Hip-hop is no longer a stranger to Broadway. It is reinventing the form and language, the substance and soul, of American musical theater in ways that are raw and refreshingly young, but that also remind audiences of what made Broadway Broadway a century ago: its edge; its ever-urgent commitment to spontaneity and innovation; its central place in entertaining us while also unveiling social and economic realities of the various races and classes of people occupying the most populous city in our country.

American theater at its finest has embraced a fearless commitment to staging (and therefore trusting audiences to confront) the sounds, struggles, and stories of everyday people wrestling with devils and dreams that come with life upon these shores, bringing these to life on stage. The ticket price on Broadway may be set at the insider’s rate, but the stage itself, at its best, has always made a place for the outsider forcing her or his way into public discourse and bearing witness to what is so easily repressed or ignored about the realities of life on the street.

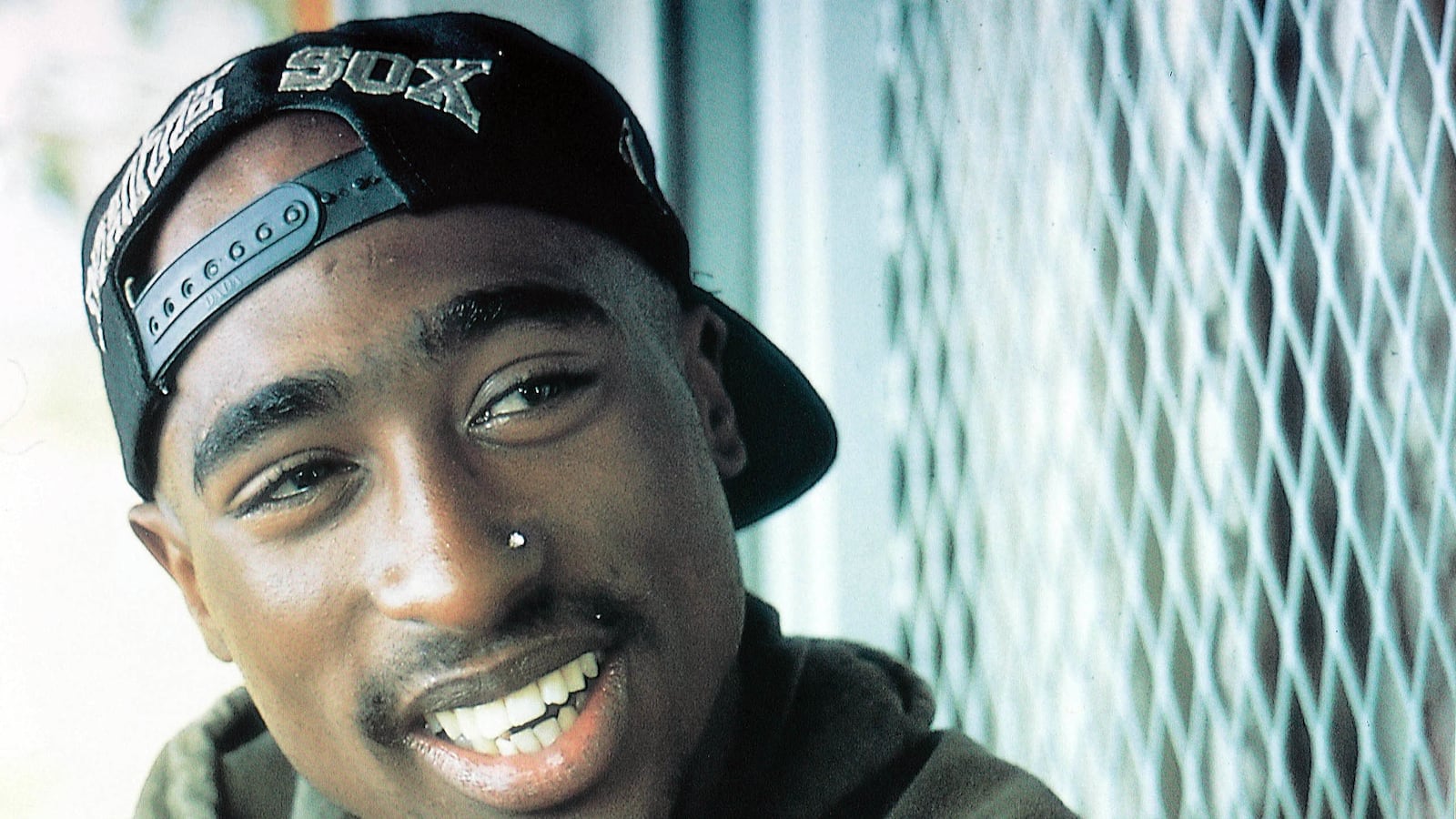

For hip-hop, the door was kicked in—in a major way—by Lin-Manuel Miranda’s brilliantly funny and touching immigrants’ tale, In the Heights, which took home four Tony Awards in 2008. Never before had Times Square seemed so close to the barrio of Washington Heights, even though they’d long shared the same subway line. Now, Holler If Ya Hear Me expands on that legacy by exploring and interpreting the lyrics of the late poet, rapper, and actor Tupac Shakur, aka 2Pac/Makaveli, born in East Harlem in 1971, the year Ben Vereen rocked Broadway in Jesus Christ Superstar and Charles Rangel won his first term in Congress. It does so with the help of playwright Todd Kreidler, one-time protégé of August Wilson, perhaps the most influential African-American dramatist of the last half-century, whose plays Fences (1985) and The Piano Lesson (1990) earned Pulitzer Prizes when Tupac was still making the transition from school to life as a roadie and dancer for the Oakland-based hip-hop group Digital Underground.

In Holler, Kreidler spreads Tupac’s lyrics among different characters who deliver Tupac’s words as they reminisce about Tupac’s place in the soundtrack of their lives. As advertised, Holler is not autobiographical in the same way that the works of Rodgers and Hammerstein are not autobiographical. The characters, like MCs, spit Tupac’s lyrics about the joy and pain, the love and injustice, that he experienced in his all-too-short life—and which they are re-experiencing in their lives on the stage.

Kenny Leon, the director of Holler If Ya Hear Me, considers Tupac to be a great American artist who “belongs in the army of writers with August Wilson and Shakespeare even.” Shakur would appreciate that since he devoured Shakespeare as a high school student and related to works like Romeo and Juliet and Macbeth as though they had been set in the New York, Baltimore, and California of his youth. (Shakur also starred in an early production of Raisin in the Sun at the Apollo in the 1980s, the same play whose revival on Broadway this year with Denzel Washington earned Leon a Tony Award.)

