ORLANDO—Ten miles from Disneyworld, the lobby of the Omni Orlando Resort was packed with restless kids sporting Mickey and Minnie Mouse ears, their exhausted parents in tow, drying off from splash-arounds in the outdoor pool and lazy river, or heading back inside after a round on the nine-hole pitch and putt.

But just a few escalator rides away, past the gift shops, there was no more fun for kids.

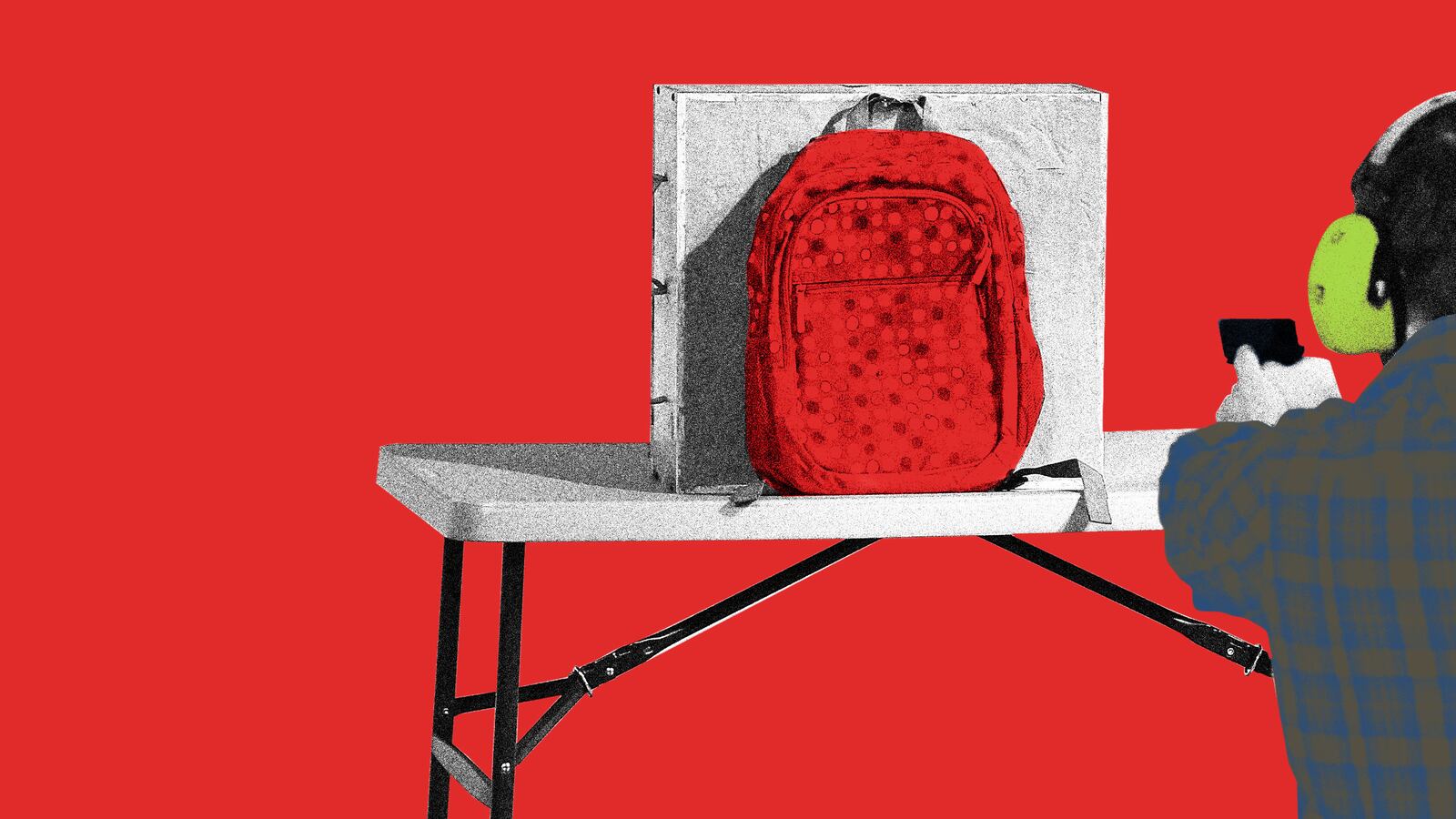

It was the site of last July’s National School Security Conference where education experts, law enforcement officers, and entrepreneurs—“anyone involved in protecting our schools”—mingled among “bulletproof” backpacks, pepper-spray guns and door barricades. There were gunshot-detection systems, one resembling a clunky, oversized Game Boy. There were emergency tourniquets that children would learn to apply to classmates’ limbs after shootings, to stop the bleeding.

