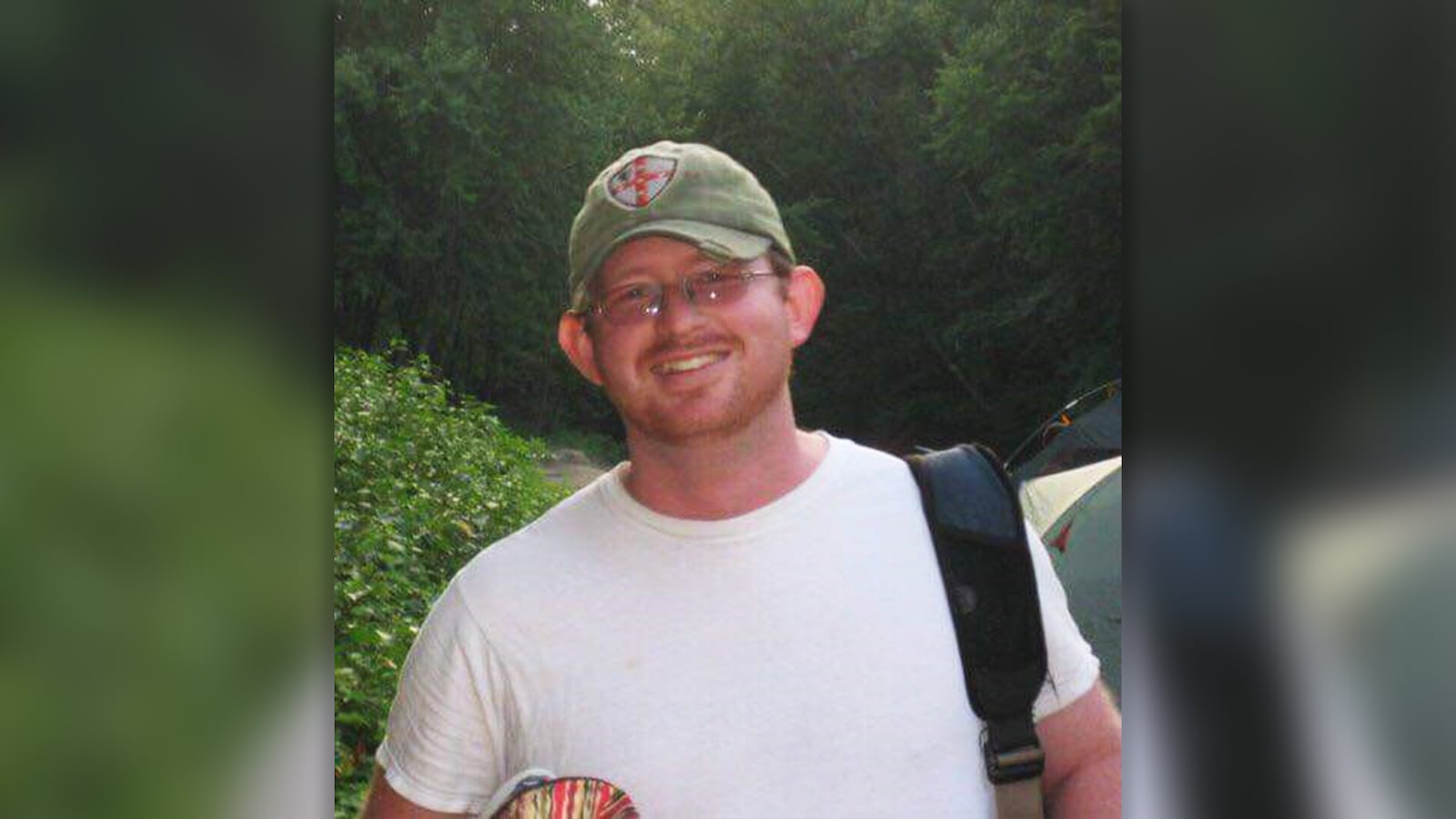

On July 31, 2019, Brian Petersen, a 39-year-old school teacher in Texas, went on the gay dating app Grindr and struck up a conversation with a man whose profile name was “Fresh Meat.”

He asked how the man’s week was going and if he was “looking for something tonight,” according to a transcript of the chat obtained by The Daily Beast. “You into younger boys,” the man replied, apparently posing the question.

When Petersen asked for the man’s age, he said “under 18.” Petersen suggested there was “wriggle room”: In Texas, the age of consent is 17.

But after repeated questioning from Petersen about his age, “Fresh Meat” said he was a 14-year-old named Jason. Petersen asked what school he went to, his sexual experience, and if he could “take it.”

The conversation soon turned toward a planned meeting the next day.

Hours before the encounter, Petersen became nervous and first asked for a voice message. After receiving it, he said the voice was “not what I was expecting.”

