about what it is to be man. I don’t necessarily buy into all of it myself, but it’s fun stuff to write—fun stuff to tell stories about. I think of Westerns in those terms as well. Men and women in the old West were being tested on a daily, hourly basis. To survive in those days you had to be tough.

CRANSTON: Morality tales. Simple morality tales. You see it all the time. You see the bad guys come up and kill the wife of the good guy, and what happens to the good guy? The good guy goes back and seeks revenge. He either succeeds or doesn’t. And he realizes this is not who I am—or he becomes bad.

What I’ve learned about this is that everyone is capable of “breaking bad.” I really believe that now, from playing Walter White. I think every single human being, given the right set of circuitry, could become incredibly dangerous.