The indifference of Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin as he kept his knee on the neck of the dying George Floyd translated to fury in the streets. And with that anger rose memories of other deaths and other brutal cops.

One question that accompanies all of it is: How do we separate out the bad cops?

The Minneapolis Police Department has long talked of reform and had instituted a computerized early intervention system that was supposed to identify problem cops. Yet it still kept on the likes of Chauvin and the three other officers who did nothing as Floyd cried, “I can’t breathe” and “Mama!”

But now Minneapolis may have found a way toward reform through technology, a possible key to progress pioneered by a data scientist who was key to President Obama's analytics-driven victory in 2012.

As the campaign’s chief data scientist, Rayid Ghani employed data science, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to help put Obama in the White House. Ghani then went on to the University of Chicago, where he explored ways to apply data for the public good.

In 2015, the Obama administration invited him to join a task force examining ways to improve policing through technology. A large number of police departments—Minneapolis and Seattle among them—had already instituted rudimentary data-based early intervention systems (EIS) that used such triggers as excessive force complaints to flag problematic cops.

“But nobody had any idea if they worked at all,” Ghani told The Daily Beast this week. “Nobody had ever done an evaluation, which was shocking.”

The 42-year-old scientist and his team examined the result that year and found that as many as 80 percent of the officers in a department were being flagged as possible trouble, many without reasonable cause. A considerable number of cops who actually were trouble were not being identified.

And any system built on triggers could only tag officers after they had already done something. “It’s not an early warning, it’s a late warning,” Ghani noted.

He added that every problem cop who transgresses does it for the first time at some point. “A trigger-based system would never, ever catch the first time,” he said.

He and his data crew concluded that the departments would have done just as well tagging officers blindly.

“It was not much better than random,” he said.

The Ghani crew set out to develop an early warning system capable of predicting trouble before it happens, so there would not be a first time. They had tools such as those had employed in the Obama campaign and were becoming ever more advanced.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department (CMPD) in North Carolina was a promising place to start. Many police departments silo their data collection in the various divisions but CMPD was centralized. Data from every division was accessible from a single locus. Even better, the CMPD seemed actually enthusiastic about change.

“Charlotte, they’ve been great,” Ghani said. “They want to do the right thing... They were totally committed: ‘We want to fix this. We don't have a huge set of these issues, but we have some and we want to improve that.’”

The Ghani crew set to work. They started by asking CMPG to collect data over the previous five years. “Assembling every bit of data they could on every police officer,” Ghani said.

More than 1,100 variables were considered. Personal history. Training history. Stops made. Who was stopped and where. How often arrests were made. Who was arrested. At what time? What type of jobs from dispatch? How often was force used? Was it justified? Were there injuries? How many Internal Affairs complaints? How many were substantiated? Assigned outside usual beat? Working a second, off-duty job? And on and on.

Ghani and his crew then acted as if they had gone back in time five years. They took that year’s data and used their divining tools. They compared what they “predicted” from that data with what had actually transpired. How many cops who they “predicted” to be a risk had actually been trouble?

They then did the same with two years of data, then three, then four, finally five, using the results of each run to refine the next as they traveled from the past into the present. They were able to identify variables and combinations of variables that appeared to increase the probability a cop would turn “problematic,” meaning brutal or corrupt. The variables that proved to have some impact on whether a cop became a risk included repeated dispatches to domestic violence cases involving children and to suicide attempts.

“Stress,” Ghani explained.

Complaints were still considered, but only in the context of the rest of the data concerning the particular officer. A number of complaints about a very active cop proved not necessarily to be a determinant of trouble, while a single complaint could be a warning signal for a cop who did little.

And, unlike the trigger system, this new approach was not seen as disciplinary.

“If it is actually early warning, they haven’t done anything yet, so you don't have to do punitive,” Ghani said. “If they haven't done anything yet, you can be much more preventative.”

Ghani allows that the early warning system is hardly perfect, but it is considerably better than random. And even if it were perfect, it would only predict, not prevent.

“That’s the trickier piece,” he said.

The tough question is what to do once an officer has been identified as a risk. “Is it training? Is it counseling? Is it cool-down periods? Is it desk periods?” Ghani asked.

He hopes the next step will be to work with the CMPD on predicting not just which officers are a risk, but also the best remedy. That effort has been delayed because he moved his operation from the University of Chicago to Carnegie Mellon University.

Meanwhile, the CMPD is using the early warning system and employing whatever remedies seem best.

“Each officer is assigned a risk score and ranked from the highest potential risk to lowest,” a CMPD spokesman explained by email to The Daily Beast. “Monthly, the professional standards captain reviews the top 5% (or roughly 100 officers) in great detail. An alert can then be issued for that officer’s chain of command to evaluate and set up a remedial action plan. Field supervisors can also create an alert for any officer if they notice a pattern or sudden change in behavior independent of the computer model.”

The most recent available CMPD internal affairs report says that complaints about officers between 2016 and 2018 declined from 189 to 158, an 18 percent drop. (The complaints for 2020 are likely to include Charlotte’s use of tear gas, flash-bangs, stun grenades, and pepper balls at a protest against Floyd’s death on June 3).

