Late in All the Way, Lyndon B. Johnson (Bryan Cranston)—celebrating his reelection to the Oval Office after a grueling 1964 campaign against conservative Republican challenger Barry Goldwater—intones to himself, “You’re goddamn right it’s my party. And I had to drag it into the light kicking and screaming every inch of the way. Cuz this is how new things are born.” That belief, in the painful, bloody process of creating something great, has by this point been shaped by his own experience losing his first three children during delivery with wife Lady Bird Johnson (Melissa Leo). And it’s been reaffirmed by his struggle to enact the 1964 Civil Rights Act, a contentious piece of legislation whose ratification is the prime subject of Jay Roach’s solid (if a tad stodgy) historical character study.

All the Way is based on Robert Schenkkan’s 2014 play that won Cranston a Best Actor Tony, and one can feel the staginess of its construction throughout, from its confined interior dramatic spaces to its clean narrative bifurcation—with its first half centered on Johnson’s efforts to gain votes for the landmark law, and the second focused on his attempts to maintain support from angry racist Southerners in the lead-up to the ’64 Democratic National Convention. That’s also true with regard to Cranston’s performance, which has an outsized blustery showiness that seems pitched not only to TV audiences, but to the back rows of the Broadway theater.

Nonetheless, one can rarely sense that Cranston is acting, so fully does he inhabit his exceedingly well-written role. As imagined by Schenkkan (who penned this self-adaptation), Johnson is a man who—thrust unwittingly into the spotlight by the sudden assassination of JFK, whose blood-stained Texas motorcade car is the action’s somber opening image—is simultaneously noble, brave, self-serving, insecure, and nasty. Convinced that the Civil Rights Act is “the right thing to do,” even as he guts it of its voting-rights component for shrewd tactical reasons (much to the chagrin of Anthony Mackie’s Martin Luther King Jr. and his comrades), this Johnson is both a bleeding-heart believer in equality under the law, and a self-interested politician determined to retain power at all costs.

As glimpsed in his interactions with others, including his loyal wife, he’s also a callous prick prone to terrifying verbal abuse.

When Johnson tries to convince a fellow Georgian Democrat to keep Southern allies from abandoning the ‘64 Atlantic City, New Jersey, convention—a spat caused by Johnson and King’s decision to send two delegates to the event from the newly formed Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP)—Johnson segues on a dime between uplifting orator and belligerent bully. After a particular bit of vitriolic censure from her husband, Leo’s Lady Bird says of him, “He’s hard on everybody, especially himself,” and the sentiment comes across as a feeble apology from a psychologically battered wife, as well as true, since Johnson routinely expresses paranoia, doubt, and outright disgust at himself over his dubious ability to accomplish his groundbreaking goals.