Later that day, driving around in circles at a parking lot where the two were supposed to meet, Petersen learned he was speaking neither to a teenager nor a potential romantic partner. Instead, it was a cop: 41-year-old Conroe Police Detective Darrick Dunn, who arrested Petersen for online solicitation of a minor.

The case quickly turned tragic. Less than 48 hours after bonding out of jail, Petersen died by suicide. But the teacher left behind his own version of events, one his family is now using to point the finger at what they describe as overzealous law enforcement.

In a note penned before his death, Petersen claimed he always knew he was talking to an adult due to a dated photograph shared by Dunn, inconsistent details about what school the boy allegedly went to and, most tellingly, he claimed, the voice memo. Although Dunn admitted to sending it, the memo was never stored as evidence—something Petersen’s family and their attorney say would have exonerated Petersen.

“It was almost adorable how funny the message was as you pretended to be a 14-year-old white boy. You were, to me, a guy my age role-playing as a younger guy,” Petersen wrote about the memo, directly addressing Dunn, who is Black.

He said he’d always supported law enforcement’s efforts to catch predators in stings—until he realized they were not always targeted operations to catch men explicitly hunting and soliciting minors. Instead, he argued, they sometimes became “dragnets” that could ensnare men with no history of such desires or crimes.

That he might ultimately beat his charge in a courtroom was “irrelevant,” the junior-high teacher wrote. “This is the type of accusation that destroys a career and a life.”

Petersen’s criticism has been taken up by his family, who recently filed a federal lawsuit against the Conroe Police Department. They told The Daily Beast they want to clear his name, and bring needed scrutiny to online-solicitation arrests they say can be rushed because of society’s unanimous disdain for sex crimes against minors.

“Brian wanted us to ensure that this didn’t happen to other people,” Douglas Petersen, Brian’s father, told The Daily Beast. “He shouldn’t have been charged with a crime, he wasn’t a criminal.”

Kelly Strader, a law professor at Southwestern Law School in California who has studied sting operations against gay men across the country, agreed with Petersen’s family after reviewing the Grindr transcript and the other evidence against Petersen.

Although he admitted Petersen may have kept the conversation going longer than he should have, Strader said he didn’t understand why police were targeting him in the first place. “Had people complained? Had parents complained?” he said. “What was the basis for this? Or was it simply the police saying, ‘OK, let’s go out and grab some gay guys?’”

Strader said his research has shown sting operations like the one against Petersen often have the potential to ensnare men who are not particularly dangerous or posing harm—at least prior to the operation in question.

“Sting operations are going after people kind of at random,” he said. He wondered why the Conroe Police Department would spend their resources going after Petersen without any knowledge of prior acts or accusations. “Evidence. A tip. Something,” he said. “From what I’ve read about this case, there was nothing like that. To me, that’s what is heartbreaking.”

Despite the fact that Strader said he believes the charges against Petersen would have eventually been dropped for lack of corroborating evidence, he said that suicide based on accusations alone is, unfortunately, not uncommon. Perhaps one of the most publicized deaths also occurred in Texas, when Louis Conradt, a district attorney, killed himself as police and a camera crew tried to serve him with an arrest warrant for allegedly soliciting sex from an undercover detective posing as a minor.

Conradt’s arrest was to be part of the famed To Catch a Predator television series. The series was canceled shortly after his death, and the man’s family later settled a lawsuit with NBC.

“There are lots of reports of suicides after arrests during sting operations,” Strader explained, noting that many men caught up in sting operations are not openly gay and feel immense shame after their arrest.

But even as former prosecutors briefed on Petersen’s case acknowledged grey areas, they also said law enforcement was in a tough spot to let someone go once they continued speaking with someone representing themself as a child.

Given that Petersen was a teacher, Christopher Macchiaroli, a former assistant U.S. attorney who now works as a criminal defense lawyer in Washington, D.C., said, the scrutiny has to be even higher.

“What are you waiting for before you have enough that you can say, ‘You know what, we have to arrest this guy?’” he said.

The Conroe Police Department declined to comment for this story. Detective Dunn did not respond to a request for comment.

Petersen, who was born and raised in California, moved to Texas to continue his career in teaching—something his brother, Chad, said he’d always had an interest in. Chad Petersen told The Daily Beast his brother worked his way up from a teacher’s aide and substitute to a junior-high school history teacher in Conroe. Just before his death, he’d been getting ready to start a job as a high school A.P. history teacher, which Petersen’s brother said he called his “dream job.”

After the arrest, his brother said, “everything came crashing down.”

According to his family, Petersen was never arrested or disciplined for any crimes or other misconduct. The Conroe Independent School District, where Petersen taught, did not respond to a request for any records of conduct issues or discipline, and a criminal-records search by The Daily Beast did not turn up any previous charges before the man’s August 2019 arrest.