On June 10, the Minneapolis Police Department announced that it is also signing up for the early warning system based on Ghani’s work and marketed by Benchmark Analytics. The apparent failure of the department’s existing early warning system to flag Officer Chauvin has added to criticism of data-driven policing in general.

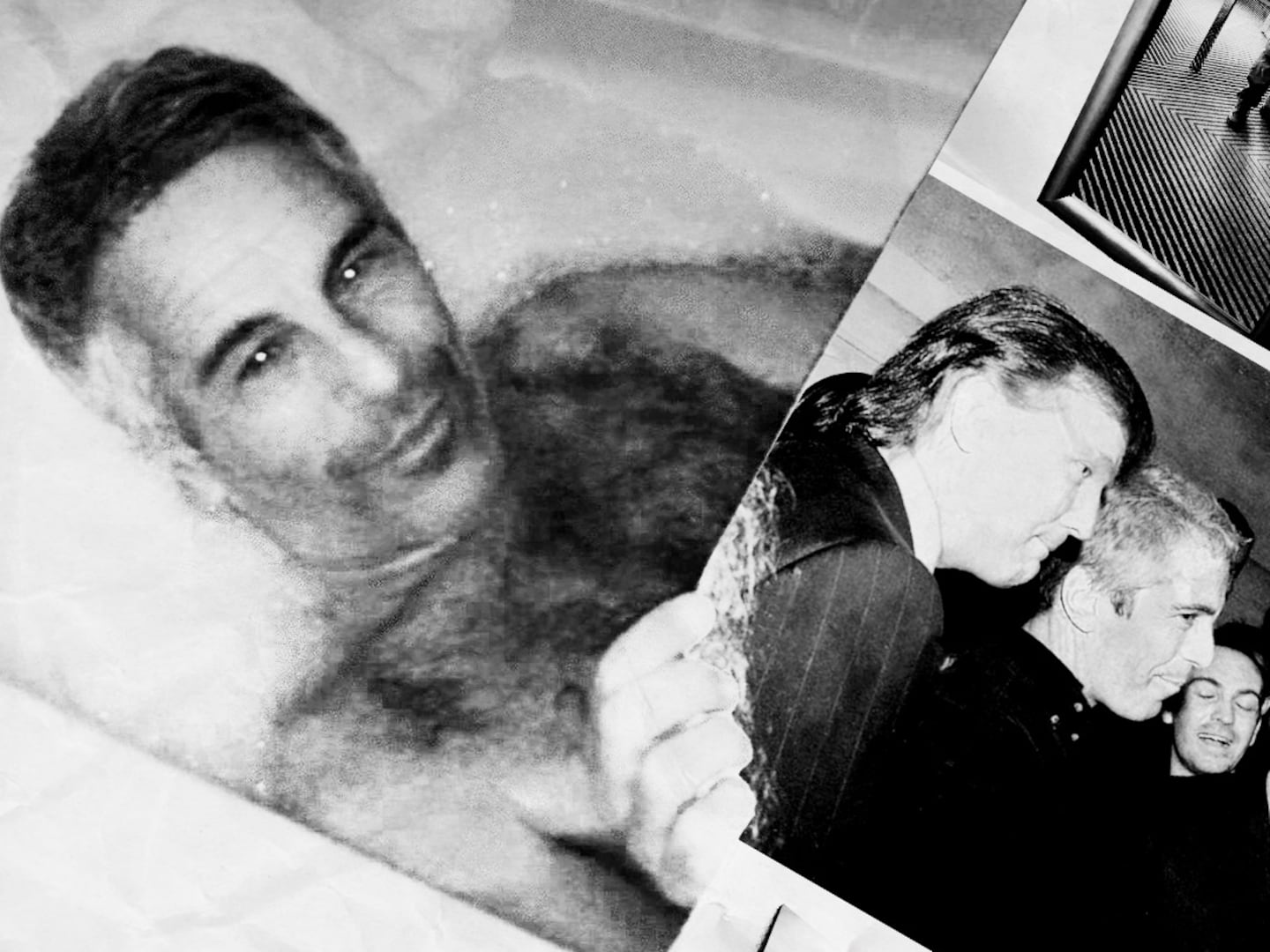

After all, Chauvin was not only a cop but also a training officer, despite racking 18 complaints in 20 years. He had a questionable shooting during a struggle with an unarmed man at the scene of a domestic violence incident. There was a substantiated internal affairs complaint resulting from an August 13, 2007, incident.

“Complainant alleges officer pulled her from her car, pat frisked her and placed her in the rear of the squad car for going 10 mph over the speed limit,” the IAD report in the department database reads.

The report adds that the squad car’s video system and the microphone and the microphone all squad car drivers are required to wear “had been turned off during the course of the stop.” The report says that Chauvin was disciplined for that and for poor judgment.

Any other details are forever unavailable. The reason is spelled out in block letters and assumes particular importance when you consider the department had just signed up for the original early intervention system.

“CASE FILE DESTROYED - LIMITED DATA”

Somebody had a camera on 13 years later, as Chauvin pressed his knee on Floyd’s neck. A dispatcher was able to see the images. She contacted the supervision sergeant.

