When he was arrested, Thomas Prusik Parkin told detectives that just because he masqueraded as his dead elderly mother for six years did not mean he was channeling the movie Psycho.

“He said he’s not Norman Bates,” reported Brooklyn District Attorney Charles Hynes.

But detectives say that Parkin sounded undeniably Batesian when he insisted to them that it would be wrong to accuse him of impersonating his mother because he had actually become her at the moment of her demise in 2003.

“I held my mother when she was dying and breathed in her last breath, so I am my mother,” Parkin told detectives.

In the trial now nearing conclusion in Brooklyn Supreme Court, 51-year-old Parkin is being presented by the prosecution as a kind of Norman Bates for our time, armed not with a knife, but a pen, seeking not blood, but money. Rather than terrorize a rundown motel, Parkin is accused of dressing up like his dead mom, Irene Prusik, to perpetuate an intricate series of frauds over a six-year period involving a $2.2 million Park Slope brownstone and a $990,000 mortgage, as well as $115,000 in Social Security and other government payments.

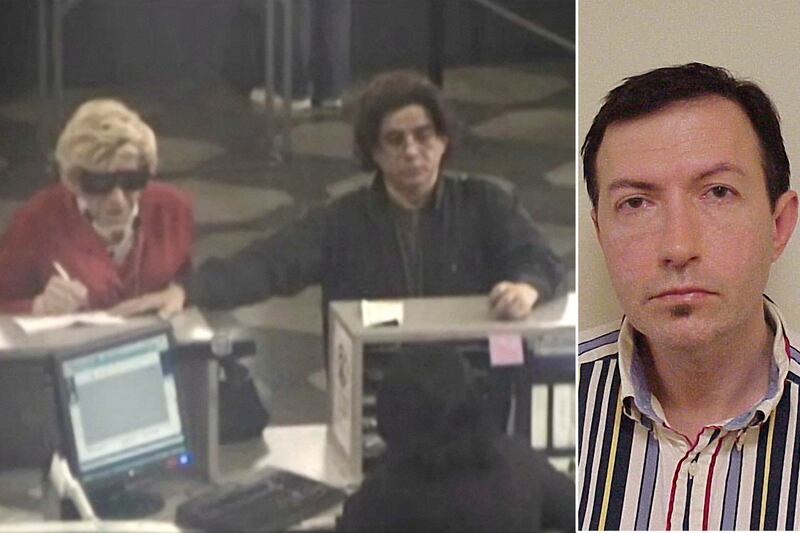

The evidence against him includes a film made not by Alfred Hitchcock, but by investigators with the Brooklyn D.A.’s office using a buttonhole camera. It was screened on Wednesday before jurors, who seemed greatly entertained as they watched a figure in a red top slumped at the end a sofa wearing an obvious blonde wig, lipstick, blackout sunglasses, and an oxygen mask.

“The hands to me did not look like a female’s hands,” D.A. Financial Investigator Vincent Verlezza allowed when asked by the prosecutor after the video was done and the lights came up.

The jurors looked to the defendant’s table, where Parkin sat in a blue shirt, a right hand that looked just like the one in the video clutching a pen and having no difficulty scribbling away on a yellow legal pad. He had the air of someone who is working at not being aware that anyone is staring at him, that wondering eyes in the jury box might be picturing him dressed as his elderly mother.

Actually, as Parkin noted while testifying at a foreclosure proceeding five years ago, Prusik was in fact his adoptive mother. The lawyer back in 2007 asked Parkin if he knew the identity of his biological mother.

“Virginia Prusik Font,” Parkin said.

"Does Virginia Prusik Font have any relationship to Irene Prusik?" the lawyer inquired.

"They're sisters," Parkin said.

"I'm sorry?" the lawyer asked.

"They were sisters."

The lawyer asked Parkin if he knew his biological father.

"Yes, Thomas Parkin,” he replied.

He meant Thomas Parkin Sr.

"What was his relationship, if any, to your adopted mother, Irene Prusik?" the lawyer asked.

"They were boyfriend and girlfriend, common law, living together at one point," the younger Thomas Parkin replied. "From the time I was a baby until I was 10." He said his father had then left his aunt.

"Where did he go?" the lawyer asked.

"The upstairs apartment," Parkin said.