Although Petersen’s phone, computers, and home were searched after his arrest, no further evidence of criminal activity was reported, according to Conroe Police records obtained by The Daily Beast. The Montgomery County District Attorney’s Office, who would have prosecuted Petersen’s case, also did not respond to a request for comment.

Chad Petersen said the last time he spoke to his brother was the day before his death, because his own son had just been born. He recalled Petersen expressing his congratulations and then oddly remaining silent in the coming days, not returning calls and messages from him or his parents.

It wasn’t until Petersen’s parents flew to Texas and OK’ed police entry into his home that they discovered him dead. A medical examiner ruled it a suicide.

Chad Petersen said they couldn’t make sense of the charge until they heard Petersen’s side of the story in the note left before his death. Although some in the family suspected he was gay, his brother said, Petersen had never formally come out to them.

“You will likely hear a terrible thing about me; namely that I was arrested for online solicitation of a minor,” Petersen started the note. “Even writing that makes me have to pause.”

The note goes on to say that Petersen was active on Grindr, and mainly hooked up with guys who were into “dad” types. He said he’d also met men who enjoyed role-playing as younger men, but that he never had an interest in minors. He criticized law enforcement for being bad at pretending to be teens, and said he never believed he was going to meet a teen the day he was arrested. Instead, he claimed, he figured he was going to meet “someone with an ageplay desire who was probably a Black man my age, as I have done a few times before.”

Strader said “age-play” or role-playing as younger or older partners is common in subsets of the gay community, and is often related to sexual fantasies, not criminal activity. He said defendants in sting operations often claim they were driven by fantasies and that they never had intentions of having sex with a real minor—though it’s a claim most juries don’t buy.

Douglas Petersen said that after reading his son’s note and reviewing the chat on Grindr, he believed Dunn unfairly initiated the conversation around underage sexual activity. He also argued his son initially believed he was messaging someone who was 18 or older, as users are supposed to be on Grindr.

“Dunn was out there trolling,” Petersen said. “Brian was responding to that.”

After subsequently suggesting to Petersen he was under 18 but not yet indicating he was 14, Dunn asked Petersen again in the chat if he was into “younger boys.” Petersen wrote back, “I’m into guys that are interesting. I’m not particularly into younger guys, but I don’t write them off either.”

After Dunn sent Petersen a decoy picture of himself showing a white, smiling teen, Petersen wrote, “How old though?” Dunn responded, “Well I’m young just letting you know.. but I’m fun and cool.”

But Petersen pressed for an age. “How old? You look fun and cool. I just need info to make a choice.” The two went back and forth, discussing a possible meeting, but Petersen continued to ask for an age first.

It was at this point that Dunn wrote that he was 14 and Petersen began to question him about his school, what would happen if they were to see each other in public, and his sexual experience.

Barbara Martinez, a former chief of the special prosecutions section at the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida who supervised cases like Petersen’s for over a decade, said the totality of the case against him did not sound like a great prosecution. She specifically cited the lack of explicit interest in minors, and the absence of hoards of photos and videos typically found in other cases.

Still, she said, she was struck by the fact that Petersen continued to engage with Dunn after he reported himself to be 14. “We see many people who, as soon as they hear the age, they’re like, ‘I’m out’,” she said.

Randall Lee Kallinen, an attorney representing Petersen’s family, said he believes Petersen asking questions about Dunn’s school, casting doubt on the places where the cop reported to live due to his knowledge of school districts, and his request and response to the voice memo all point to his not actually believing Dunn was a child.

This even if he never explicitly said so in the chat.

The attorney also noted that the 13-second voice memo Dunn sent to Petersen was never retained as evidence, which he argued would likely exonerate Petersen if the voice clearly sounded like a grown man.

For her part, Martinez, the former prosecutor, said a common strategy in such cases is to give suspects chances to walk away from the conversation or potential meeting as a way to convince a jury the defendant was set on engaging with a minor.

A review of the Grindr chat between Petersen and Dunn shows that, near the planned meeting time on Aug. 1, 2019, Dunn told Petersen he was “nervous” because Petersen was being “secretive” and not revealing information about himself. Petersen did not press the meeting and asked multiple times if they should call it off. At one point, he expressed his own anxiety, writing “this is new for me” because, he said, he generally only met men over 25.

“I’m likely about as nervous as you are,” he wrote. When Dunn asked what they would do when they met, Petersen did not mention sex or physical activity. “We talk for a bit. I drop you back off. Then we talk on here to see if we want to continue anything today,” he wrote.

Chad Petersen said he supported sting operations and law enforcement going after men who prey on minors. But he said it was clear to him that his brother was not one of those men.

“This was wrong,” he said.

If you or a loved one are struggling with suicidal thoughts, please reach out to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.