The product exhibition was only a part of the five-day professional brainstorm on making schools safe again. School culture formed the other segment of the conference, covering such issues as mental health, threat recognition and active shooter drills. Guests headed to seminar halls for breakout sessions such as “Complete Your Classroom Lockdown” and “Active Survival.”

“The Cynosure Effect” was presented by Steve Webb, a superintendent from Goreville, Illinois and member of the Illinois Terrorism Task Force School Safety Working Group. He had a shaved head, polo shirt tucked into tan slacks and a cellphone holster, which all combined to create the unofficial uniform adhered to by many of the attendees.

He paced up and down the aisle of the ballroom as he his imparted his PowerPoint wisdom, and shared that the three Ts of modern school safety are “terrorism, technology and teaching,” in that order. Shooters in the making suffer from cynosure, or the desire to be the center of attention, he said. They yearn to outdo and become more “Instafamous” than the previous shooter. He blamed social media and video games like FortNite. None of the recent research studies conducted on the topic have shown any correlation between these suggested causes and school shootings. Kids in other countries use social media and play video games, yet do not experience such violence in their places of learning.

He mocked the notion of holding guns responsible, and this was a trend at the show. Some remained neutral, while many balked at the futile notion of gun control. Instead, they pointed fingers at the rise of bullying in the age of Facebook and Instagram.

Brad Jarrett, who’d brought the Game Boy-like gunshot detector, blamed bad parenting.

“I think we’ve lost control of how to raise our kids,” he said, lamenting that parents have put careers first and children second.

“When I was a kid, we used to bring guns in for show and tell,” Jarrett reminisced. “You didn’t think about shooting.”

Safety has become a priority for schools, especially following the Parkland massacre and its subsequent media coverage. But with little federal emphasis on gun control and minimal funding for security, states and districts are left to protect themselves and must spend the scant money on what they deem right for their school networks. Some states allow districts to enact levies to raise revenue specifically for safety, while others must simply rely on competitive grant programs from the government. Whatever the case, funding is scarce.

Many schools are investing in physical hardware. The security sector of the education market is now worth $2.7 billion, up from $2.5 billion in 2015, said Jim Dearing, senior security analyst at IHS Markit. According to a report by the National Center for Educational Statistics, the number of public schools using security cameras increased from 19% in 1999-2000 to 81% in 2015-2016.

The NRA’s School Shield program has encouraged the holistic “hardening” of campuses, through building restrictive barriers like perimeter fencing, reinforcing reception desks with ballistic steel, and re-welding door hinges to prevent tampering.

“Hardening” has been a phrase authorities have used in relation to schools since Parkland. Florida ex-governor Rick Scott of Florida passed a bill that distributed $99 billion for “school hardening” last March. The White House used the phrase on an infosheet to announce steps to ensure schools are secured “just like our airports, stadiums and government buildings.”

On display in one of the conference ballrooms was a bulletproof whiteboard. I met Jim Muth, a representative of the manufacturer, EverWhite. “Teachers are notoriously so brave,” he said. “They’re getting in front of students while a shooter is shooting at them.” The boards aimed to replace teachers as those shields.

The interiors are crammed with Level-III ballistic material rated to stop handgun ammunition and some rifle ammo. (The whiteboards are tested at a firing range.) But they wouldn’t protect against bullets from an AR-15, the weapon used in mass shootings in Parkland, Sandy Hook, Santa Fe, Orlando and Las Vegas.

Priced at up to $2,800 per panel, the boards are on wheels and made with a flexible hinge system. They’re 70 inches high, in line with most doorways. Their center of gravity is such that they’re difficult to tip over. And their exteriors are tailorable—printable with the alphabet, numbers, music staffs or storybook characters—meaning they blend into normal classroom environments.

“It’s about fortifying the school,” Muth said. “We are trying to help teachers teach.”

Some tools target building exteriors, providing additional bubbles of protection. Representing Window Tint Specialists, Steve Fisher insisted that the key to stop the “bad guys” was through lining classroom windows with 3M’s Ultra film. Though not bulletproof, the sheet is made from 60 layers of tiny microfibers, which stiffen to create a Kevlar-like armor.

“The product can be pierced, but you can’t tear it,” Fisher explained. “The harder you push on it, the stronger it is.”

The film’s dark tint would confuse a gunman, and its strength would keep him out for enough time for police to arrive on scene. It works best in tandem with other security measures like metal detectors, providing a multi-layered approach to school safety.