When August Wilson introduced his rich interpretation of the black experience to Broadway, he did so through his epic theater project that reviewed 20th-century African-American history. The plays, each set in a successive decade through the 20th century, seek to chronicle the full historical range of the African-American experience. To an unprecedented degree on the stage, Wilson explored the complex dimensions of black humanity, focusing on the psychological, economic, political, social and cultural consequences of life under segregation—of life “within the Veil,” as W.E.B. Du Bois famously put it.

Wilson took as his settings black working-class neighborhoods and the characters who lived in them. And he viewed his characters not only through a social lens, but also through their peculiar uses of language, humor, and improvisatory creativity, values and characteristics that have long defined and sustained black culture. Wilson’s ear seems to have been constantly attuned to the idioms voiced in church, juke joints, and barbershops, in restaurants and bus stations, on the street and behind closed doors, listening to the way actual black human beings “spoke” the way they lived, loved, and died, recording their vernaculars as they evolved over the course of a century. Wilson’s is a remarkable achievement.

Tupac Shakur shared Wilson’s belief in the power of art, the dynamics of performance, and formal power of spoken language to embody consciousness and inspire social change. In Holler If Ya Hear Me, we are returned to Wilson’s richly textured neighborhoods. But, Holler literally flips Wilson’s scripts, as it were, by depicting the experiences of youth who are the descendents, the grandchildren, of Wilson’s generations, descendants who remain in those same neighborhoods, “trapped in a living hell,” as Tupac rapped on his 1991 debut album, 2Pacalypse Now. Then and now, as the lyric goes, “they can’t keep the black man down.” At least not all of them.

At times, it’s as if Holler’s protagonists are reinterpreting Wilson’s 10-play-10-decade chronicle through a hip-hop interpretive frame, asking themselves the same question that Nas poses: “Whose world is this?” Tupac himself ventured a rather eloquent answer in his composition, “Me Against the World.”

With all this extra stressingThe question I wonder is after death,After my last breathWhen will I finally get to rest through this suppression?They punish the people that's asking questionsAnd those that possess, steal from the ones without possessionsThe message I stress: to make it stop study your lessonsDon't settle for less—even the genius asks his questionsBe grateful for blessingsDon't ever change, keep your essenceThe power is in the people and politics we addressAlways do your best, don't let the pressure make you panicAnd when you get stranded, and things don't go the way you planned itDreaming of riches, in a position of making a differencePoliticians and hypocrites, they don't wanna listenIf I'm insane, it's the fame made a brother changeIt wasn't nothing like the gameIt's just me against the world

Holler takes place in a Midwestern neighborhood much like those of Pittsburgh and Chicago that Wilson introduced to Broadway in 1981. These are the same neighborhoods and blocks housing the descendants of the characters from Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, Two Trains Running, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, Fences, The Piano Lesson, Seven Guitars, King Hedley, Jitney, Gem of the Ocean, and Radio Gulf.