His aunt had by then adopted him. He shuttled between her apartment on the second floor and his father’s apartment on the third floor of 492 Sixth Avenue in pre-yuppie Park Slope in Brooklyn. This is a brownstone his maternal grandmother had purchased in 1933 and was the birthplace of both his biological and adoptive mothers.

"Sleeping quarters in the second floor, living quarters on the third floor," he said of his childhood routine.

He added that the arrangement continued until his father’s death. His biological mother had also died.

"How is your mother's health currently?" the lawyer asked.

"My adoptive mother?" Parkin asked.

"Yes, Irene Prusik," the lawyer said.

"Fair," Parkin replied. "She had taken a stroke a few years ago ... She can't walk properly. She can't speak."

"You speak with her, correct? You meet with her?"

"She doesn't reply directly, really."

"How do you communicate with her? How does she respond?"

"It's one-sided."

Parkin failed to add that Irene Prusik had been dead since 2003. The omission was no doubt related to what seems to have been one of the more remarkable real-estate maneuvers of all time.

According to New York City property records, it all began in 1997, when Irene Prusik supposedly deeded the brownstone to her adopted son Thomas Parkin. He secured a $212,500 mortgage on the building four months later and is said to have sought to parlay the money into greater riches in real estate. His dreams apparently turned closer to dust than gold, and he fell so far behind on the mortgage payments that the brownstone went into foreclosure.

The proceedings were put on hold when a 2003 lawsuit supposedly filed on Irene Prusik’s behalf against Thomas Parkin contended that she had never deeded the brownstone to her adopted son. The suit was lodged by a supposed biological son named Thomas Prusik and included a document in which she supposedly granted him power of attorney.

There was also an affidavit in which the supposed biological son swore that the adopted son forged Irene Prusik’s signature on the deed. All this led to considerable confusion when an apparently real-life (though ailing) Irene Prusik appeared at a hearing and the judge asked about the biological son.

“Where is Mr. Prusik?” the judge inquired.

“There is no Mr. Prusik,” Irene Prusik said.

The judge pronounced himself confounded.

“All I want to know is how she would give power of attorney to somebody that doesn’t exist and are we are here on a motion for someone that supposedly doesn’t exist?” the judge asked.

Neither the judge nor anybody else seems to have imagined that Parkin might have sought to save the house from foreclosure by filing a suit against himself in his mother’s name, using a fictitious legal stand-in to charge himself with having done what he in fact did.

Parkin may have further figured that the revelation that the stand-in did not exist would so muddy the allegation in the affidavit as to make it all but impossible to charge him with forgery.

At the same time, an apparently real Irene Prusik was here in court to confirm the suit’s contention that she had never handed over the brownstone to her adopted son, Thomas Parkin.

“I really don’t think that this lady comes down here with an oxygen tank and a nurse, unless there is some reason she feels that this deed is not a true deed,” the judge said.

Even so, the judge felt legally constrained to dismiss an action filed by a stand-in who did not seem to exist. The foreclosure went ahead, and a man from Queens named Samir Chopra bought the brownstone from the bank for $660,000 in September 2003.

Irene Prusik died that same month, and Parkin solemnly posed for a snapshot beside the open casket. He is also said to have given the funeral director an incorrect Social Security number for his mother, thereby preventing her death from being logged in the federal database and allegedly allowing him to collect her continuing Social Security benefits.

And death did not prevent the lawsuit Irene Prusik v. Thomas Parkin from being revived and pursued without the nonexistent stand-in. Parkin declined to contest the suit he seems to have in fact filed against himself. The resulting judgment held that Irene Prusik remained “the true and rightful owner,” and that the deed was declared void “in that the plaintff’s signature on said deed is false and a forgery.”

A friend of Thomas Parkin’s named Mhilton Rimolo became a new stand-in with power of attorney, and the brownstone was now mortgaged in Irene Prusik’s name for $938,250. The tale might have ended there had the manifestly legitimate guy who bought the house at a foreclosure sale been more easily deterred. Chopra apparently sensed a flim-flam and continued to press his claim in the courts until he got the sale reconfirmed and Parkin was ordered to vacate the brownstone.

In what seems to have been a remarkably audacious attempt to head off his opponent, Parkin went to the Brooklyn district attorney. He characterized himself and his poor ailing mother as victims of a fraud who were about to be tossed into the street.