“I don’t know, you can call me a snitch if you want to…” the dispatcher began.

The very idea that the dispatcher would even consider somebody calling her a snitch in such circumstances suggests something more profoundly wrong than any algorithm can address. And how do you measure risk when four of four officers fail to respond when a dying man repeatedly says, “I can’t breathe!” and “Mama!”

But to look at Derek Chauvin’s personnel file—from his school records to the time he yanked a woman from a car—is to wonder if maybe predictive analytics could have alerted his superiors when common sense failed.

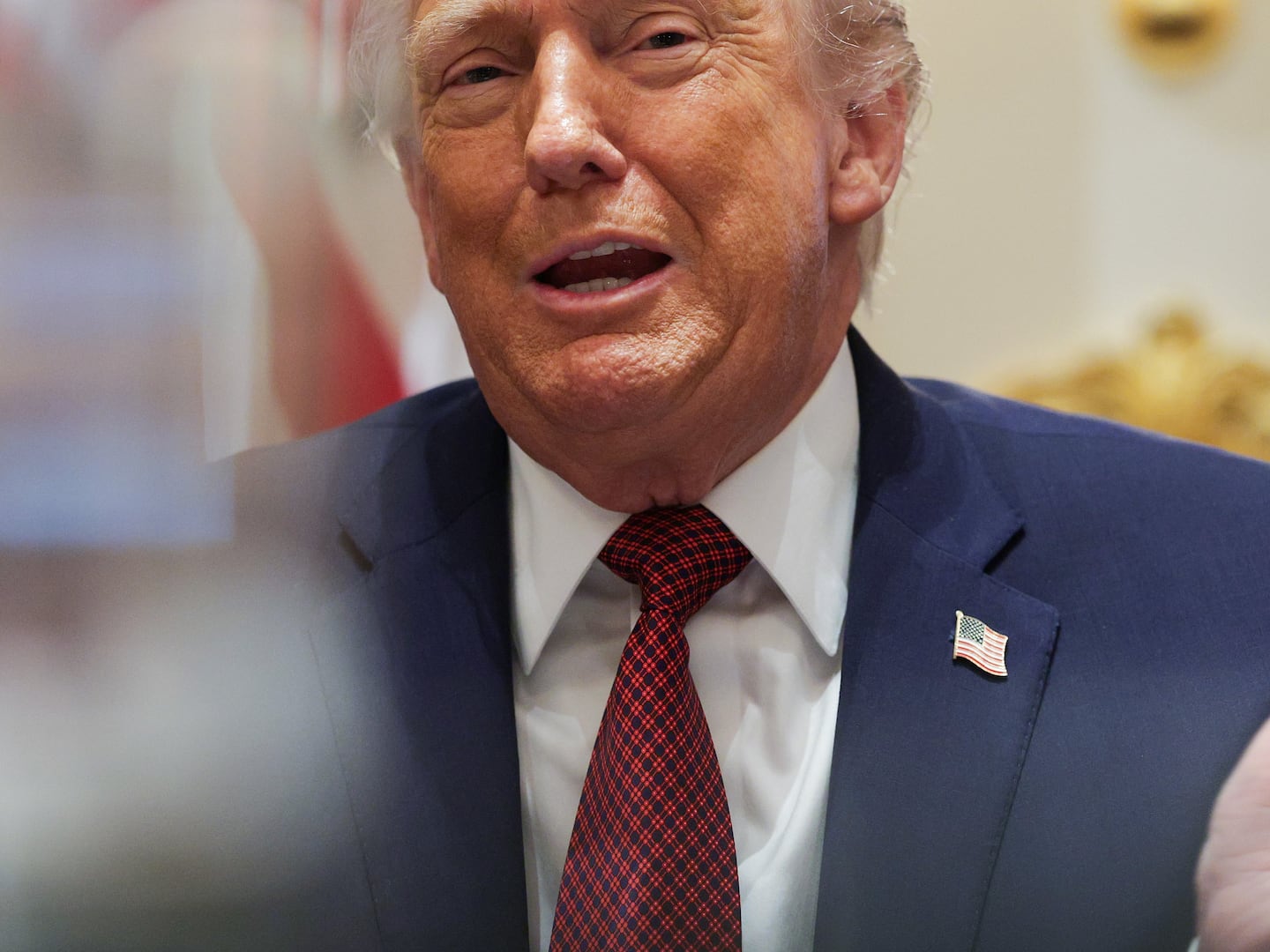

What is clear is that Donald Trump made another of his countless false statements while signing his executive order on police reform on Tuesday.

“President Obama and Vice President Biden never even tried to fix this during their eight-year period,” Trump said. “The reason they didn’t try is they had no idea how to do it.”

This was five years after the task force that included Ghani. But even Obama did not back up his effort with government funding. Ghani has had to continue on by raising funds in the way of academics seeking to do public good.

“We’ll have to figure out the money stuff,” Ghani said on Friday, adding that with regards to staff costs, “Universities don’t pay much, so that makes it easier.”