Wilson’s medium was the blues. In fact, as he admitted in an interview with Bill Moyers in 1988, Wilson found his inspiration as a writer digging through five-cent records that he bought at the St. Vincent de Paul store; one, Bessie Smith’s “Nobody in Town Can Bake a Sweet Jelly Roll Like Mine,” he listened to “22 straight times,” so “stunned” was he “by its beauty” and, more importantly, by the way it talked “directly” to him. Like the best drama, the revelatory power of the blues caused Wilson to look at the people in his neighborhood differently; to see “dignity” and “nobility” he had missed before in the lives of the people around him, through the filter of the blues. From that epiphany flowed Wilson’s determination to elevate black working-class experience to high art.

Similarly, hip-hop continues to influence how experiences of black life are written and performed for the stage. Tupac discussed this in terms of legacy in an interview he gave while recording an ultimately unreleased Christmas song in 1992. Unlike those born in “the inner city” (meaning “the suburbs,” he joked), those in “the outer city,” where he came from, had no “empires” to inherit, “no heirlooms” or “family crests.” Instead, they had to build their empires through “culture,” “dignity,” and “determination,” through “music.” “Instead of me fulfilling my prophecy,” he said, “I have to start one,” and that was a lot of pressure.

It was a truth as old as the slave spirituals, and, miraculously, over time, black culture became American culture exportable to the world. By the early decades of the 20th century, Broadway legends such as George Gershwin, to take just one example, couldn’t get enough of it, and imitated and revised it to create their own art forms, which some blacks criticized as “watered down” versions of the originals. Hip-hop signifies on this tradition, repeating and revising riffs and leitmotifs from the black tradition it is extending, but now black popular culture is the lingua franca of post-modern American culture itself.

Where some hear hardness in hip-hop, Tupac heard transformation, evolution. Where the generations of black men and women about whom Wilson wrote had “asked” to be let in the door of American prosperity, and ended up “dead and in jail,” Tupac’s generation, his “raps,” he said in a MTV interview, spoke “truth” to the establishment about the frustrations that come with being “hungry” for so long while others eat. Pouring through him, and now onstage at the Palace Theater on Broadway in Holler If Ya Hear Me, was the musicalized poetry of concrete ’hoods, of ganglands and violent cops, of the tragedy of early prison and social (and literal) death, of impoverishment—a poetry of empathy and indictment, exposing and prosecuting the New World for what it had robbed from so many for so long. Listen to Tupac’s raps enough—perhaps “22 times straight” like Wilson had upon discovering Bessie Smith—and you begin to understand—and believe—that that same hard music Shakur wrote and spun couldn’t have been expressed any other way and still be authentic to the lives of black men in “the outer cities” of the 1990s, and today. To us, it is the contemporary sound through which new and old truths explode in syncopated revelation.

“To me,” August Wilson explained to Miles Marshall Lewis of The Believer magazine in November 2004, “hip-hop is what I call the spiritual fist of the culture.” He continued:

That’s proof that the [black] culture’s strong, robust, inventive. That’s not saying we ain’t got some problems. I mean, it’s the way we used to do with some of them lyrics and whatnot… [Laughter] But I look past that and I go, yeah, now we’re here, we’re strong, we’re alive, we’re robust, we’re inventive, and we still doin’ it. That’s proof of that. So, I embrace it.

Wilson embraced hip-hop as a new musical archive that was telling the stories of a new generation of black people in America that were indebted to the music and experiences of black life in the past. In this sense, hip-hop, for all of its post-modern experimentation, is one of the most historically-rooted genres in American history, repeating and revising canonical black musical phrases through quotation, and thereby keeping the tradition alive, dynamic, ever-reinterpreted. The best of Western poetry, as even T.S. Eliot said in “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” does exactly the same thing.

Interestingly, what became Holler If Ya Hear Me originally went to Wilson to write before it passed to Kreidler. In fact, Kreidler remembers the very morning when Wilson learned his young protégé didn’t know Shakur’s music. So, to “remedy the situation immediately,” “Wilson marched him to the huge Virgin Records store in Times Square and bought the 7 million-seller ‘Me Against the World,’ the 1995 recording released while Shakur was in prison.” As Kreidler recently told Sharon Eberson of the Pittsburgh-Post Gazette, “I started to follow [Wilson] to rehearsal [for King Hedley II] and he said, ‘Where are you going?’ You don’t do anything until you listen to that CD. What you’re holding, there’s nothing in life not touched by what he says — love, honor, community … you’re not going to rehearsal until you listen to this.’”