“She has the last deed on record,” he told investigators. “She’s the rightful owner.”

Investigators soon began to suspect the truth. They repeatedly asked to meet Parkin’s mother during a series of recorded calls.

“Your mother, you don’t think she’ll be up to talking to us?” Financial Investigator Verlezza inquired during one.

“She doesn’t even know what’s going on,” Parkin said.

Parkin explained that because of his mother’s fragile health he spared her the details of the continuing struggle over the house. “We don’t want to expose her to too much,” Parkin said.

The investigator said at one point that he had seen photos of the mother when she was younger.

“I see she was a model at one time,” the investigator said. “A very pretty woman.”

“Even when she was older,” Parkin said. “Unfortunately, with her stroke … She doesn’t speak as well … She has the oxygen mask.”

The investigator noted that the mother did not seem to be on Medicaid.

“She never wanted Medicaid,” Parkin said. “She was afraid they’d take the house.”

“So she’s not under a physician's care now?” the investigator asked.

“From time to time in New Jersey,” Parkin said, adding that she sometimes took herbs and homeopathic remedies. “I think she did acupuncture.”

“How old is your mother?” the investigator inquired.

“She’ll be 77 next month, 76 now,” Parkin said.

A month later, the investigators were still pressing to meet the mother.

“She’s in New Jersey now,” Parkin said. “It’s her birthday.”

“Did you have a party?” the investigator asked.

“We had a little bit of a celebration in New Jersey,” Parkin said. “Her sister’s buried over there.” The sister being Parkin's biological mother. Parkin continued, “And she wanted to go see her. It was a little solemn, to tell you the truth.”

The investigators said they only needed the mother to confirm that she had accorded Rimolo the power of attorney. Parkin finally relented and set a time for the investigators to come by the brownstone and speak with her. Verlezza and a detective arrived with the buttonhole camera and were welcomed by Rimolo, who led them into a dark room on the first floor.

“The light is off,” Rimolo said. “She just had cataract surgery.”

The camera captured the mute figure slumped on the sofa who would later draw laughs from the jury. An oxygen compressor was humming. Rimolo told the investigators that Parkin was unable to be there because he had to be in court.

“Oh, that’s where he is, he’s in court,” Verlezza said.

Rimolo introduced the figure on the couch to Verlezza. “Irene this is Vinnie … the guy from the D.A.’s office,” Rimolo said.

“Hi, how are you?” Verlezza said. “Irene, you can understand me, Irene? You can speak to me? She can write?”

Rimolo said, “Irene, they are asking you questions …You need to write down something.”

Verlezza explained to Rimolo, “We have to make certain she does own the place, she's really the person.”

The investigator then addressed the figure again.

“Basically, Irene, I have to ask you if this power of attorney is still a good power of attorney. I don’t know if you can indicate that either with your eyes or nod your head. If it’s easier, just nod your head, that’s fine.”

A home health-care aide who had been hired just for the day assisted in placing a pen in the figure’s hand. The aide then read aloud the single word the figure inscribed on a sheet of paper.

“Yes.”

“Okay, she wrote yes,” the investigator said.

The investigator then produced a document and said it was a statement of witness attesting that the power of attorney is still in effect. “I want, Irene, if you could sign this," the investigator said.

Rimolo leaned closer to the figure.

“Irene, remember you gave me the power of attorney,” Rimolo said. “Sign again that I have the right to continue to be your attorney.”

The figure signed the paper that would be used as evidence against Rimolo and Parkin after their arrest. Rimolo pleaded guilty to fraud charges and was sentenced to a one-to-three-year term. He asked the judge if that meant he had to go to prison upstate.

“Yes, that's the way it works,” the judge said.

Parkin faced a much stiffer term of 25 years and stuck to his not-guilty plea. He is presently on trial. Along with the buttonhole video the jurors watched, there was surveillance-camera footage from the Department of Motor Vehicles office in Coney Island showing the figure from the couch renewing Irene Prusik's license, apparently in an effort bolster the fiction that she was alive.

Along with the pen instead of the knife, a big difference between Thomas Parkin and Norman Bates on screen is that when the jurors saw the figure in the wig, they just smiled and shook their heads.

The trial continues this week.