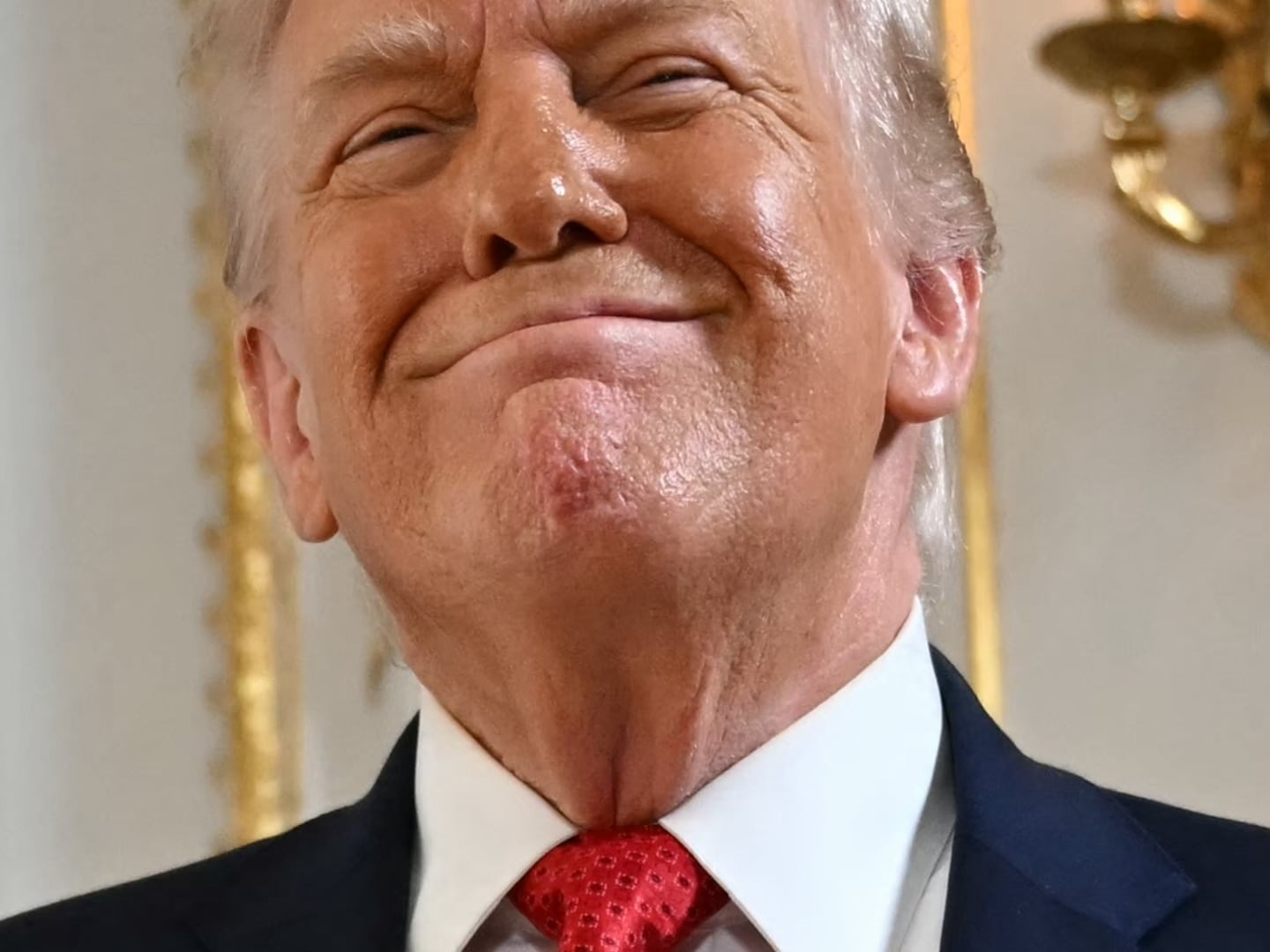

Cranston brings Johnson to life with a bevy of Southern-twanged Big Statements (ex: “There’s no place for ‘nice’ in a knife fight”) as his commander-in-chief berates his eventual VP Hubert Humphrey (Bradley Whitford), spars with beloved mentor-turned-Civil Rights opponent Senator Richard Russell, Jr. (Frank Langella), and works closely with advisor Walter Jenkins (Todd Weeks), the last of whom he loves “like a son” and yet abandons when the man’s homosexuality is exposed late in his reelection run. Even without Roach’s grating habit of shooting the proceedings in too-tight close-ups, Cranston delivers a titanic fill-the-screen turn, capturing the man’s bombast and sincerity in equal measure. In the process, he dwarfs his castmates; those that enter into Johnson’s sphere come across as simply well-drawn two-dimensional figures, including J. Edgar Hoover, here embodied by Stephen Root as a pursed-lip, wide-eyed creep whose disgust over King’s supposed moral hypocrisy (a preacher cheating on his wife!) resonates with bitter irony given the FBI bigwig’s own personal secrets.

“Politics is war, period,” states Johnson, yet All the Way is less a portrait of a battle than of an individual leader. As evidenced by climactic cross-cutting between the two men’s speeches, Mackie’s King is meant to function as Johnson’s counterweight equal. The script, however, relegates him—unavoidably—to second fiddle. Mackie doesn’t stress King’s Southern verbal inflections too hard, and he puffs out his chest to suggest the civil rights icon’s physical (and moral) heft. Nonetheless, Schenkkan’s script treats King’s own skirmishes with African-American activists like requisite, albeit complementary—and second-tier—material.

Executive produced by Steven Spielberg, All the Way recalls Lincoln in its depiction of the hostile backroom wheeling and dealing required to push progressive laws—and a nation—forward, and the link between the two works is underlined in the former’s first scene, during which Johnson proclaims, “I’m going to out-Lincoln Lincoln!” Though it presents a captivating look at the nuts and bolts of high-stakes politicking, it suffers in such inevitable comparisons, in part because Roach’s direction is so stifling that the film feels small at the very moments it should be grand. It’s not quite fair to expect Roach (known for Meet the Parents and The Campaign, as well as political works like this, Trumbo and 2012’s Sarah Palin-centric Game Change) to boast Spielberg’s canny way with light, shadow, and framing. Still, his flat visuals and ho-hum staging do much to make All the Way seem like it belongs on the small screen.

Like Lincoln, Roach’s film aims to capture the essence of a world leader at a historically critical juncture. Alas, by occasionally having Johnson speak with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (Bo Foxworth) about the escalating conflict in Vietnam, it merely manages to hint at the less inspiring aspects of the president’s tenure. Given the limited parameters of this project, such a tack makes sense, and yet it also lends All the Way a somewhat blinkered view of its subject, holding him up high while only suggesting the reasons that his legacy—marked by both noble domestic triumphs and more problematic international quagmires—remains so complicated.