The greatest tragedy of black American life, for Wilson, was the challenge to confront the trauma of the black past in order to live fully in the present. Wilson repeated characters and themes because he believed that trauma was inherited (not genetically, but socially, through one’s immediate environment) so the black community cannot move forward until they confront and transcend even the most painful details of the past. And one arena in which to stage that confrontation—with madness, apathy, family dysfunction, poverty, etc.—is the theater.

In an interview with The Paris Review in 1999, Wilson, when asked to sum up his project, said:

I like all my characters and I’ve always said that I’d like to put them all in the same play—Troy and Boy Willie and Loomis and Sterling and Floyd. I once wrote this short story called ‘The Best Blues Singer in the World,’ and it went like this— ‘The streets that Balboa walked were his own private ocean, and Balboa was drowning.’ End of story. That says it all. Nothing else to say. I’ve been rewriting that same story over and over again. All my plays are rewriting that same story. I’m not sure what it means, other than life is hard.

Tupac told and retold that same “hard” story for his generation, and now he is telling it to us again through the musical Wilson and Kreidler dreamed about the morning they took that trip to the Virgin Records store. John, the lead character in Holler, brilliantly portrayed by Saul Williams, wants even more than Troy Maxson, but is bound to the images, jobs, stereotypes and limited perspectives of an environment that reduce his humanity to what he does for a living or the mistakes that he made in his life. Like Tupac, John wants empathy and understanding. He wants America to look and see, listen and hear and change—now.

In Tupac’s lyrics there is an embrace of the past. But since there was no justice, there is no peace. The main character in Fences is a garbageman and Wilson made everyone in the audience relate to the life of a garbageman. Hip-hop artists are capable of not only relating to the person whose work is a necessity to any community, but they may also give themselves the MC name of Garbage Man to highlight the need for society to come clean and to see our past and our present without ideological blinders on. Tupac tattooed THUGLIFE on his chest. He forced his audience to see his past coded on his body. His black tattooed body was a constant reminder to onlookers that behind socially constructed stereotypes, young black males want real possibilities to thrive. We, the audience, are forced to read the words on Tupac’s body as a threat or as what he argued it meant to him: The Hate U Give Little Infants Fuck Everybody! What a message indeed!

When theater scholar and critic Harry J. Elam Jr. analyzed Wilson’rs plays, he did so in relation to contemporary African-American art, music, culture and history. The soundtrack to African-American life includes its music and its voices, its distinct manner of phrasing, its lexicon of idiomatic expressions. Gospel, the blues, jazz, soul, funk, had the community laughing, crying, fighting the power, praising the Lord, praising Allah, and marveling throughout, quite self-consciously, at the irony of it all. As Kenny Leon says, “We’re touching on something that I think is very important to the world and, just like Tupac talked about in his music and he talked about himself changing the world, I very much think that this musical can change the world.”

Holler doesn’t wince at the honest material and harsh language of hip-hop, nor does it attempt to wink at the audience to assure them that they will not be challenged. Though the story is not autobiographical, it echoes Tupac’s plea that we hear and act rather than passively listen and do nothing. This perspective requires the audience to see beyond the surface angst and understand the collective pain and bewilderment of life in the city that we all share. As its characters join hands with the men and women of all 10 of August Wilson’s plays, Holler also insists that one never give up hope. In fact, the honesty and language of the play allow the audience to experience the raw anger and frustration as well as the belief that if one doesn’t give in, if one “keeps their head up,” life, ultimately, will get better. Consequently, Holler’s job is to tell a story of loss and conflict while maintaining Tupac’s belief that, to quote Dr. King, “the moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends towards justice”...sooner, or later.

Tupac concludes “Me Against the World” with this outro:

That’s rightI know it seem hard sometimes but uhhRemember one thingThrough every dark night, there’s a bright day after thatSo no matter how hard it get, stick your chest outKeep your head up, and handle it

Black music has always had a unique ability to move listeners with complex social and psychological truths; very often, it was the only way black artists could express political feelings across the color line honestly, even if they had to do so in the coded, metaphorical ways of highly sophisticated art. In their own writing, August Wilson and Tupac Shakur were prophets of that truth, in the same way that the novelist Zora Neale Hurston or the poet Langston Hughes had been before them. And it is truth, hard, unvarnished truth, ladies and gentlemen, that has always distinguished the best Broadway musicals from Vaudeville and bubble-gum pop. As Tupac once told BET, he had no interest in being portrayed as a “role model” for his fans, but in being a “real model” for real people, human beings like you and us.