Several attendees said they wouldn’t consider much of the hardware, many for budget reasons. Some were simply skeptical about the efficacy. One of the conference organizers, Sean Burke, said that some of the gadgets aren’t fit for a school environment. Commenting on the bulletproof backpacks, he joked, “I get the picture of Wonder Woman with her magic bracelets.”

The Department of Homeland Security now officially preaches the mantra of run-hide-fight in the event of a shooter on site. When the hide option is exhausted, the only remaining option is to fight, and some of the security gadgets focused on this eventuality.

One was promoted by Kyle Tengwall, the former chief marketing officer of Duck Commander, the merchandise company of Duck Dynasty, the wildly popular reality show about gritty duck hunters in the Louisiana bayou. (He sported a shorter, tidier beard than expected for a Duck Dynasty veteran.)

When I met him for breakfast at the Omni Resort in Orlando, Tengwall recounted how he’d spent much of his career on the “lethal side,” running marketing for Federal Ammunition. That was before he moved to “non-lethal” problem-solving, bringing his marketing savvy to the PepperBall Protect.

That’s a device that shoots “PepperBalls”: small, spherical rounds that resemble paintballs but contain a pepper spray called PAVA. The 12-foot cloud of pepper powder that disperses with a shot is intended to disable a gunman during a school shooting. Before targeting the school market, PepperBall made products that SWAT teams used to control riots, allow hostage extractions and end child-trafficking situations.

At $299 plus a dollar apiece for ammo, the “non-lethal” gun is disguised as a flashlight. Teachers or janitorial staff can first use it as a real flashlight to check school hallways if they hear unusual commotion.

Tengwall allowed me to test the flash-gun on the edge of the resort’s golf course. “Aim low,” he said, “and then go ahead and aim for the face if it becomes more of a lethal encounter.”

It was lightweight and wieldy, and relatively easy to fire. I pointed it toward the well-manicured bushes and slid the safety forward, which activated a red laser to help with aiming. The trigger is a red button that masquerades as the flashlight switch. I pushed it repeatedly, emptying the rounds into the shrubbery. It was hard to imagine the potency as the PepperBalls gently glided off leaves, but Tengwall clarified: “It’s like a human punch. It’s not going to break your skin, but it’s going to get your attention.”

Lethal weapons weren’t beyond discussion, though.

Eight states already have laws explicitly allowing teachers to carry weapons in school; armed security guards on site are even more widespread, with 28 states subscribing to this practice.

Some at the conference believed the solution to guns was more guns, most notably at a seminar titled, “Arming Teachers, What’s the Alternative?”

“Teachers are the first line of defense,” began Jennifer Schiff, a police detective from Clarkston, Georgia. “Parents are expecting to see teachers put themselves in physical danger to protect their children. I certainly hope my grandson’s teacher would. But they need the training and tools to do that.”

That training includes threat detection. If a student is walking unusually stiff-legged, for example, teachers should recognize that’s because he may have a shotgun in his pants.

But most importantly, teachers who are “willing to die for their students” should be trained on how to operate lethal weapons.

Schiff asked her audience why violence should be treated any differently than, say, a peanut allergy or a bee sting. If teachers aren’t doing anything to heal or protect, she reasoned, they’re bordering on negligence.

Schiff broke it all down for me after the seminar: Mass shooting history has shown that, when the police arrive on site, a gunfight between the law and the outlaw is inevitable—so why not start it earlier?

“There’s going to be uninterrupted execution until then,” she said. “And we’ve taught our kids not to fight back.”

Guests reconvened for the farewell meeting Friday morning in the main ballroom, where organizers Sean Burke and Curtis Lavarello made closing comments. They noted some statistics gathered from the week’s attendees. Sixty-five percent of schools now perform active shooter training and 41 percent of schools had said they were prepared for a shooter.

Twenty percent had said they approved of arming personnel, “as long as they’re trained.” Among the strongest arguments against it was the potential for error. “How do you know who’s the bad guy?” They cited past mishaps, including accidental shootings and guns found in bathrooms.

“I own a lot of guns. I believe in the Second Amendment,” Lavarello said. “But I’m not sure how prepared our staff will be.”

Gun control was once again absent from the concluding comments. The directors discussed the vital role of school resource officers and the need for preventative mental health programs.

“Before all the gadgetry comes in,” Lavarello said, “the best thing we can do is know our kids.”

Burke and Lavarello are now taking registrations for the next National School Safety Conference. This July, it’ll take place at in Las Vegas at the Tropicana Hotel. It’s all just minutes away from The Strip’s newest attraction, the off-limits Mandalay Bay hotel room from which 58 people were murdered and 422 shot and injured less than two years ago in the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history.